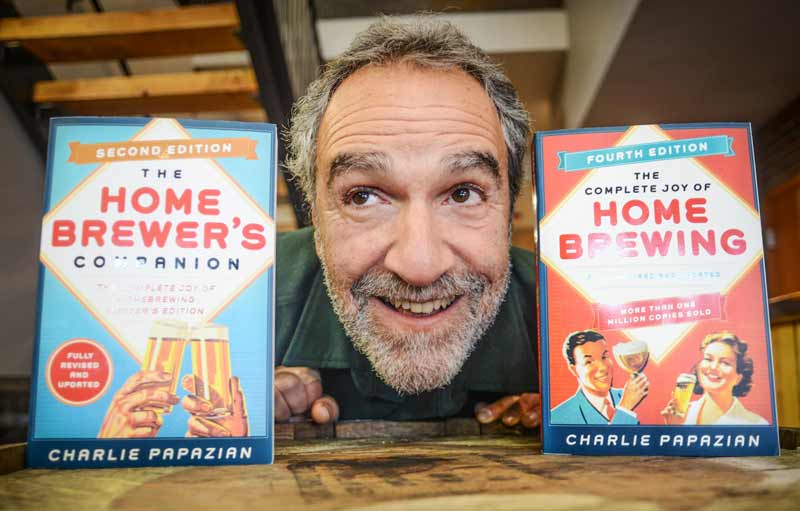

In 1984, Charlie Papazian authored The Complete Joy of Homebrewing, a landmark text (now in its fourth edition) that laid out for the first time in simple, straightforward terms, the basic formula for making beer in the comfort of one’s home.

Papazian soon became the guardian of an entire generation of brewers and his calming mantra, “Relax, Don’t Worry, Have a Homebrew,” set the cultural stage for beer to become more than just a beverage in modern America, but a way of life. The last few decades have witnessed the number of breweries in the United States jump–or rather, skyrocket–from a meager 100 the year his book was published to just over 5000, as reported last spring by the Brewer’s Association (an organization Papazian himself helped found).

But while nothing jostles one’s beard hairs like a freshly poured Northern California IPA, this barley-based beverage had to travel a long way before it became the drink of choice for tatted, plaid-wearing urbanites across the nation. The oldest proto-beers trace back, not to Europe and our colonial forefathers, but to the Fertile Crescent, and one of the first known written mentions of it in the 4th century BCE come from the travel diary of the ancient Greek mercenary, Xenophon, as he wandered across what was then, quite coincidentally, Papazian’s ancestral homeland: Armenia.

Though ethnicity has never been a motivating factor in Papazian’s beer obsession, one must admit, it is rather serendipitous. And even more so now that the very movement he’s helped spearhead in America, filled with DIY microbreweries and brewpubs, has finally made its way full circle. As remarkable as it sounds, Armenia might just be both one of the oldest and one of the youngest nations in the history of beer making.

Certainly, much has transpired since Xenophon sipped on that strange barley concoction in the Armenian highlands over two thousand years ago, but unfortunately for beer, the well-documented history of wine in the region usually takes center-stage. The little we know about Armenia’s historic brewing habits unfolds primarily within the last two hundred years and, like most ‘then-and-now’ type stories in former Soviet countries, it is defined by the rise and fall of that peculiar Russian breed of socialism we call the U.S.S.R.

In the late-19th century, when we start to see the first mentions of beer factories in Armenia, beer was emerging as a lucrative industry in the Russian Empire. Factories were opened in Alexandrapol (now Gyumri) and Kars, areas which had historically inherited European brewing techniques from medieval monks and which were also well-disposed to growing local ingredients, like barley. While Kars is no longer part of modern-day Armenia, the beer factory in Gyumri still exists and though it operates out of a newer building, the historic factory from 1898 has been preserved and curious, beer history buffs visiting the area can take tours.

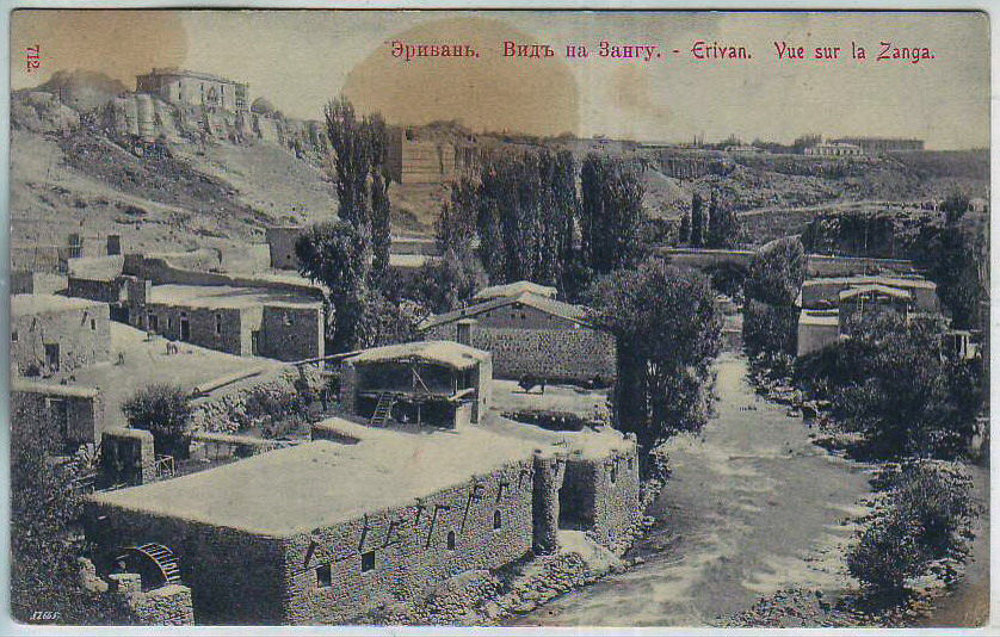

In Yerevan, the most famous factory was Zanga Brewery, located in the picturesque Hrazdan River Gorge. Founded in 1892 by Harutyun Avedyants, the son of a successful factory owner. Zanga produced only one style of beer, a traditional German Bock. For a while, business was good and the brand achieved some international success, both across the Russian Empire and in Europe (even winning some awards in Naples and Milan).

In 1917, Lenin’s communists seized power and all major factories were nationalized. When Armenia became an S.S.R., Avedyants, like many other successful entrepreneurs, lost his business. Without the specialized expertise required for beer production, however, the business began to go under. So, on March 1st, 1924, in a sobering twist of fate, Avedyants was hired as an employee of the very factory he had founded over thirty years earlier. After his death in 1926, the factory closed and there would not be beer production in Armenia again until after World War II.

These were the dark ages for beer in the U.S.S.R. Alcoholism was a huge problem affecting worker productivity, so the state began actively discouraging alcohol consumption. When beer making finally did return to Armenia in the 1950s, it did so with few innovations. Picking up where they left off, beers made in the traditional German pilsner style, popular in the Russian Empire, came to dominate industry. That, combined with anti-drinking propaganda, resulted in an extremely homogeneous market in which any variety from outside the Iron Curtain had to be procured through an underground black market.

A network of subversive beer drinkers emerged, gathering in Soviet Armenia’s watering holes. The good stuff was possible to find – for the right price – if you had the right acquaintances. Novelist Gurgen Khanjyan recalls these days nostalgically, “The old Yerevan beer lovers were not small in numbers… We used to talk about everything, but there was a sense that an invisible eye was watching us. The beer lover of an independent country is different. He enjoys beer differently, freely… unafraid, uninhibited…”

So while Americans in the 1980s were busy heeding the calming mantra of Charlie Papazian (“Relax, Don’t Worry, Have a Homebrew!”) and opening their hearts and minds to the endless possibilities being created by the growing craft beer movement, Soviet citizens were scuttering through dimly lit alleys, risking their freedoms for a highly-coveted lager from nearby Czech Republic.

Naturally, a more liberal market brought about by the fall of the Soviet Union and Armenia’s independence has done wonders for the alcohol industry in Armenia. According to a report from 2015, consumption in 2014 was 24.5 million liters of beer – a figure which is up 32% from 2010. But while these numbers sound promising, 80% of beer consumed in Armenia is produced by only a handful of mainstream breweries who offer a generic product, which is affordable, but deviates little from the pilsners of Soviet times.

Fortunately, 2012 signified the beginning of a cultural shift with the opening of several new beer-oriented establishments in the city. “Back then, there was a stereotype that breweries were mostly places for men,” observes founder Armen Ghazaryan, founder of one of Armenia’s first craft brewpubs, Beer Academy, “So from the very first day we focused on being a family place.” Ghazaryan’s establishment has evolved from an uncertain novelty to a successful business with a loyal following from locals of all ages.

But craft beer as a concerted cultural movement in Armenia didn’t take off until the spring of 2016 with the launch of Dargett. Founded by two brothers, Aren and Hovhannes Durgarian, Dargett is a brewpub that has embarked on countless firsts since it opened: the first IPA made on Armenian soil, the first cider made from Armenian apples, the first fruit beer in Armenia (a lovely ale infused with Armenia’s most abundant and symbolic fruit: apricot). Everything they touch turns to ‘first’.

The variety Dargett’s founders strive for is impressive, even for longtime veterans of brewing; around twenty styles are rotating on tap at any given point, all of which have been crafted on site in the restaurant’s downstairs dining area where behemoth, steel tanks transported from Italy last year are visible to diners behind large panes of glass. “I’m sure they [mainstream brewers in Armenia] think we’re naïve lunatics,” says Aren Durgarian, “Because why brew in variety when they’re selling millions of just one style?”

But despite this skepticism, Dargett and Beer Academy have both evolved into highly successful businesses with plans for expansion, even while serving what might arguably be the world’s most affordable craft beer at less than $2 a pop. “We need to be able to reach young people who may not have access to this product if it were too expensive,” the Durgarians explain, “We want them to test our beer, since the youth is the main component in any cultural revolution.”

The price is all the more surprising since starting a brewery in a country like Armenia is a very expensive and risky undertaking. Unlike brewers in the U.S., with access to developed supply chains and expedited shipping models, the Durgarians say they must order their ingredients from abroad at least a year in advance. A local supply chain, while not out of the question, just isn’t realistic right now.

But what is an Armenian beer if it’s made with all foreign ingredients? And what did Xenophon’s mysterious barley drink of yesteryear taste like? One can only hope that consumers’ growing curiosity will someday soon provide the incentive for answering these questions.