For practically a century after its founding, the United States still couldn’t lay claim to any distinct cuisine. The emergent nation generally relied on a meat, potatoes and cheese diet, with fruits and vegetables often left off the dinner plate. Moreover, commonly held wisdom said that too many spices or condiments might just ruin one’s moral character; plain, boring graham crackers were the cure for sexual urges. All the better, then, to keep the palate plain and food flavorless.

But starting in the 1870s, America began to shift towards seasoning and cultivating a better understanding of nutrition. There was a willingness to try new foods, including the exotic banana that debuted at the 1876 World’s Fair in Philadelphia, and to try new ways of preparing the mainstays.

The timing was ripe for adventurer and botanist David Fairchild, born in East Lansing, Michigan, on the cusp of this expanding gastronomic era. More than a century ago, starting in the 1890s, Fairchild worked for the United States Department of Agriculture, journeying around the world to send back seeds or cuttings of over 200,000 kinds of fruits, vegetable and grains. His department, the Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction, researched and distributed new crops to farmers around the states.

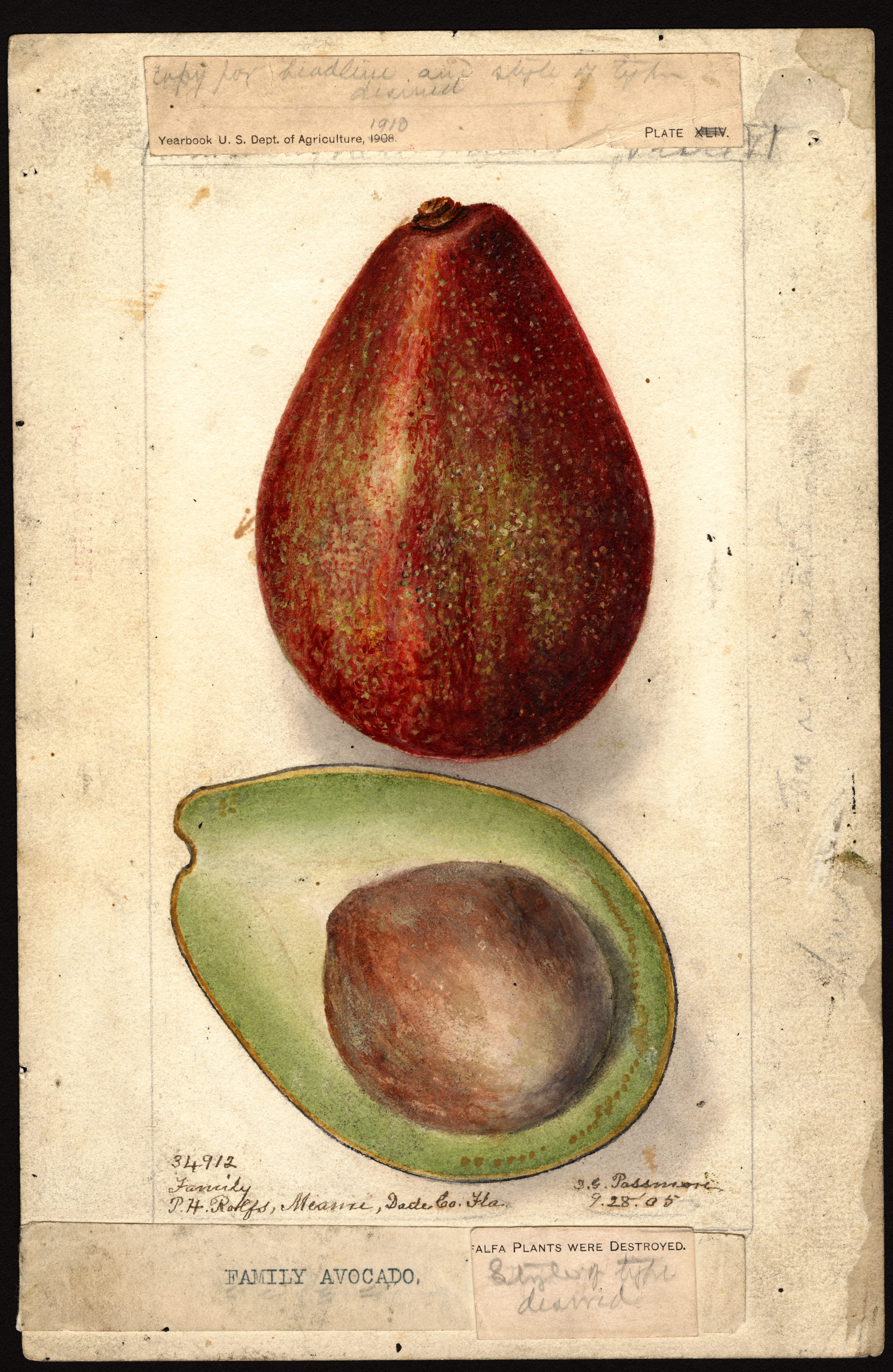

So the next time you devour an overpriced slice of avocado toast, munch on some kale or serve yourself some quinoa, you’re sampling just a few of the crops that Fairchild introduced to the American public. A new book, The Food Explorer, offers a look at his journeys around the world and how he changed the American diet. Author Daniel Stone, a writer for National Geographic, spoke with Smithsonian.com.

So who was David Fairchild?

David Fairchild was an adventurer-botanist, which is a title that has rarely existed in history. He was a man who grew up in Kansas, at a time when the United States was very blank. It was in need of a lot of growth. Economic growth, military growth and culinary growth. And he detected an appetite for all of those types of change, which led him to conduct world-wide adventures at a time when not that many people traveled. He went to places that not that many people went, in search of foods and crops that would enrich farmers and very much delight American eaters.

Where did Fairchild’s fascination with plants come from?

He grew up in parts of Michigan and Kansas. His father, George Fairchild, was the first president of Michigan State University, and then the first president of Kansas State University. As a result of living in both places, Fairchild had access to the plains to farms, farmers, and people growing things. He saw up close that there wasn’t a lot of dynamic crops in those days, not a lot of variation.

You had a lot of corn, you had a lot of potatoes. There were some apples, tomatoes. Very much American-centric crops. But when you think of what’s in our supermarkets today, in terms of bananas and mangoes, and pears and pineapples, these are things that all came from abroad. And in large part were brought here by Fairchild, and people who came after him.

Where did he travel? Who was facilitating his journeys?

His first trip was to Naples, Italy, funded by a grant from the Smithsonian. And on that trip, he met a very wealthy underwriter, named Barbour Lathrop. It was literally on the ship from Washington to Italy. He met this fabulously wealthy man, who he ended up partnering with in pursuit of exploration. And this man, Barbour Lathrop, underwrote many of his travels.

For about five years he traveled with Lathrop, on Lathrop’s dime. Eventually this project was sponsored and absorbed by the United States government. So Fairchild went from kind of an independent agent to a government employee and became very much a government food spy in his role. As sanctioned by the Secretary of Agriculture, and the President of the United States [from William McKinley’s administration until Woodrow Wilson’s], his job was to find exotic crops and bring them back.

Sometimes it was diplomatic and friendly. And sometimes it was covert, and he would steal things.

What was so high-stakes about what he was doing?

At that time in America, in the late 19th century, 60-70 percent of the labor force were farmers. Farming was the main industry, the main economic engine of the United States, and of much of the world. It was really the currency that made economies rise or fall.

For example, America was in the beer making business in those days, but not in a big way. Beer making was very much the domain of Europe, and specifically Germany. And so Fairchild had an assignment to go to Bavaria in Germany, to acquire hops—some of the best hops in the world. And when he gets there, he realizes that Germany knows that it has the best hops in the world, and it doesn’t want anyone to get them. Or to acquire them in a way that could create a rival industry, a competitor somewhere else in the world.

The Food Explorer: The True Adventures of the Globe-Trotting Botanist Who Transformed What America Eats

The true adventures of David Fairchild, a late-nineteenth-century food explorer who traveled the globe and introduced diverse crops like avocados, mangoes, seedless grapes–and thousands more–to the American plate.

In Germany in those days, the hops growers hired young men to sit in the fields at night and essentially guard their crop from being stolen. Fairchild gets there, and essentially has to befriend a lot of these men, so they would trust him. It was still covert, and he didn’t have to steal them, but he did eventually acquire the hops that he brought back to the United States. And that really ballooned the hops industry, here in America.

What effect did his missions have?

If Fairchild hadn’t traveled to expand the American diet, our supermarkets would look a lot different. You certainly wouldn’t have kale (which he picked up in Austria-Hungary) to the extent that you do today. Or food like quinoa from Peru, which was introduced back then, but took off a century later. Anyone who’s eaten an avocado from Central America or citrus from Asia can trace those foods back to his efforts. Those fruits hadn’t permeated American agriculture until Fairchild and the USDA created a system to distribute seeds, cuttings and growing tips. Fairchild went to great lengths, at times risking his life, to find truly novel crops, like Egyptian cotton and dates from Iraq.

He started this tradition of food exploration, with other explorers following his lead. How long did the position stay in place?

This program lasted from about the mid-1890s to the start of World War I in 1917. And the reason for that coincides with that chapter in American history. So you can imagine the era of Teddy Roosevelt coming to Washington at the dawn of the 20th century. The growing aspiration of the United States. And that all coincided with getting things from around the world that could be useful to America.

The U.S. did that with colonies like Puerto Rico and the Philippines. And it did it with crops also. Now, the reason it stopped, is because when World War I started, you also have the dawn of a sort of nationalism. A sort of nativism, that is similar in ways to what we see today, where we don’t want things from other parts of the world, because some of them [seem to] threaten our way of life, our way of existence.

Food was a part of that. And so you had a growing number of people in the United States at that time saying, “We don’t want these plants, we don’t want these crops from all over the world to enter our borders, because we don’t know what they’re going to bring in the way of diseases or insects or fungi.”

That growing [nativist] faction led to a passing of a quarantine law in after World War I, that essentially required all plants coming into the U.S. to be searched and tested before they were distributed. And that slowed down the work of Fairchild and his team a lot, until it finally ended. That quarantine law, by the way, is the reason that when you get on an airplane now, from abroad, you have to fill out that form that says, “I’ve not been on a farm. I’m not bringing in agricultural material.”

Before it used to be totally legal to do that, which Fairchild benefited from. But after, you could see how that would just slow down the work of importing thousands of exotic plants from around the world.

How did the farmers feel about the new crops Fairchild was sending over? And how were the seeds and cuttings being distributed?

Even Fairchild would say that the process of food introduction was very difficult. It’s a giant question mark, because you don’t know what farmers are going to want to grow. Farmers don’t like taking risks. The business has traditionally very small margins, so people who take risks generally don’t find them to pay off. But some crops farmers liked to grow.

[Imported] cotton in the American Southwest was a good example. But Fairchild would bring some things back, and if you couldn’t create a market for them, farmers wouldn’t want to grow them. And if you couldn’t get farmers to grow them, you couldn’t create a market for them. So, it was a challenge to get some of these items infused in the American agriculture scene, and then in the American diet.

Fairchild helped facilitate the planting of D.C.’s Japanese Cherry Blossom trees, but it almost didn’t work out.

Fairchild went to over 50 countries, but he was in Japan around the turn of the 20th century. He saw the flowering cherry trees. And when he got back to Washington, he learned there was an effort already under way to bring cherry trees to Washington. This was being undertaken by a woman at the time named Eliza Scidmore.

Fairchild added a lot of push to that effort because he was a government employee; he was a man of high status and had married into the family of Alexander Graham Bell. But Fairchild essentially arranged a shipment of those trees to his house in Chevy Chase, Maryland, where people would come see them. People loved them. Eventually he secured a shipment for the Tidal Basin in D.C.

Japanese officials were so touched by his interest, and America’s interest, that they sent extremely large trees with long roots, which they thought would have the best chance of flowering very quickly.

But the trees showed up, and they had insects. They had fungi. They were diseased. And it was a big problem, because you don’t want to import insects from the other side of the world, that could demolish any part of American flora. So, as a result, the President William Taft ordered the trees burned, which could have caused a great diplomatic crisis. Everyone was concerned about insulting the Japanese. The Japanese were very good sports about it, and they agreed to send a second shipment.

That shipment was much better, younger trees, with their roots cut much shorter. And it arrived in pristine condition. They were planted in a very non-descript ceremony, in part by David Fairchild, down on the mall in 1912.

What was Fairchild’s favorite food discovery?

His favorite is called the mangosteen, which is unrelated to the mango. It is, in fact, a small fruit that’s purple and about the size of your fist, or maybe a little smaller. And inside it’s kind of like a lychee. It’s got white flesh that’s really slimy and really sweet. So you would essentially pull the purple rind off, and you eat the flesh in the middle. There’s not much of it, but it is delicious.

He always thought it was the best of all fruits. He called it the queen of fruits. And he thought that Americans would love it. He tried repeatedly to introduce it, but as a result of it only growing in tropical climates—he found it on the Indonesian island of Java—and a result of it being a lot of work to grow, for not that much fruit inside. never really caught on.

And I’ve thought a lot about why. Compare it to a fruit like an apple, which ships and refrigerates very easily, and there’s a lot of fruit there. Or a banana that has a rind to protect it. Or an orange that can be grown in a couple of climates around the U.S. and be shipped long distances. The mangosteen was not really suited for any of those. It had kind of a weak resume, so it never caught on, and he regretted that for decades.

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $12

This article is a selection from the January/February issue of Smithsonian magazine