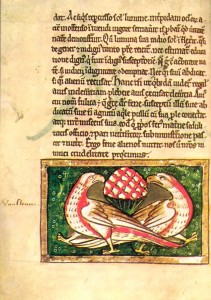

Vulture /vultur/ 10X6.1 cm

Absent in the early versions of “Physiologus”, versions ” Y”, “C” and “B”, the tale of the vulture is based on texts by Isidor /XII.VII.12/ and St.Ambrose /V.20.64; V.23.81/. Like Isidor, the bestiary compilers form the name “vultur” out of “a volatu tardo” which means slow flight. The text describes the bird’s rapacity and acute eyesight. Vultures can see cadavers deep in the sea. According to St.Ambrose female vultures conceive on their own, without males, which prompted a medieval compiler a parallel with the Immaculate Conception of Virgin Mary. The bestiary repeats the ancient legend /Pliny X.6.7/ about vultures following an army and knowing in advance how many soldiers are to die in fighting. Pierre of Beauvais also speaks of the vulture’s ability to foretell a man’s death /11.146/. Philippe de Thaiin and Guillaume le Clerc did not include the chapter about the vulture into their poetical bestiaries, though it is found in the “Bestiary of Love in Verse” /870,3297/ and in writings by Albert the Great /XXIII.I.113/ and Brunetto Latini /I.V.173/. In the original “Physiologus” and in the early Latin version “Y” the story of the vulture includes the story of the eagle-stone which the female vulture would sit upon during her labours. The stone was associated with Virgin Mary. Possibly this legend is a modified version of the antique legend about a horn-stone /lapis aetite/ which the antique writers associated with the eagle /Pliny X.3.4/. “Aviarium” /38/ interprets the acute vision of the vulture who can notice cadavers from far away as a hint at the appearance of the redeemer, who, from the heights of his divinity, condescended to the mortals.