In the wake of the Brexit vote and the election of President Trump, the experts and commentators whose ideas shape the ideas of others have tried to pinpoint the cause of the populist fervor that upended many expectations. In op-eds and books (see The Death of Expertise) the consensus seems to be: The egghead is dead.

From This Story

This painful conclusion weighs heavily on public intellectuals, who created the country during the 116 steamy days of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, when Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and crew crafted a new nation entirely out of words. Then they bolstered it with 85 newspaper columns under the pen name Publius, now known as the Federalist Papers, to explain and defend their work.

For a time, it seems, Americans mixed with public intellectuals in their everyday lives. They were our preachers and teachers, discovering their voice in times of crisis. Ralph Waldo Emerson blasted our embrace of slavery, while his fellow clergyman Henry Ward Beecher saved the Union cause by traveling to Europe to deliver a series of riveting speeches that quelled the continent’s desire to recognize the Confederacy.

Intellectualism got a boost after the Second World War, when the G.I. Bill enabled universities to massively increase capacity. In this fertile period, before specialization fully took hold, philosophers, historians and sociologists explained the postwar world to the new hordes of college-educated women and men hungering for mental stimulation.

Television provided a fresh venue. “The Dick Cavett Show,” on ABC, and William F. Buckley Jr.’s “Firing Line,” on public television, launched in the late 1960s, drew heavily from the learned scene. Noam Chomsky joined Buckley to talk “Vietnam and the Intellectuals” in 1969. On Cavett, James Baldwin delineated America’s everyday racism to a Yale philosophy professor. Camille Paglia, Betty Friedan and Arianna Huffington appeared on “Firing Line” as late as the mid-1990s. The topic—“The Women’s Movement Has Been Disastrous”—was pure Buckley, but it was an actual debate, a rare occurrence now that our chat is siloed into Fox News on the right and late-night comedy shows on the left.

It might be that the last great peak was reached in 1978, when People magazine fawned over the essayist Susan Sontag as “America’s prima intellectual assoluta,” noting her 8,000-volume library, her black lizard Lucchese boots and her work habits: “She drinks coffee. Takes speed.” Never before (or since) has an American intellectual had sufficient glamour to grace the checkout aisle.

Only a few years later, in 1985, the Berkeley sociologist Robert Bellah decried that academic specialization had cut our best minds off from the fray. He urged his academic colleagues to engage in “conversation with fellow citizens about matters of common interest.”

The current threat to intellectualism, today’s doomsayers maintain, is precisely that matters of common interest are in such short supply. Through social media, we isolate ourselves in our confirmation bias bubbles, while “computational propaganda” bots on social media, in particular Twitter, stoke this hyperpartisan divide with fake news. You can’t be a truly public intellectual if you speak only to your “in” group.

The information explosion’s impact on intellectual life was brilliantly anticipated in 1968, in a moodily lit television studio, where Norman Mailer and the Canadian seer Marshall McLuhan discussed human identity in an increasingly technological age. McLuhan, in his peculiar Morse code-like cadence, calmly predicted that the media would hurtle humanity back to tribalism. Since we can’t absorb every data point or know so many people well, he explained, we rely on stereotypes. “When you give people too much information, they resort to pattern recognition,” McLuhan said.

Sure enough, in 2017, we are not uninformed; we are over-informed. Scanning our packed feeds, we seek out the trigger topics and views that bolster our perspective.

That’s why we might take a different view of all the fierce arguing online and elsewhere. It is indeed a kind of tribalism, which is marked by a belligerent insistence on cohesion. According to sociologists, humans typically resort to bullying and moral castigation to keep the social unit whole. Maybe our cable-news wars and Facebook scuffles aren’t the death throes of intelligent discourse after all but, rather, signs that this national tribe is furiously attempting to knit itself together.

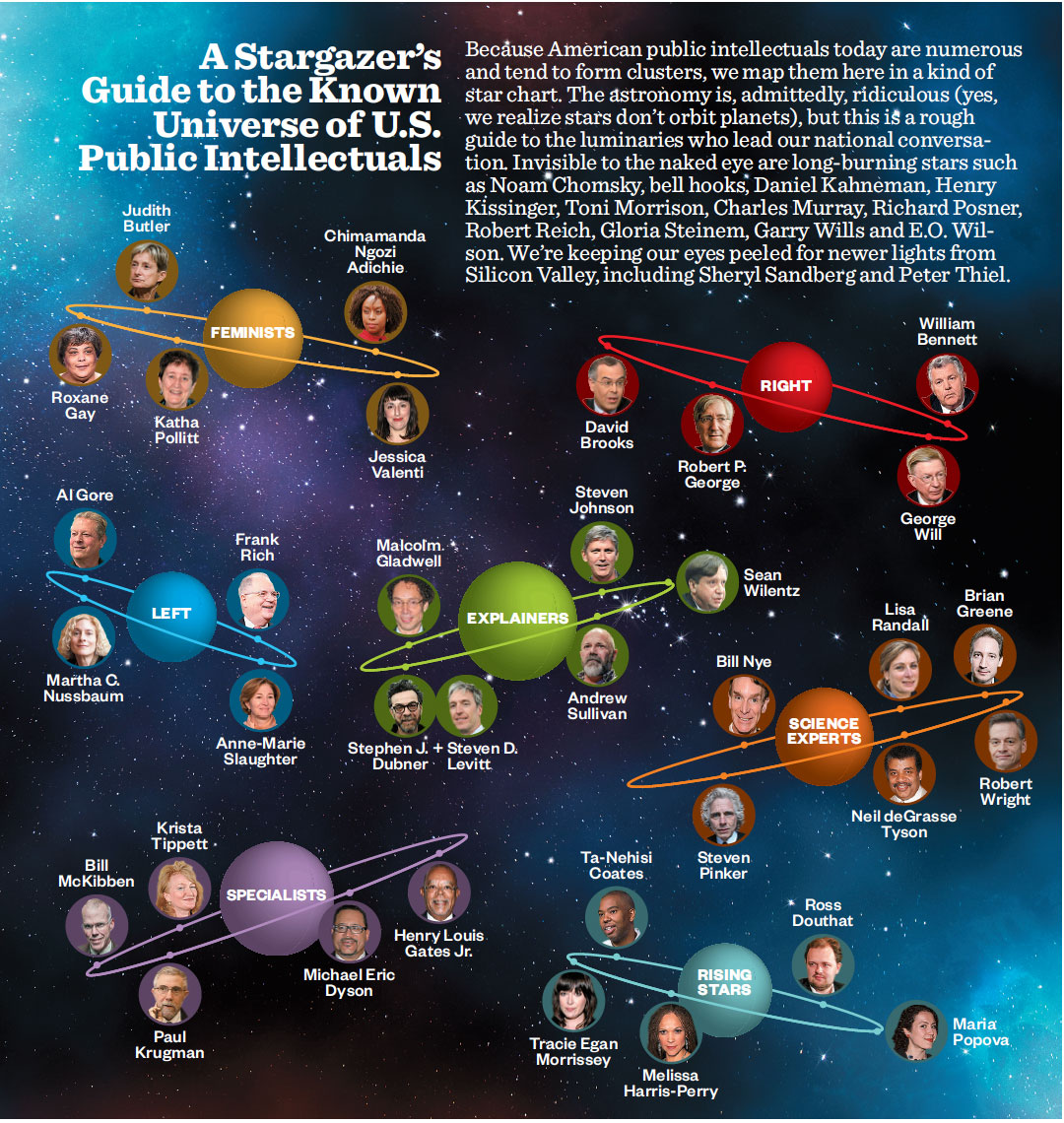

The potential market for intelligent discussion is greater than ever. Over a third of the adult U.S. population holds four-year degrees—an all-time high. And because the number of graduates who are women or African-American or Hispanic has increased dramatically, today’s public intellectuals look different from the old days. It’s no accident that some of our fastest-rising intellectual powerhouses are people of color, such as Ta-Nehisi Coates and Roxane Gay.

If we look back at our history, public intellectuals always emerged when the country was sharply divided: during the Civil War, the Vietnam War, the fights for civil rights and women’s rights. This moment of deep ideological division will likely see the return, right when we need them, of the thinkers and talkers who can bridge the emotional divide. But this time they will likely be holding online forums and stirring up podcasts.

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $12

This article is a selection from the July/August issue of Smithsonian magazine