“This artwork is an act of international terrorism.”

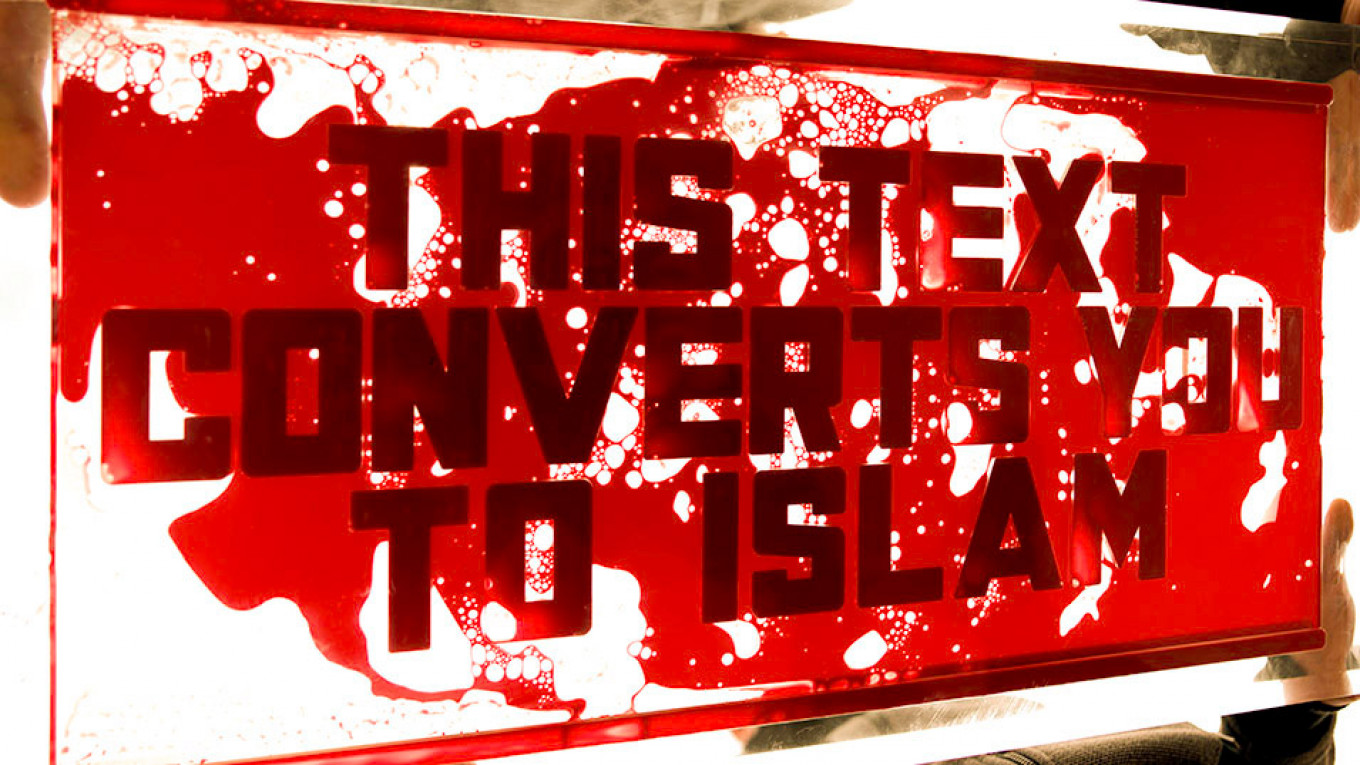

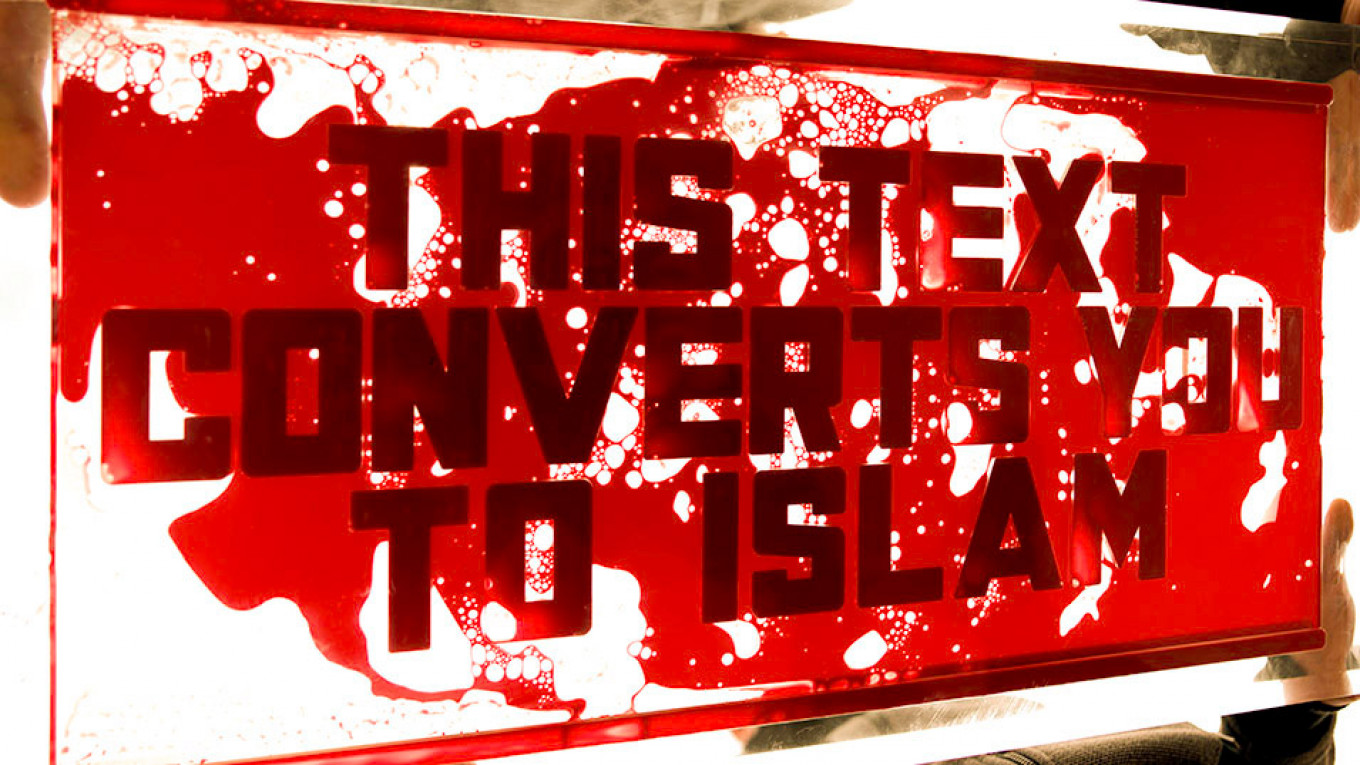

“This text converts you to Islam.”

“This artwork makes you want to hijack an airplane.”

Russian artist Andrei Molodkin’s newest exhibition shouts out these statements in loud, bold, blood-red letters. And the blood comes from real humans.

Opening at Dublin’s Rua Red art space on Valentine’s Day, “Bloodline” confronts the language used by law enforcement around the world to silence voices of dissent.

Born and raised in the Soviet Union, Molodkin was exposed to this language of power from an early age and heard it even more during his two years in the Soviet Army. Today, he resides in France — but says he increasingly hears echoes of this language in the world around him.

“Before the Soviet Union collapsed, we experienced censorship. I now find the same issue slowly coming back in every country,” he told The Moscow Times.

“[The courts] try to get an expert to explain why a work of literature, poetry or music is dangerous to society. For instance in Russia they might say ‘Your artwork incites people to harm the Russian president,’ or ‘This work engages in hate speech against the administration’ or ‘This work provokes destruction of government or religious symbols.’”

Each of the pieces in “Bloodline” is created from a transparent plexiglass form. It’s impossible to read the sentences when the plexiglass is empty. The words only become visible when blood starts circulating through them. A medical pump circulates the blood through each sentence at a rhythm that imitates a human heartbeat.

Molodkin first got the idea to use blood as an artistic tool when he served in the Soviet Army and saw a fellow soldier shoot himself in the heart.

“One of my friends, who was very creative and free, had a hard time — the military tried to break him to turn him into a great soldier, and under this pressure he shot himself in the heart. The people in charge dragged him 30 or 40 meters along the road. When we were crossing the base, we saw a huge red line on the road. Nobody could cross it because we were so scared and in such shock. That shock stayed with everyone who saw it. I believe this was his last artistic gesture in this world.”

It’s not the first time Molodkin has used human blood as his preferred medium. In 2009, he drew controversy with “Le Rouge et le Noir,” which pumped the blood of a Russian veteran of the Chechen War through acrylic replicas of the Nike of Samothrace standing atop blocks filled with Chechen oil. “Catholic Blood,” his 2013 installation in the Northern Irish city of Derry, tapped in to the sectarian strife that continues to draw dividing lines in the city.

Viewers will even be able to donate their own blood to his latest art piece, with qualified nurses on hand to administer the donations. When they do, they’ll be “participating in the mechanism of power language and thus becoming part of the installation as artists,” Molodkin said.

“I believe that everyone with blood flowing in their body is an artist, because whenever you accidentally cut yourself and blood drips on your robe or on the table, you are marked or get an image from it,” he said.

“Bloodline” runs from Feb. 14 to March 27 at Rua Red in Dublin. More information here.