It was on a sticky Sunday morning in the late summer of 1963 that a bomb detonated beneath the east steps of the historic 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Planted by KKK terrorists, the explosive—a jury-rigged lash-up of 15 sticks of dynamite—ripped instantly through the church’s superstructure, precipitating a cave-in of portions of the nearest walls and filling the interior with asphyxiating dust.

Congregants who had shown up early for the 11:00 a.m. mass, as well as Sunday school students whose morning classes were in progress, evacuated the building in shock and fear. Injuries were numerous. Most horrific of all was the scene downstairs: four young girls who had been in the basement restroom at the time of the explosion—Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley and Addie Mae Collins—were killed by debris. A fifth, Sarah Collins—Addie Mae’s sister—would wind up losing her right eye.

A moment of senseless depravity, the Birmingham bombing, together with the assassination of activist Medgar Evers earlier that year, quickly became emblematic of the deep-seated hatred standing in the way of the African-American crusade for social justice. The events of that fateful Alabama morning lit a fire under many—among them, the ascendant songstress Nina Simone, whose razor-sharp vocals she soon turned to withering social critique.

This tragic inflection point in the Civil Rights Movement served as the inspiration for Nina Simone: Four Women, the latest composition of African-American playwright Christina Ham. Playing at the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. through December 24, Four Women begins its narrative with the discovery of the child casualties of the bomb strike, and quickly turns its attention to the reactions of Nina Simone and three other black women, who, after the dust settles, take refuge in the bombed-out church to avoid the tumult of the streets outside.

Smithsonian.com invited to a November performance of the play curator Dwandalyn Reece, a specialist in music and performing arts at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, home to a number of artifacts from the singer’s career. Reece, a steadfast admirer of Simone’s, was pleased to see the groundbreaking musician depicted onstage. “There was a movement in popular music,” Reece recalls of the mercurial 1960s, “that artists were using to express their concerns, frustrations and anger in so many ways. You think of Sam Cooke and ‘A Change is Gonna Come,’ or Max Roach’s ‘Freedom Now Suite.’ Nina Simone follows in that same tradition.”

The title of the show pays homage to Simone’s composition of the same name; her lyric descriptions of four fictional, archetypal African-American women—Sarah, Sephronia, Sweet Thing and Peaches—form the bases for Ham’s cast of head-butting characters. Over the course of the show, Simone (whom Ham equates with “Peaches”) and her three conversation partners attempt to hash out their identities and arrive at a sense of their place in the larger movement.

Tempers run hot throughout the show, and the dialogue is characterized by a painful cycle of outburst, argument and (fleeting) reconciliation. These four individuals are, after all, very different women: Sarah is a relatively conservative older woman who doesn’t see the use in all the public agitation; Sephronia is an eager activist struggling by virtue of her lighter skin color to earn the trust of her allies; Sweet Thing is a sex worker who services customers of all colors and creeds, and who doesn’t feel as though the movement represents her; and Nina is a free-talking firebrand, looking to infuse her songwriting with the acid welling in her after the bombing.

Punctuating the lively discourse is Nina Simone’s music, which she is constantly tinkering with over the course of the show. Now and again, the various women find it in themselves to smooth over their differences and join together in song. For Reece, these moments of harmony are the highlights of the production.

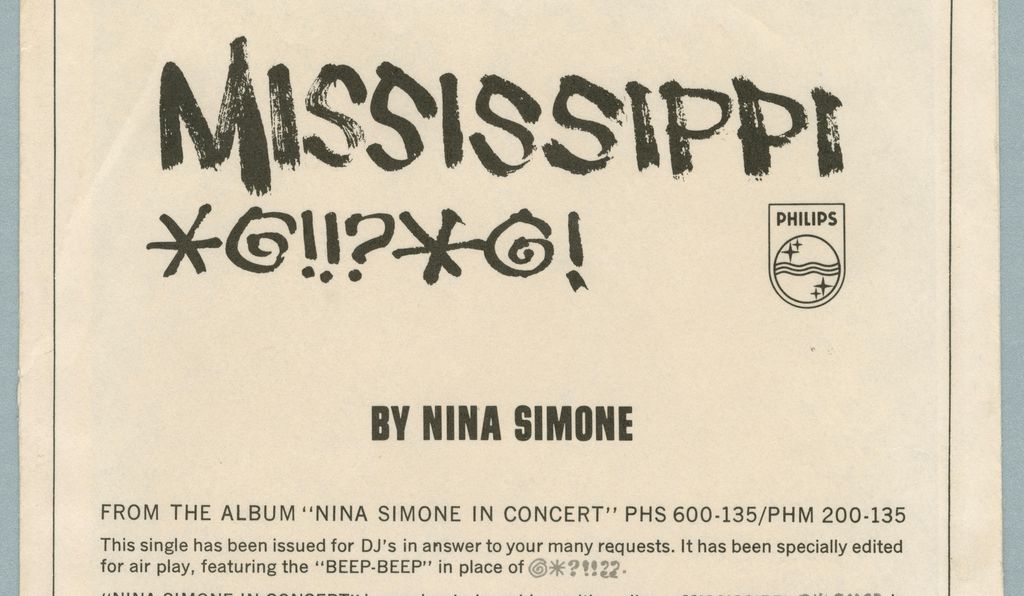

“Having that quartet of singers performing, and the background, the piano—you really get the essence of who Simone was musically,” says Reece. From the inflammatory mock-show tune strains of “Mississippi Goddamn” to the haunting minimalism of the title number, Reece found that the play’s incorporation of Simone’s music succeeded in bringing both her passion and technical virtuosity to life.

Reece contends that Simone’s songwriting was a powerful means of “making bold statements, really expressing her frustration and trying to speak to the cause,” even while taking care not to drown her hopes and aspirations in negativity. “Not only does her music talk about rights and racism and oppression, and the facts of that,” Reece notes, “it also shows a degree of black pride: pride in African-American culture.”

The Nina Simone of Ham’s Four Women is larger than life, full of contradictions and bursting at the seams. For Reece, this messy, all-encompassing vision of the star singer is an apt one, because it allows the playwright to abandon tidy biography of a single individual (an exercise that would be doomed to failure anyway, owing to the constrained timeline of the plot) in favor of creating a transcendent figure for audience members to rally behind.

“It was larger than just Nina Simone herself,” Reece says. “The character is not just a representative of Nina Simone, but of active artists in that time period, who were using their art to speak out to justice and change.”

Through the case study of Nina Simone, Reece suggests, Ham was able to lay bare “the themes and issues that play out, not only in the Civil Rights Movement, but for an African-American woman, of dark skin and musical influences. And how that all affected her.”

The current run of Nina Simone: Four Women at the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. will conclude on December 24.