“I was interested in how obsession rises in someone’s life,” the movie director and screenwriter James Gray is saying. “And I wanted to explore that. . .You know, to examine that process.”

Gray is sitting in the cafeteria of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, on Washington D.C.’s National Mall, and talking about his new film, The Lost City of Z, which opens in the United States on April 14.

The film—adapted from a book of the same title by the author David Grann—concerns the British military officer, cartographer and explorer, Percival Fawcett, who disappeared along with his son and a small team in the jungle along the Brazil-Peru border in 1925, while searching for the ruins of a lost Amazonian city he believed to exist.

In fact, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, or at least its early predecessor, was one of the funders of his seventh—and last—expedition into the still uncharted lands of Mato Grosso in Brazil. “You know,” says Melissa Bisagni, “the Museum of the American Indian (founded in 1916 by George Gustav Heye) financed some of Fawcett’s final expedition, but we don’t have anything in the collection because he never made it back!”

Still, the story of Fawcett’s multiple journeys from Britain to South America, and his descent into what became an ultimately deadly obsession is gorgeously documented in Gray’s new film.

The richness of the South American landscapes, the confinements Fawcett felt at home in Great Britain, the increasingly troubled marriage his wife and he endured as Fawcett grew more fascinated by the searching for—and the hope of finding—a lost city in “Amazonia,” are all splendidly portrayed, in both their lushness and the mortal terror that lies just beneath.

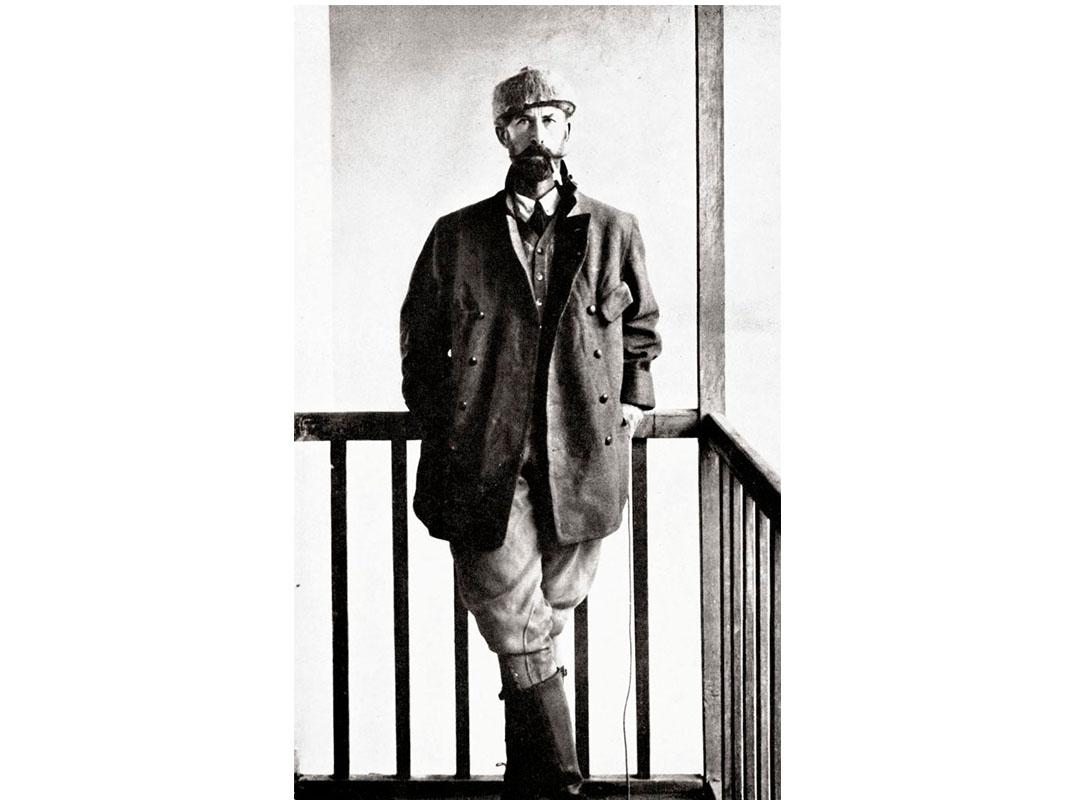

Percival Fawcett, ably portrayed in the film by the actor Charlie Hunnam, is a classic British explorer from the turn of the last century. Born in 1867, Fawcett was educated at the British military college of Woolwich, and afterward did several tours of duty for the British Army and the British Secret Service, in locations as different as North Africa and Sri Lanka. In 1901, like his father before him, Fawcett joined the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), where he studied and learned the craft of surveying and cartography.

In 1906, at the age of 39, Fawcett was sent to South America for the first time by the RGS, to survey and map the frontier between Brazil and Bolivia, setting into motion his fascination with that largely still-uncharted part of the world. By then, he had married and was the father of two, but his extended trips in South America would become the things that defined him. Studying what few written documents there were of that part of the world at the time, Fawcett, in 1913 or so, stumbled onto an account that alleged there was a lost city, the ruins of a formerly great civilization, in the endless and malarial Mato Grosso region of Brazil.

Fawcett was hooked.

The next year, Fawcett, then a largely retired Major with the British Army artillery, would volunteer to serve in World War I, in Flanders, where he was gassed and temporarily lost his eyesight. In 1918, at the end of the war, Fawcett was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and given Britain’s Distinguished Service Order.

“I felt that World War I was the basis of it all,” says the writer and director Gray. “After that, he was a changed man.” Somewhere during the war, Gray says, something heavy had shifted in Fawcett’s life.

Grann’s book gives equal measure to Fawcett’s obsession with his lost city and also the author’s own aversion to the South American trek he knew was required to complete his manuscript. Gray’s film stays keenly on the explorer’s tale. The film is an edge-of-the-seat ride into the wilderness; both internal and external. It’s both beautiful and terrifying.

“I wanted to do a straight Fawcett story,” Gray says. “He was so interesting. After the war, he would sit for hours on end with his head in his hands. And I thought, what happened to him?”

Brad Pitt’s film-production company, Plan B, purchased the rights to Grann’s book and Gray, once signed-on, would soon make his own journey. The film’s South American scenes, shot on-site in Columbia, were demanding, to say the least. And under circumstances that, at minimum, could be called dynamic, Gray had to keep his cast and sizable filming crew together and out of harm’s way.

Gray says he found the experience of shooting in Colombia, “punishing. . . . just punishing.”

During the four-month shoot, eight weeks of which was done in the mountains and river jungles of Colombia, the cast and crew were regularly besieged by nature. “We escaped catastrophe on a few occasions,” Gray says, now smiling as he thinks back on it.

As much of the film’s South American scenes concern either a river journey or a jungle slog (complete with pack animals, who Fawcett sometimes sacrificed for food), getting all of the scenes on-camera regularly proved demanding. Some days, while shooting river scenes where Fawcett and his team are on a bamboo and wood raft, the river would rise and fall eight inches in a matter of minutes, due to unseen cloudbursts upstream, creating torrents that would upset the whole production and drive the cast and crew off the water.

“The river would be your friend, or the river would be your enemy,” Gray says. “It totally depended on the day.”

Another day, during the shoot on land, Gray adds with a smile, an ankle-deep tide of rainwater from somewhere uphill rushed through as they were filming. “You just never knew,” he says.

But during the making of the film, Gray says, he came to understand something about Fawcett that glows through in the film and often creates moments of poetry.

There are shots of thick clouds of butterflies against the blue sunset sky shaded by Amazonian tree canopies, and ominous dark river water that is likely filled with piranhas and black caimans, waiting. There are long shots of mountains, with tiny surveyors—one of which is Fawcett as portrayed by the ropey, intense Hunnam—standing in the foreground, and glimpses through the underbrush of tribal people in loincloths and feathered head-dresses, who are perplexed by these British explorers that have landed in their midst. There are domestic dust-ups between Fawcett and his long-suffering wife, Nina (Sienna Miller) in the British afternoon and evenings, where she no longer knows what to make of her husband and the father of her children. Most terrifyingly, there are scenes where the jungle’s green vegetation erupts in fusillades of native arrows fired at Fawcett and his team.

One shot, in particular, has Fawcett blocking a single arrow fired at his chest using a leather-bound notebook as his shield. It’s a show-stopper.

Also remarkable in the film is the movie star, Robert Pattinson, as Fawcett’s aide-de-camp, Henry Costin, who—with a huge bushy beard and tiny Victorian-age spectacles—is indistinguishable from the teen-heartthrob he played in the “Twilight” series of films beginning a decade ago. As a character in Gray’s film, Pattinson is stalwart and steady. As is Tom Holland, who plays Fawcett’s son, Jack, who was also ultimately lost with his father in the jungles of the upper Amazon, never to be seen again.

The last anyone knows of Fawcett, his son, his son’s best friend, and a few local guides who came to believe Fawcett was unhinged, was at a place that came to be called “Dead Horse Camp,” where Fawcett killed all of their pack animals. Clearly, his guides might not have been wrong about Fawcett’s state of mind.

From there on, the team could only carry what they had on their backs. At Dead Horse Camp, Fawcett sent out a last letter by runner—and that was it. They were never heard from again. A few of the group’s goods were recovered two years later. Teams looked for Fawcett’s remains for a decade.

The story of how they ended up remains a mystery.

Even the native Kalapalo people can’t say precisely what happened to Fawcett in 1925, though the story remains alive with them. It’s said the native people warned Fawcett from going deeper into the jungle, as the tribal people there were not predictable.

Some Kalapalo natives claim Fawcett and his team were clubbed to death deeper in the rainforest. Others say they were killed by arrows. Others say they simply disappeared, lost and eventually mired-down in the forest.

But, as rendered in both Grann’s book and in Gray’s movie, Colonel Percy Fawcett, was now consumed with finding his “Lost City of Z”—no matter if he would ever find it or not. In a pivotal moment in the film, Hunnam screams at those who remain: “There is no turning back!”

It’s terrifying.

Despite the fact that the movie is finished and soon to be in theaters, and at the moment seated in the museum cafeteria on the National Mall, James Gray shakes his head over his plate of lunch as he continues to plumb the mystery that was Lt. Col. Percy Fawcett’s life.

James Gray puts down his silverware. He’s thinking about the mystery that proved the end of Colonel Percy Fawcett, and the journey Gray himself has taken in the making of his movie.

Gray tosses up his hands and smiles.

“Going to the jungle was just safer for him,” he says. “It was safer for him there, right up until it wasn’t.”