The pink has returned to George Washington’s cheeks. The dress sword in his hand glistens anew. There are now buttons, and a kind of shape to the black suit that was once a murky blob.

And what’s that in the background, a rainbow?

The 18-month restoration of Gilbert Stuart’s famous 1796 full length portrait of a 64-year-old George Washington is the centerpiece of the reopening of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery’s “America’s Presidents” in Washington, D.C.

The iconic 8-by-5-foot work is known as the Lansdowne portrait, after its longtime owner, England’s Marquis of Lansdowne for whom it was commissioned by U.S. Senator William Bingham. It was a gift to thank him for his role in negotiations that led to the Jay Treaty that put an end to the Revolutionary War.

Ironic that it hung in England for more than 170 years before it came to the Smithsonian museum in 1968, at first on long-term loan before it was acquired with a gift from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation in 2001.

It’s been greeting more than 1.2 million visitors annually at the museum’s permanent “America’s Presidents” exhibition until it closed in early 2016.

The outstretched hand of the nation’s first President is meant to be in a classic oratorical stance, but seems to be beckoning viewers to the renovated and refurbished gallery of presidents, as if to say, “Come on in! Learn something about Rutherford B. Hayes!”

There are 146 portraits of George Washington in Portrait Gallery holdings, including an iconic unfinished one by Stuart that also hangs among the presidents.

But it is the Lansdowne that alone shows him standing for the first time in nonmilitary garb, as a citizen, at the end of his presidency. An iconic pose for Stuart, there were a number of replicas of it that still hang prominently at the Old State House in Hartford, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Museum, the Brooklyn and the White House.

The latter is the version that was famously rescued by Dolley Madison when the White House burned in the War of 1812 (Stuart distinguished copies by misspelling the titles on the volumes that lean against a table leg).

For the National Portrait Gallery’s head of conservation Cindy Lou Molnar, who spent 18 months restoring the painting, the toughest part was the coat, which had become little more than an oblique shape.

“There was some problems with previous cleanings but there was also a lot of old varnish left on the black coat,” Molnar said, “so it was very thick and it made the coat look more like a silhouette than an actual coat.”

Mostly, though, Molnar said that “taking off that thick varnish certainly showed the brilliance of the painting. It showed fresh new details under the surface, and it made it much cooler too. It was like lifting off a yellow veil.”

Though it hadn’t quite disappeared, the portrait’s surprising rainbow, meant to represent a hopeful future for the young country, had been obscured by the yellowing varnish.

“Natural resin varnish was something they used a lot in the past, which is fine, except when it’s exposed to the atmosphere it does have a tendency to oxidize and turn very yellow. So, it really influences the look of the painting after a period of time,” Molnar said.

And on the Lansdowne, she said, “for some reason the overall tone was so much of a yellow tone, you didn’t notice those beautiful differences that existed in the surface.”

The rainbow’s intensity reappears boldly not only in the painting’s upper right hand corner but in the middle of the painting, between a couple of Doric columns.

Washington may not appear to be the full 6-foot-3 of his actual height (there was a body double posing), but other parts of the painting delight, from the details on the eagle-carving on a table leg to the highlights on a silver inkwell featuring the Washington coat of arms, amid a table top arrangement that includes a white quill pen and a black hat.

“It’s such an interesting area of the painting,” says Molnar, “but when we cleaned it, it was like wow.”

Because the Lansdowne was such a large painting she couldn’t restore it on an easel. “I had to clean it on a cart,” she said. “I had the painting on its side, I had it upright. I had ladders.”

She also spent a lot of her time testing the painting to see exactly what kinds of varnishes and previous restorations she was dealing with. Ultraviolet light-induced visible fluorescence gave some clues in that field, but infrared reflectography failed to find underdrawings or other clues to preliminary sketching.

There was some thought that Philadelphia architect Samuel Blodgett may have assisted in the design of the chair, the table leg and the books, as was indicated in a letter written in 1858. But there was no evidence from the digital X-rays.

“What we did find with the infrared was that Stuart did take paint to the brush and used that quite well in outlining and doing a lot of compositional images,” Molnar said. “He didn’t use pencil or chalk to do underdrawing.”

For its reopening, the popular America’s Presidents exhibition has been re-contextualized, relit and rewired such that there are electronic kiosks from which a wide variety of information can be gleaned on the art, its subjects, and history at the time. Each portrait description is also in Spanish for the first time.

The National Portrait Gallery is the only place other than the White House with portraits of all the U.S. presidents. The museum began commissioning portraits in the early 1990s, following the end of the George H. W. Bush administration; and a few on display are on loan.

By tradition, a portrait is not commissioned until a president’s term is over, so there is no portrait of Donald or Melania Trump.

The one major portrait of Trump in the National Portrait Gallery is a 1989 photograph by Michael O’Brien of the real estate mogul tossing an apple. It also served as cover of Trump’s 1990 book, Trump: Surviving at the Top. The photo was last on view around the time of the inauguration January 13 to February 27.

The official portrait of Barack and Michelle Obama will be formally installed in early 2018, tying in with the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Portrait Gallery. Until then, a couple of 2013 black and white photographs by Chuck Close of the 44th president are standing in.

Close was also the painter behind the nearly impressionistic portrait of Bill Clinton in the gallery that, at 9-by-7 feet, is even larger than the Lansdowne Washington.

Close’s portrait of Clinton is on loan to the Portrait Gallery; the painting of the 42nd President that was commissioned by the Portrait Gallery was removed from public view in 2009, six years before the artist pointed out that he had slyly included the shadow of Monica Lewinsky’s infamous dress in it.

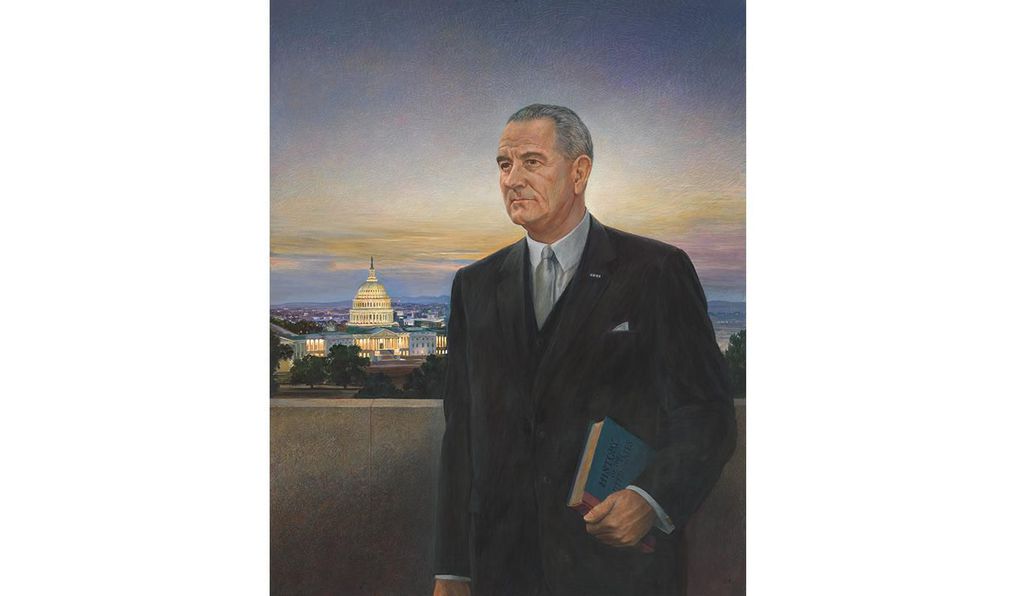

Other presidents have been outspoken about their distaste for their portraits. The one commissioned by the White House of Lyndon Johnson was rejected by LBJ who called it “the ugliest thing I ever saw.” The artist, Peter Hurd, then gifted it to the National Portrait Gallery when it opened in 1968, but the museum promised not to show it until Johnson left office.

“America’s Presidents” continues indefinitely at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.