Since 1932 the building has served as the Odessa Scientists’ Club. Apart from catering to the leisure needs of the scientists it is also the venue of international, national and republican symposia, conferences and seminars. It also houses the Odessa Department of the Ukrainian Society for Friendship and Cultural Ties with Foreign Countries. That is why the address, 4, Mendeleyev Lane is familiar to many foreign visitors.

Mendeleyev Lane leads us to Ulitsa Gogolya (Gogol St.). The three-storey corner building on the left side (21, Ulitsa Gogolya) was built in 1909 by one of the most gifted Odessa architects of the prerevolutionary period, Vikenty Prokhasko. He had an unerring taste and understanding of how to combine the various architectural forms. This building built in the style of the Renaissance palaces makes its impact by the boldness of the patterns of the rusticated facade.

The socle is slightly wider at the bottom. The big rusticated blocks of the ground floor are interspersed by arches, the size of the blocks getting smaller towards the top of the building. The second-storey windows are rectangular, they are decorated with squares and triangular ledges, topped by a protruding cornice. Horizontal lines predominate and only the corner of the building has a traditionally vertical protuberance.

Initially the street was named Nadezhdinskaya, but even before the revolution it was renamed in honour of the great Russian writer Nikolai Gogol, author of The Inspector-General, Dead Souls and many other works now translated into all the European languages. Gogol visited Odessa twice, and on both occasions he stayed in this street. The first visit was in the spring of 1848 when he was returning from Constantinople, he spent several days in house No. 15. Two and a half years later, when illness forced him to leave Moscow in the autumn and move south, he came to Odessa and stayed with a relative, A. Troshchinsky, in house No. 11, and a memorial plaque can be found on this house.

It was in Odessa that Gogol wrote the second part of his Dead Souls, he frequented the theatre and was personally involved in the production of his Inspector-General. He met Lev Pushkin, the brother of the poet Alexander Pushkin, who resided in Odessa, and often visited the Richelieu lyceum. In March, 1851 Gogol moved to St. Petersburg.

Despite the variety of architectural styles on Ulitsa Gogolya nothing mars the overall harmony.

House No. 15, left-hand side, (architects Alexei Shashin and Caetan Dalakva), built in 1846, stands far back from the pavement behind high iron railings. Its neighbour, No. 13, catches the eye by the symmetry of its forms, while No. 11, where Gogol stayed on his second visit to Odessa, was also built by A. Shashin in 1849. The monotony of the smooth facade is softened by the elegant second storey with its bow-shaped windows.

No. 9, a house with sculptural decor on the facade, served for many years, from 1915 to 1941, as the home of the outstanding Soviet eye doctor Academician V. Filatov.

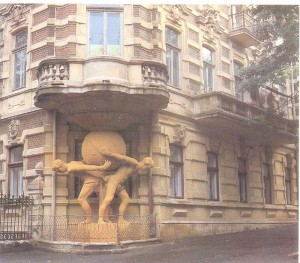

No. 5 and No. 7 stand behind openwork iron railings, revealing a semiclosed courtyard. They were built in the romantic style of the end of the 19th century by Lev Vlodek. The corner bow windows and spired towers create a pleasant silhouette, while the overall stylish impression is reinforced by contrasting colours of the facade. On the corner of one of the buildings are two sculptures of atlantes bent by the weight of the earth they carry on their backs, and these hold up the bow windows of the upper storeys. These buildings rank among the most interesting residential ones of the 19th century.

Two houses on the left side of the street deserve special mention. Four huge stone atlantes on high socles support a wide balcony and seem to stand guard over the entrance and the broad stairway of house No. 6 which was built at the end of the 19th century by architect F. Gonsiorovsky. No. 8, its neighbour, is the oldest in the street and was built in the 1820’s in the Russian empire style, its architect is unknown.

We continue along a side street that branches off in the middle of Ulitsa Gogolya. Like every other street named after an outstanding personality in Odessa the first house on one side of the street bears a tablet with a few words about that person. This street is no exception, the tablet says it was named after the great Russian poet and Democrat Nikolai Nekrasov (1821-1878).

The side street leads to Preobrazhenskaya street formerly Preobraz-henskaya Ulitsa. It is two kilometres long and was originally intended as the main thoroughfare of Odessa. Starting from the slopes near the sea, it cuts the city into its Eastern and Western districts.

From the east the street approaches the coastline at a right angle, and from the west at an acute angle. That is why the corner building on the left-hand side of the street have acute angles, and those on the right, obtuse angles. This is the only street in Odessa with the even numbers on the left-hand side.

As time passed, however, the street lost its significance as the main thoroughfare and merely became an important route linking northern Odessa with the south-western districts.

At the beginning of the street on the right-hand side there is a bronze bust of Marshal Rodion Malinovsky, twice Hero of the Soviet Union, and a native of Odessa (1967, sculptor Yevgeny Vuchetich).

On the corner of Preobrazhenskaya street and Ulitsa Korol-enko (opposite Pereulok Nek-rasova) there is a modest two-storey building (34 Korolenko St.) with a memorial plaque on the facade. It was in this house that the classical author of Bulgarian literature, Ivan Vazov, lived from 1887 to 1889. It was during the Odessa period of his life that he wrote his best known work Under the Yoke.

In the preface to the first edition Vazov wrote: “How home-sick I was for my country… Then inspiration came and I began to write this novel and breathe Bulgarian air.

“It gave me happiness to immerse myself in those dear and unforgettable memories, they inspired me and lent me wings, they breathed new life into my work. From a poor room on a quiet Odessa street, my book has swept through Bulgaria, crossed the borders and flown across Europe. Now I bless this exile.”

In this connection it should be noted that from the very beginning of its existence, Odessa attracted thousands of Bulgarians fleeing from the tyranny of the Ottoman Empire. There are entire villages populated by Bulgarians in the steppes around the city which exist to this day. The descendants of those first settlers retain the language and traditions of their forefathers. After the opening of the Richelieu lyceum in 1817, many Bulgarians travelled to Odessa to get an education. At the beginning of this century Bulgarian revolutionaries, students and workers risked their lives transporting through Varna to Odessa the first Russian national underground Marxist paper Iskra, founded by Lenin and published abroad under his quidance.

After the defeat of the Bulgarian September uprising in 1923 about 1,000 political emigrants arrived in Odessa. At that time the Odessa-Varnaroute again assumed great importance. It was the route along which revolutionary literature published by the Bulgarian emigrants found its way into Bulgaria. All these are striking examples of the longstanding friendship between the peoples of Russia and Bulgaria.

There are several educational establishments on Preobrazhenskaya street. The Institute of the National Economy, founded in 1921 occupies No. 8, a building in the classical style built by F. Gonsiorovsky in the second half of the 19th century. It trains specialists in planning the national economy, in finance, the economics of labour, supply and accounting.

Turning down Preobrazhenskaya street to the left we reach house No. 14/16, the Odessa Art School, the first of its kind in Russia, founded in 1865. Among past students are Mikhail Vrubel, Franz Rubo, Kiriak Kostandi, Yevgeny Kibrik and Mitrofan Grekov. The school now bears the name of M. Grekov, the founder of Soviet battle painting. There are more than 300 students at its three departments, art, sculptural and ceramics.

No. 24 houses a section of the University and, specifically, its science library, one of the oldest in the Ukraine founded in 1817 as part of the Richelieu lyceum. It has 2.5 million books, and of special interest are its collection of rare books and the 25,000 volumes that made up the personal library of the former Governor-Genera! of the Novorossiisk area, Count Mikhail Vorontsov.

The history of Preobrazhenskaya street is very much part of the history of Odessa. The entire working class of Odessa followed the coffin of the Bolshevik sailor, Grigory Vakulenchuk, from the Battleship Potemkin, on the day of his funeral, June 16th, 1905 when it passed along this street. Later in that year, in October, barricades were put up in the street.

In January, 1920, at the police station in house No. 44 Denikin’s henchmen tortured to death a group of members of the Young Communist League working in the underground. Their names are inscribed in gold on the marble memorial plaque on that house.

In 1941 columns of units of people’s volunteers, soldiers and sailors on their way to the front marched down the street.

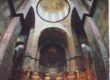

No. 70 on the street is the Assumption Cathedral, built in 1855-1869. Its dome rises to a height of 56 metres.

During the dark days of nazi occupation, a member of the YCL Georgi Dyubakin, hoisted the red flag on the top of the Cathedral (at that time the highest point in the city) on the eve of the anniversary of the October Revolution, November 6th 1943. “Greetings to Our Friends, Death to Our Enemies”, was the message he inscribed in white letters on the flag. Underneath he left a warning; “Minen”, mined, and so the red flag flew over the occupied city all day long bringing hope of early liberation to the hearts of the people.

One block further down Preobrazhenskaya street takes us past the corner of Ulitsa Shchepkina (Shchepkin St.) on the right, which opens with two houses decorated by towers resembling the domes of Russian wooden churches. On the opposite side of the street we turn to the left down Pereulok Mayakovskogo (Mayakovsky Lane). The eminent Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930) loved Odessa and visited it four times. During his first visit in 1914 he fell in love with a local girl, Maria Deni-sova, but his love was unrequited. Nevertheless it served as the basis for his well-known poem “A Cloud in Pants”.

House No. 6 on this street served for many years as the home of the composer and conductor Jifi Pribik, People’s Artist of the Ukraine, a Czech by nationality. From 1894 to 1937 he was the musical director of the Odessa Opera.

His neighbour in No. 4 during 1920-21 was Vasili Blyukher, hero of the Civil War and an eminent Soviet military commander.

Turning to the right from Pereulok Mayakovskogo we find ourselves on Ulitsa Khalturina. It is named after Stepan Khalturin (1857-1882), a revolutionary worker, and one of the organisers of the North-Russian Worker’s Union, the revolutionary organisation of the St. Petersburg working class.

Together with Nikolai Zhelvakov, Khalturin organised the attempt on the life of the military governor of South Russia Strelnikov, who was notorious for his brutality.

No. 4 on Ulitsa Khalturina, built in 1876 by the architect F. Gonsiorovsky, today houses the Department of History of the Odessa Museum of History and Regional Studies.

The Museum illustrates the history of the Black Sea coastal area from the 14th century to our times, with the special emphasis on the struggle of the Russian and Ukrainian people against invaders, for their freedom and independence. Old weapons and other exhibits tell the tale of Russia’s wars against the Ottoman Empire, about the great Russian military leaders Alexander Suvorov and Mikhail Kutuzov, and of one of the founders of the Black Sea Fleet Admiral Fyodor Ushakov. Many of the exhibits refer to the Ukraine’s national-liberation war against the Polish magnates (1648-1654), and the historic reunion of the Ukraine and Russia (1654). There is also a section on the Crimean War (1853-1856), while special sections illustrate Odessa’s freedom-loving and revolutionary traditions. The section dealing with the Great Patriotic War (1941-45) shows the city’s war production during its heroic defence, tropheys captured in battle, the banners of the military units that liberated the city, and the weapons and personal belongings of the heroes of the defence and liberation of Odessa.

From Ulitsa Khalturina we turn to the left and continue along Ulitsa Lastochkina (Lastochkin St.). We passed the beginning of the street when we followed the first route. Ulitsa Lastochkina is one of the few in Odessa with almost no trees. Its greenery is supplied by the grape vines decorating the houses on the sunny side of the street.

The walls of many of the houses in Odessa are covered by decorative vines, and frequently one can see clusters of “Isabella” or “Lydia” grapes at a height of the third or fourth storeys. In August to September many people in Odessa bring in a crop of grapes grown on their own balconies and make their own juice or wine.

In House No. 24 there is the department of the Museum of History and Regional Studies which deals exclusively with the history of the “Philiki Eteria”, the secret society of Greek patriots founded in Odessa in 1814, which played a major role in preparing the Greek uprising against the Turks.

Each street in Odessa is lined with its own species of trees. Thus Ulitsa Karla Marksa which we reach by turning to the left, is lined with chestnut and catalpa trees. In the spring the candle-like rose-white flowers turn the street into a place of beauty, and in the autumn few passersby can resist picking up the shiny chestnuts, which seem to have accumulated the warmth of the past summer.

Odessa, in general, is a very green city, but not only because of the abundance of trees, bushes and flowers on its street and in its parks. Practically every courtyard has its own little garden of acacia and chestnut trees, planes and linden, cherry, plum and apple trees.

Catherine Street was given its present name in the first years of Soviet power to commemorate the founder of scientific communism, who mentioned the city many times in his letters and works. Odessa was one of the first cities in Russia where Russian translations of Capital and The Communist Manifesto first appeared and were circulated. It was in Odessa that “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law. Introduction” was first published in the translation of Vatslav Vorovsky. However, it was not only the progressive forces in Odessa that were interested in Marx’s works, so were the police who worked hard to confiscate his books. There was one incident when they proved to be over-zealous. At the end of 1871, the Odessa police were warned by the authorities in St. Petersburg that the chairman of the German section of the International, Marx, was planning to visit Russia for nefarious purposes with a British passport. In May 1872, on a ship that arrived from Constantinople, the police found a man named Marx. He held a British passport although German by nationality. The police were taken aback by his boldness as he had made no attempt to change his name. He was listed among the passengers as Julius Alexander Maria Marx. Although the man protested that he was a merchant from Nottingham who had come to Odessa on business, the police kept him in strict custody for several days. When at last the misunderstanding was resolved, the authorities had to reimburse the merchant for lost time.

Catherine street is one of the central streets. At the beginning of the street there are a number of monumental buildings with marble stairways, mosaic and sculpture decor, and towers and arrow-like Gothic windows. Before the revolution they were the homes of the cream of local society, the gentry, the bankers and senior civil servants.

Today there are many offices on st. Catherine in addition to dwelling houses. For instance, the headquarters of the Antarctic whaling fleet Ukraina occupy house No. 17.

Under the master plan for the development of Odessa, the section running from the coast up to Ulitsa Deribasovskaya (Deribasov St.), between Ulitsa Pushkinskaya and st. Catherine, will be kept intact as a special preservation zone. No modern buildings will be allowed, and viewing platforms will be arranged.

Turning to the left and walking down st. Catherine for another block we reach Ploshchad Potemkintsev from which we started.