Perhaps denoting their eight years in the White House as a singular moment in time, the official portraits of Barack Obama and Michelle Obama unveiled at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery Monday, seem to float in time and space as well.

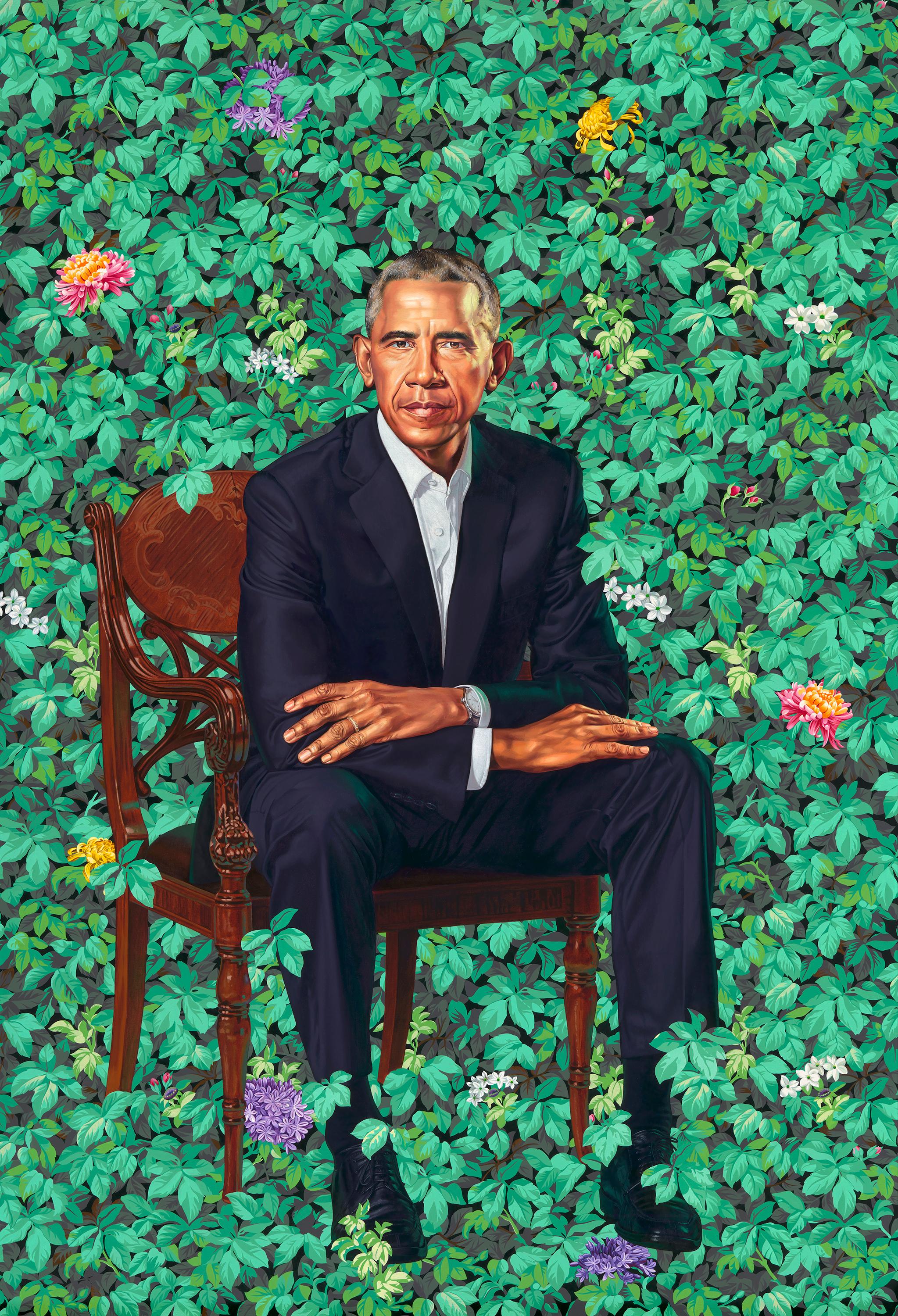

Obama, in a vibrant 7-by-5-foot portrait by Kehinde Wiley, sits with an intent, direct gaze, surrounded by encroaching greenery punctuated with specifically chosen flowers. Michelle Obama, baring her famous arms, sits in her 6-by-5 foot portrait by Amy Sherald in flowing dress with aspects of a patchwork quilt, floating in a background of robin’s egg blue.

“Wow,” said Michelle Obama at the museum unveiling. “It’s amazing.”

“Not bad,” said the 44th President of his own likeness. “Pretty sharp.”

Of the two artists, personally chosen by the Obamas, through a process guided by the Portrait Gallery, Wiley may be the best known, for his grand portraits that put ordinary African-Americans in heroic poses typical of Renaissance portraiture, surrounded by vivid, colorful patterns.

With these ordinary subjects, who the artist met on the streets, “Kehinde lifted them up and gave them a platform and said they belong at the center of American life,” Obama said.

“That was something that moved me deeply,” Obama said. “Because in my small way that’s what I believe politics should be about—Not simply celebrating the high and the mighty, expecting that the country unfolds from the top down, but rather it comes from the bottom.”

In his case though, Obama said he didn’t want to be pictured in horseback or with a scepter. “I had to explain: ‘I’ve got enough political problems without you making me look like Napoleon,’” he joked. “‘You might want to bring it down just a touch.’ And that’s what he did.”

Sitting in a wooden chair, his face serious if not grim, it’s clear the portrait came from the end of his presidency.

“I tried to negotiate less gray hair,” Obama said in jest. “And Kehinde’s artistic integrity would not allow him to do what I asked. I tried to negotiate smaller ears—struck out on that as well.” Overall, he said, Wiley, “in the tradition of a lot of great artists,“ listened to the former president’s ideas—“before doing exactly what he intended to do.”

Both men said they were struck by parallels in their life stories. “Both of us had American mothers who raised us, with extraordinary love and support,” Obama said. “Both of us had fathers who had been absent from our lives.”

And while the subject of his painting is not rendered in as heroic a style as he’s done in the past, Wiley’s love for florid background did come to the fore.

“There are botanicals going on there that are a nod to his personal story,” Wiley says. Poking through the profusion of green are the chrysanthemum, the official flower of the City of Chicago, jasmine from Hawaii where Obama spent his childhood; and blue lilies for Kenya, where his father hailed.

“In a very symbolic way, what I’m doing is charting his path on earth though those plants,” Wiley says.

Visually, “there’s a fight going on between him and the plants in the foreground that are trying to announce themselves,” Wiley says. “Who gets to be the star of the show? The story or the man who inhabits the story?”

Growing up as a kid in South Central Los Angeles and going to museums in L.A., Wiley says “there weren’t too many people who happened to look like me on those walls.”

Part of his work has been to “correcting some of that—trying to make places where people who happen to look like me do feel accepted or do have the ability to express their state of grace on the grand narrative scale of a museum space.”

This grandiosity is done with the simplest of tools. In his case he thanked his mother—a single mother like Obama’s. “We didn’t have much but she found a way to get paint,” he said between tears. “And the ability to be able to picture something bigger than that piece of South Central L.A. that we were living in.”

It was done with the simplest of tools, he said.

“It seems silly—it’s colored paste, it’s a hairy stick; you’re nudging things into being. But it’s not. This is consequential. It’s who we as a society decide to celebrate. This is our humanity. This is our ability to say: I matter, I was here.

And for him, “the ability to be the first African-American painter to paint the first African-American President of the United States,” he says. “It doesn’t get any better than that.”

There is every reason to believe the Obamas knew of the work of both artists before they were chosen to paint the official portraits which will hang with the Gilbert Stuarts and the Elaine deKooning in the “America’s Presidents” gallery.

“They really did make an effort to put African-American artists in the White House,” says Portrait Gallery director Kim Sajet. And the family often toured the museum after hours, where Sherald was the first woman to win the gallery’s Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition in 2016.

“Kehinde and Amy are taking the best of portraiture traditions and adding a fresh layer by absorbing the influence of fashion, music, hip hop, pop culture and painterly inventiveness,” Sajet said at the ceremony. “Together they are transmitting the energy of urban America into the contemplative spaces of high culture.”

“I had seen her work and I was blown away by the boldness of her color and the deepness of her subject matter,”Michelle Obama said of Sherald. ”And she walked in and she was so fly and poised.”

For her part Sherald thanked the former First Lady for being part of her vision.

Having her wear the dress from Michelle Smith’s label Milly, brought other artistic equations into the portrait, Sherald said.

“It has an abstract pattern that reminded me of the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian’s geometric paintings,” she said, “But Milly’s design also resembled the inspired quilt masterpieces made by the women of Gee’s Bend, a small, remote black community in Alabama where they compose quilts in geometries that transform clothes and fabric remnants into masterpieces.”

Sherald called the portrait “a defining milestone in my life’s work” because of what the former First Lady represents to the country: “a human being with integrity, intellect, confidence and compassion. And the paintings I create aspire to express these attributes: A message of humanity. I like to think they hold the same possibility of being read universally.”

Michelle Obama said at the unveiling that she was thinking of young people, “particularly girls and girls of color who in years ahead will come to this place and they will look up and they will see an image of someone who looks like them hanging on the wall of this great American institution. I know what kind of impact that will have on those girls, because I was one of those girls.”

Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama will take permanent installation in the recently refurbished “America’s Presidents” exhibit February 13 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Amy Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama will be on display in the museum’s “New Acquisitions” corridor through early November 2018.