When the National Portrait Gallery first opened in Washington, D.C. 50 years ago with a small collection, two other countries sent loans. “One was England,” says Robyn Asleson, assistant curator of drawings and media arts. “The other was Switzerland.”

So, when the museum embarked on a new exhibition series called “Portraits of the World”—to feature one international work a year and surround it with works from the museum’s collections that broaden its context—it knew which country to feature first.

Back in 1968, Switzerland had lent five 19th-century portraits of American sitters from Walt Whitman to Civil War generals by the Swiss artist Frank Buscher. But when it decided on Switzerland to be the inaugural country in Portraits of the World, “it had to be Hodler.”

Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918) was the revered national painter of Switzerland who was also “interested in a lot of the issues of identity and nationality that intrigue us at the Portrait Gallery,” Asleson says.

What’s more, showing his work would coincide with the centenary of the artist’s death. “The only problem was that museums all over Europe were also interested in Hodler in 2018 and organizing their own exhibitions,” Asleson says.

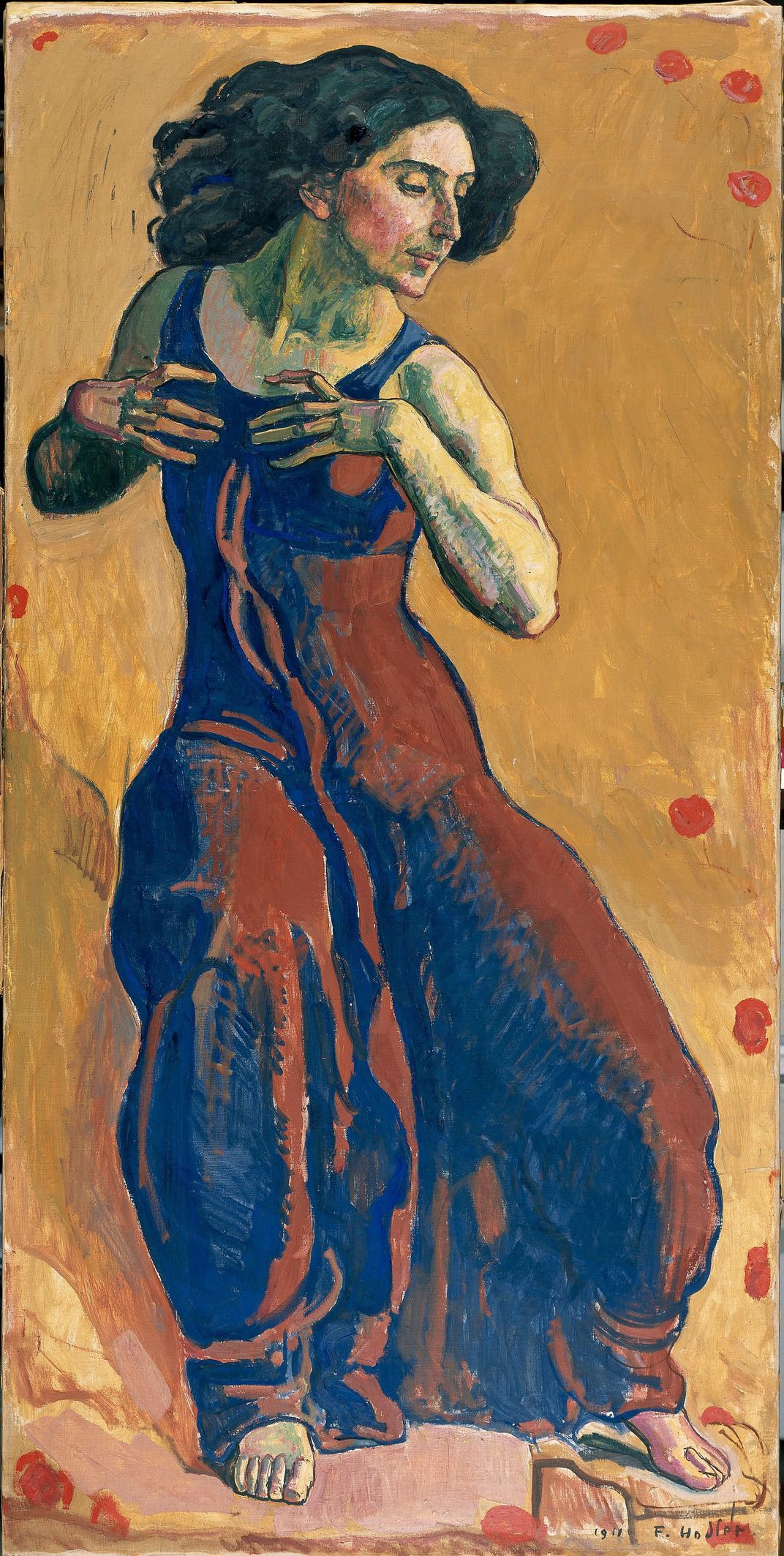

But with the help of the Swiss embassy here, it obtained a particularly vibrant work, Femme en Extase (Woman in Ecstasy), a 1911 portrait of the Italian dancer Giulia Leonardi, on loan from the Museum of Art and History in Geneva. To complement the loan, the museum has selected a collection of figures who helped create modern dance at the turn of the last century, back before it even had that name.

With its vibrant color and brush work and its depiction of motion, Femme en Extase “really speaks of Hodler’s interest in movement and emotion and how the challenge of representing emotion in a static form and through dance,” Asleson says.

It is also reflective of the work by his friend Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, founder of a theory called Eurhythmics, a way to study music through movement and rhythms. The practice is still taught in schools (and its name was later borrowed by a 1980s rock group).

The swirl of the dancer’s movement in Hodler’s work “may not look very ecstatic, but when you think of women at the turn of the century who were very corseted and tightly-bound and had very strict rules of decorum, here you have this beautiful Italian dancer moving with incredible freedom. That would have been seen as quite a liberated way of behaving at that time,” says Asleson.

Using a similar kind of untrained and unbridled movement used in Eurhythmics were dancers like the Americans Loïe Fuller, who created an innovative style of dance that involved hundreds of yards of fabric, iridescent color and the spectacle of turning into a flower or bird on stage. Her movements are captured in a large 1897 chromolithograph for the Folies Bergère by Jules Cheret.

Fuller, a former burlesque dancer in America who was celebrated in Paris, took another American ex-pat free dancer Isadora Duncan under her voluminous wing and led her to international fame as well. Duncan is represented by a drawing made while she was freely dancing and in a 1916 photograph by Arnold Genthe also wearing loose Greek drapery.

“The ideas of what dance should be were very traditional and she was interested in a kind of free dance, as opposed to ballet, so instead of corsets and tutus and point shoes and very strict movements, she just wanted to move her body freely—and do it barefoot,” Asleson says.

Indeed, she adds, the form was called barefoot dancing and free dancing before it became known as modern dance. “She believed the way forward for modern dance was by going back to antiquity and imitating the way the body moved, the poses and drapery,” Asleson says of Duncan, who famously met her fate in a 1927 car mishap. “At the same time, it seemed so daringly modern for a woman to be wearing so little clothing and to be comporting herself with so much abandon. It was one of those paradoxes of being both modern and antique at the same time.”

Someone deeply influenced by Duncan was the Japanese-born American Michio Itō, who was in Paris to learn opera. “He saw Isadora Duncan perform and was so overwhelmed that he decided he would become a dancer instead of a singer,” Asleson says. “He went to study Dalcroz Eurhythmics, as did Isadora Duncan at that time.” He is depicted in a striking 1921 photograph by Nickolas Muray.

It was Itō who introduced Isamu Noguchi to Martha Graham, the influential American dancer and choreographer who had studied Eurhythmics while at the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts in Los Angeles, which had been founded by Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis. All three are represented in the exhibit.

Among the events planned in conjunction with the Portraits of the World: Switzerland exhibit is a performance by the Portrait Gallery’s choreographer in residence, Dana Tai Soon Burgess that will revive some of the historical dances of Itō and others.

It’s all inspired by the central work by Hodler, who may not be as well known in America as he is in Europe, possibly because the Impressionists took all the attention at the time, Asleson says.

Besides, Hodler was “not making art easy for you,” she says. “He was very interested in symbolism so a lot of his paintings are about life, death, love—a lot of his big allegories that he painted.

Rather than concentrating on fussy pointillism, “he has a very rough expressionistic brush work he uses to convey a sense of vitality and vigor and strength, going back to the Swiss ideals of healthiness.”

Having a choreographer-in-residence and a number of works depicting modern dance in the collection may have helped the Portrait Gallery attain the work at a time when the works of Hodler are especially in demand in Europe.

Portrait Gallery Director Kim Sajet says “this modest but extraordinary exhibition coincides with major Hodler retrospectives in Switzerland, Germany and Austria, all of which are commemorating the centennial of the artist’s death.”

But Asleson says that it helped that Martin Dahinden, the Ambassador of Switzerland to the United States and his wife Anita, chair of the museum’s Diplomatic Cabinet, got involved.

The Portrait Gallery’s choice of Hodler, Dahinden says, “shows how much we both value our longstanding relationship, which spans back to the museum’s opening. We place such collaborations at the core of our diplomatic work as they allow us to build bridges to our host country and its culture, to nurture synergies and to understand each other even better.”

“Portraits of the World: Switzerland” continues through November 12, 2018, at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.