The myth still remains that during World War II Jews were more likely to bemoan their fate than to actively resist the Nazis. This is easily disproved by the 300,000-500,000 Jews that are estimated to have fought in the Red Army.

But due to anti-Semitic policies in the Soviet Union, many of these stories were never told, and today we mostly learn about the Holocaust through stories about the liberation of the concentration camps. In these stories, Jews are massacred until their liberation by the American and Soviet armies.

But since the dissolution of the U.S.S.R. and the opening of long-sealed government archives, we can now see the Holocaust from another point of view: that of the Jewish Red Army soldier and his family living in the Soviet Union.

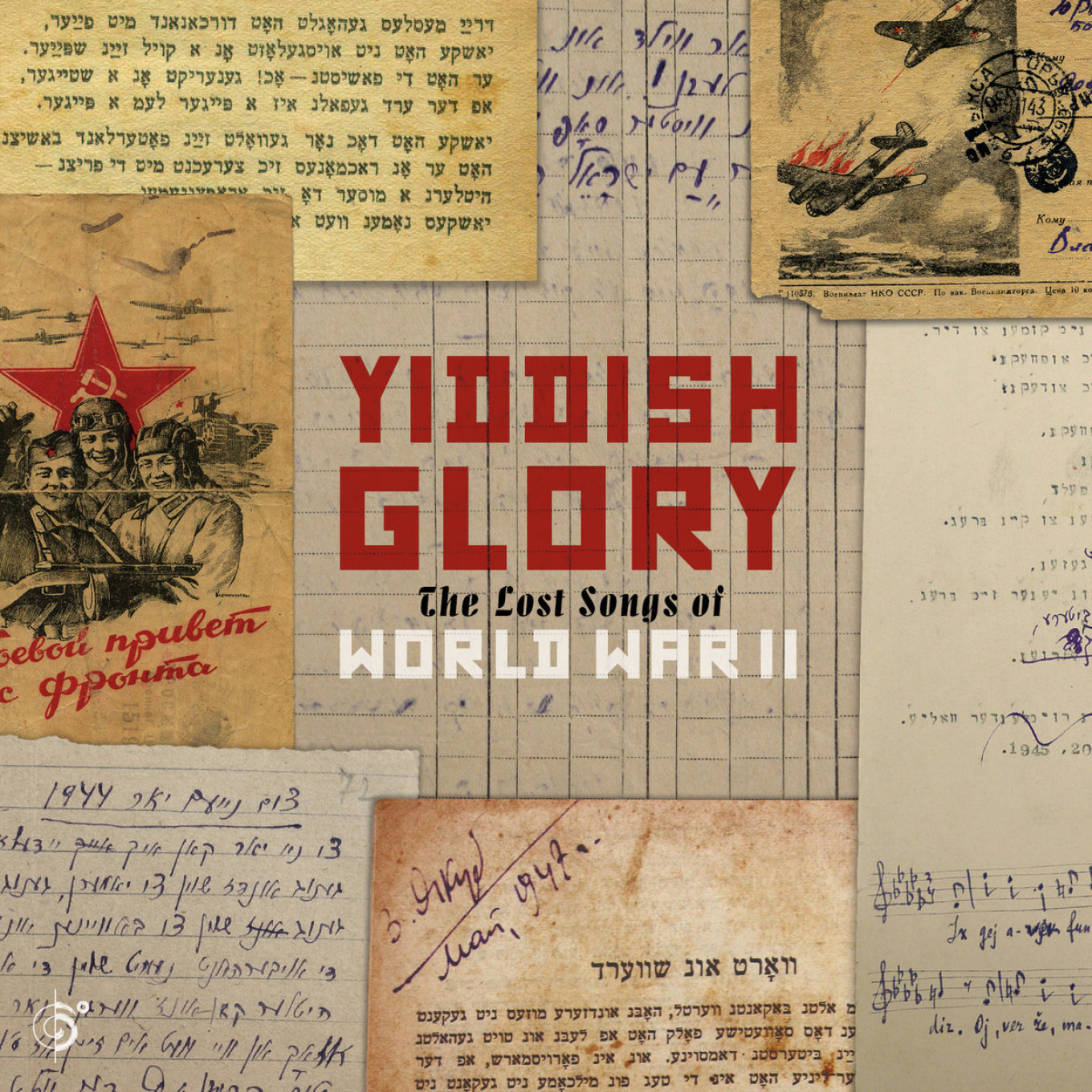

And now there is new material that brings to life a very different story of Jews in what is called in Russia the Great Patriotic War: “Yiddish Glory,” a Grammy-nominated album produced by the University of Toronto professor Anna Shernishis.

Moscow had the privilege of hearing a performance by her and the singer Psoy Korolenko at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center just before the Grammy Awards were held.

Songs lost, then miraculously found

“Yiddish Glory” should have rightfully been made in the middle of the 20th century. The songs, all in Yiddish, were collected by the Soviet ethnomusicologist Moisei Beregovsky during World War II. He traveled through Ukraine collecting Jewish lyrics and tunes from Red Army soldiers and their families for his studies at the Institute of Jewish Proletarian Culture in Kiev.

After the war, while Beregovsky was still working on his project, Josef Stalin, suspicious of Jewish nationalism and the Zionist movement, launched his infamous anti-Jewish campaign. Despite Beregovsky’s efforts to censor the nationalistic elements of the songs, in 1949 his institute was shut down and his work was confiscated. The next year, Beregovsky was arrested and sent to a labor camp, where he would remain until his rehabilitation in 1955.

Although he believed his work had been destroyed, in fact it had remained hidden until Sternishis discovered it in the National Library of Ukraine. Shternishis, whose research focuses on Soviet Jewish culture in World War II, was in Ukraine working on a separate project when one of the librarians mentioned to her that they were cataloguing some Yiddish songs from the Holocaust. Initially she didn’t realize the importance of the find.

“I didn’t want to even read it,” she said in an interview to The Moscow Times, “because, you know, Ukraine, 1944… I could not imagine anything cheerful about it.” But she quickly realized that this was unique, and the first time she’d encountered Yiddish songs from the frontlines of World War II.

The album was nominated for a Grammy. sixdegreesrecords.com

The album was nominated for a Grammy. sixdegreesrecords.comTelling new stories

From a scholarly point of view, these songs present a whole new view of Jewish life during the war. Before finding this material, Shernishis was sure that nothing of the sort could exist. “I wrote a whole book about Jewish life under Stalin,” she said, “and interviewed almost 500 people, of them about 200 veterans. They all told me that even if they spoke Yiddish before the war, they stopped during the war. Nobody sang in Yiddish in the Red Army. So, when 200 people tell you the same thing, you believe them.”

The archives proved them wrong.

Not all the songs are depressing. One mocks recent German defeats in the Caucasus and Donbas, ending with “Hitler is kaput.” Several others are revenge songs, by or for soldiers in the Red Army, promising graphic and pitiless violence for the wrongs committed against the Jewish and Soviet peoples. Yokshe from Odessa, the protagonist of one song, could be the prototype for the “Bear Jew” in Quentin Tarantino’s “Inglourious Basterds.”

But other songs are tragic, documenting specific massacres and concentration camps. What makes these songs so interesting to the average listener and separates them from the enormous quantity of other media concerning the Holocaust, Tarantino excluded, is that they show the Jews as victors, rather than victims. While the songwriters do not shy away from describing tragedy, they also are certain that the Jewish people have been through this before and will defeat this enemy, too.

Singers Isaac Rosenberg and Psoy Korolenko at the Grammies. Dan Rosenberg / MT

Singers Isaac Rosenberg and Psoy Korolenko at the Grammies. Dan Rosenberg / MTRecreating history

Despite the unique story behind the songs, the album would have remained a scholarly curiosity if it had not been for the excellent musicians who brought it to life. The first problem was to create music for songs that were, in most cases, lyrics without any musical notation. “You needed a musician who could do justice to this material,” Shernishis said, “[which is] really amateur, really low-quality text, created in these extraordinary circumstances, in Yiddish.”

Sternishis contacted Psoy Korolenko, a Moscow-based performer, who, she rightly guessed, would be up for the challenge. Korolenko offered to come up with music for the lyrics, and analyzing sources from the time, did his best to match the songs to authentic tunes that would be close the original. In some cases, he proved himself to be a better musician than the people who originally sang these songs. During the Moscow performance, he sang “My Mother’s Grave” in his own version and with the original music, which was discovered after he had already composed his version. While his is haunting and beautiful, the original is grotesque and too comical for such solemn lyrics.

Although “Yiddish Glory” did not win the Grammy, Shternishis was thrilled by nomination. “None of it was expected,” she said. “We see it not as a tribute to us, we see it as a tribute to justice and to Beregovsky, who was so brutally punished for the amazing work he did. His daughter died not knowing about this project. His granddaughters are now seeing all this.”

You can hear some of the music here.