Women’s figure skating is one of the most eagerly watched events of any Winter Olympics, with reliably high American viewership numbers at the events of the past 30 years. Just like famous skaters such as Michelle Kwan, Dorothy Hamill and Peggy Fleming before them, this year’s female soloists hitting the ice in PyeongChang will be part of a long line of women figure skaters who made their names in competition.

With its costumes, its routines and its tradition of musical accompaniment, from the perspective of 2018 it probably doesn’t seem surprising that figure skating is the oldest women’s Winter Olympics sport. Together with six traditional summer sports including tennis, sailing, archery and croquet, it was one of the first sports with a category for women competitors–and the only women’s winter Olympic sport until 1936. What might be more surprising to many is that figure skating was originally considered a totally masculine pastime, says skating historian James R. Hines.

Of course, women (like men) have been skating, as a means of transport or recreation, for about as long as ice skates have been around. The first modern ice skates with metal blades date back to the Middle Ages and were made by the Dutch, though there’s evidence that humans were using animal bones to skate across ice several millennia before that. In a demonstration of women’s place on the ice, the Catholic Church’s patron saint of figure skating, Saint Lidwina, was a Dutch teenager from the late 1300s who fell and broke her leg while skating on one of the many canals.

The first figure skating competitions took place in the mid-1800s, during a period where skating became more popular and local skating clubs formed throughout Britain to give interested parties a chance to show off their skills. One of these skills was the ability to skate “figures”–literally pictures on the ice. Generally, Hines says, these interested parties were men, but most clubs had no hard prohibition against women competing. Women skaters could do “figures” just as well as men could, despite the obvious hindrance of heavy skirts, he says. It wasn’t as fast-paced as today’s figure skating, but skating images into the ice required skill and precision. In the first-know figure skating manual, published in the 1770s, author Robert Jones devotes a full page to describing how to properly perform a maneuver known as the “Flying Mercury” that leaves a spiral in the ice, and another to showing how to “cut the Figure of a Heart on one Leg.” Although figure skating became more athletic, it retained a tie to this early practice of making figures well into the 20th century.

Although the four plates in Jones’s book all show men in various skating poses, Hines says the popular masculine image of a figure skater didn’t preclude women from trying out the moves. In the late 18th century, when skating clubs began to form around England and Scotland (the first formed in Edinburgh in the 1740s), the idea of “figure skating” became more formal and local clubs started hosting competitions. According to Hines, it was certainly possible for women to compete at some local clubs, showing off their ability to do “compulsory figures” with descriptive names such as the “circle eight,” “serpentine” or the “change three.”

Still, there was no significant tradition of women competing. Over the course of the 19th century, as local skating clubs started competing with one another in national skating associations and then an international governing body, “they just presumed women wouldn’t compete,” Hines says. But women, as it turned out, had other ideas.

The International Skating Union (ISU), which still oversees international skating competition, was formed in 1892 and hosted the first World Figure Skating Championships in 1896: just four men competed in the event. Then in 1902, a woman, British figure skater Madge Syers, entered the competition thanks to a loophole in the rules; there was no rule disallowing women, wrote Hines in the Historical Dictionary of Figure Skating.

Syers placed second in that competition, behind Swedish skater Ulrich Salchow, whose last name now describes the skating move he was famous for: a simple jump and midair spin. Salchow offered Syers his gold medal, saying he thought she should have won.

The WFSC closed the loophole soon after and barred women from competing in the Worlds. Their purported reason: concern that long skirts prevented the judges from seeing the potential onslaught of female competitors’ feet. The ISU then created a specific competition for women only, the Ladies World Championship. It still exists today, meaning no woman can call herself the World Figure Skating Champion without engendering a few “well, actually” rejoinders.

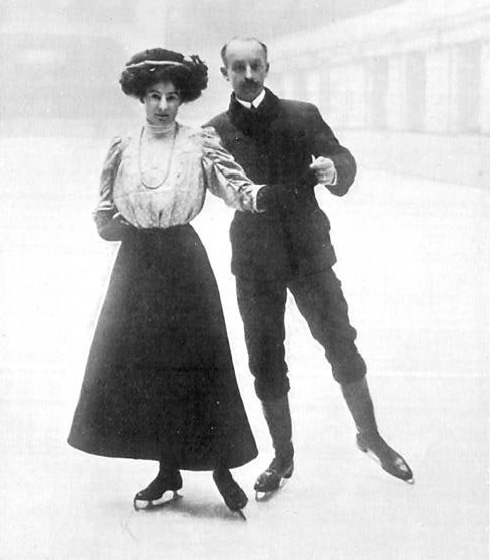

The objection to Syers’s skirt was just the start of female competitors’ wardrobe woes. When American Theresa Weld added the Salchow to her repertoire at the 1920 Olympics, she earned a reprimand. Why? As Ellyn Kestnbaum writes in Culture on Ice: Figure Skating & Cultural Meaning, “because her skirt would fly up to her knees, creating an image deemed too risqué.” But in spite of criticisms like these, women quickly took their place as competitors in the sport. In 1908, Syers co-authored The Book of Winter Sports with her husband, also a competitive figure skater. In the chapter titled “Skating for Ladies,” she wrote that “skating is an exercise particularly appropriate for women.”

She argued for their place in competition by drawing on traditionally “feminine” virtues, writing “it requires not so much strength as grace, combined with a fine balance, and the ability to move the feet rapidly.” International skating competitions were also “the sole instances in which women are permitted to contend in sport on an equality with men.” They may not have been able to earn credit for being world champions, but at least women could compete solo on the ice and be professionally judged.

Over time, the clothes worn by those skaters who arrived after Syers and Weld shifted from ankle-length skirts to higher skirts that allowed more freedom of movement. At the same time, figure skating had become less a technical pursuit involving the tracing of figures and more an artistic pastime involving costume, moves taken from dance, and athletic feats. With this growing recognition came the inclusion of figure skating in the 1908 London Olympics, with competitions for both men and women (Syers took gold.) At the first Winter Olympics, held in 1924, figure skating was the only event with a women’s category. By that time, Syers had died, but Austrian Herma Szabo took gold, the first of many women to win at the Winter Olympics.