Tanzila Ahmed, with a streak of purple in her hair and tigers’ faces glaring fiercely from the fabric of her dress, takes the stage at the Smithsonian’s 2017 Asian American Literature Festival. She opens a copy of her recent poetry chapbook and begins to read. Her voice, quiet and intimate, holds the audience in its grip:

I have lost my origin story

She is buried six feet under America’s soil

Wrapped in white

No nation state can define her now.

The lines from “Mom’s Belonging,” one of the poems in Ahmed’s collection “emdash & ellipses,” tells the story of her mother, who came from Bangladesh to the United States.

Organized by the Smithsonian’s Asian Pacific American Center (APAC), the three-day July literature festival was the first of its kind.

The Festival saw more than 80 Asian-American artists and writers arrive for events at the Phillips Gallery, the Library of Congress and the Dupont Underground. The authors came from a variety of cultural backgrounds, and in their diversity, demonstrated both the challenges and the opportunities of the growing Asian-American literary space and the museums that amplify its voices.

Ahmed was joined by three other Asian-American poets and novelists, who read their work at a session entitled, “Migration, Incarceration and Unity.” Japanese American Traci Kato-Kiriyama partnered with Ahmed to read a series of poems in dialog with one another.

In one, Ahmed imagines what would come of an encounter between their forebears—”if our grandfathers could meet.”

The Pakistani government jailed Ahmed’s Bangladeshi grandfather in the 1970s. She says he was incarcerated some six months at an internment camp outside of Lahore, Pakistan. Though Ahmed wasn’t born at the time, the memory of her grandfather’s internment, she says, resides deep within her bones.

Kato-Kiriyama’s grandfather, too, was interned at Manzenar, one of 10 American concentration camps in the United States where 110,000 Japanese-Americans were held during World War II. In her poems, she responded to Ahmed, expanding on the idea of their grandfathers’ shared experiences and how they impact their granddaughters:

I find myself in wonder

with each word I read

of the poems on your family –

What would it have been to

introduce our grandparents?

Would they have endured the summer heat

to dance in honor of our ancestors

and pick apart the proximity of

meaning to tradition?

Would they agree to disagree or

would they nod and say less

in order to hold the

future between us?

Their poetic conversation began a year and a half ago, and grew out of joint organizing between Los Angeles’ Japanese-American and Muslim-American communities. Ahmed joined a tour of the Manzenar Historic Landmark, organized by VigilantLove, a collective in Los Angeles that brings together Japanese and Muslim-Americans.

“For the pilgrimage day, thousands and thousands of people descend on Manzenar and after that day I wrote that poem,” Ahmed says.

“There’s a lot of talk now about ancestral trauma,” Kato-Kiriyama says.

But the poems are also a way to address the present and the future. Anti-Muslim sentiment within the United States has flared into political rhetoric over the past several years. Kato-Kiriyama says she sees Ahmed’s poems evolving out of “her thinking about her realities and the possibilities that the government is presenting to her and the entire Muslim community.”

For APAC director Lisa Sasaki, these opportunities for connection are one of the key reasons for organizing the Literature Festival.

“It’s writers and poets who are first able to put into words what we’ve internalized and aren’t able to express ourselves,” Sasaki says. “That’s why for me literature is so important regardless of the time period that we’re in, and why having writers and poets is so important to our American society as a whole.” Other sessions at the Festival tackled topics like gender, queerness and race.

As the founder of the Asian American Literary Review in Washington, D.C., Lawrence-Minh Bùi Davis, APAC’s curator of Asian Pacific American Studies, felt that the time was right for the festival.

“There’s been an explosion of Asian-American writers over the past five to 10 years,” he says. When asked why, he points to “changing attitudes about the place of the arts in Asian-American families.”

An increased interest in multiculturalism has also led to “greater familiarity with and demand for” Asian-American writing, he adds, including among Americans who aren’t of Asian descent. Organizations like Kaya Press, the Asian American Writers’ Workshop and Lantern Review, among others, have given financial and emotional support to a new generation of writers.

The Poetry Foundation, which publishes Poetry Magazine, agreed to launch a special issue in partnership with AALF. The poems in the issue demonstrate the diversity of Asian America. Rajiv Mohabir’s “Coolie” references a voyage from Guyana (Mohabir mixes Guyanese Creole, Bhojpuri and English in his poetry) while Wang Ping’s “Lao Jia 老家” (translation: “old home”) weaves together English and Chinese.

Many of the successful poems in the issue grapple with the unfinished movement between old homes and new. Many of the successful poems, like Oliver de la Paz’s “Autism Screening Questionnaire—Speech and Language Delay” and Ocean Vuong’s “Essay on Craft,” don’t deal explicitly with immigration at all.

Authors like Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge and the Pulitzer-prize winner Vijay Seshadri have been mainstays in the poetry community for decades. Their poems appear alongside writings by authors who have much shorter publication histories.

Like the magazine, the festival capitalized on diversity. In a literary address about the future of Asian-American poetics, Franny Choi brought her audience to tears of laughter when she described the angry poetry that she’s heard straight Asian-American men recite at poetry slams. That generation of poets, Choi contended, used poetry to strike back against a mainstream American media that they felt represented Asian men as asexual or lacking in virility.

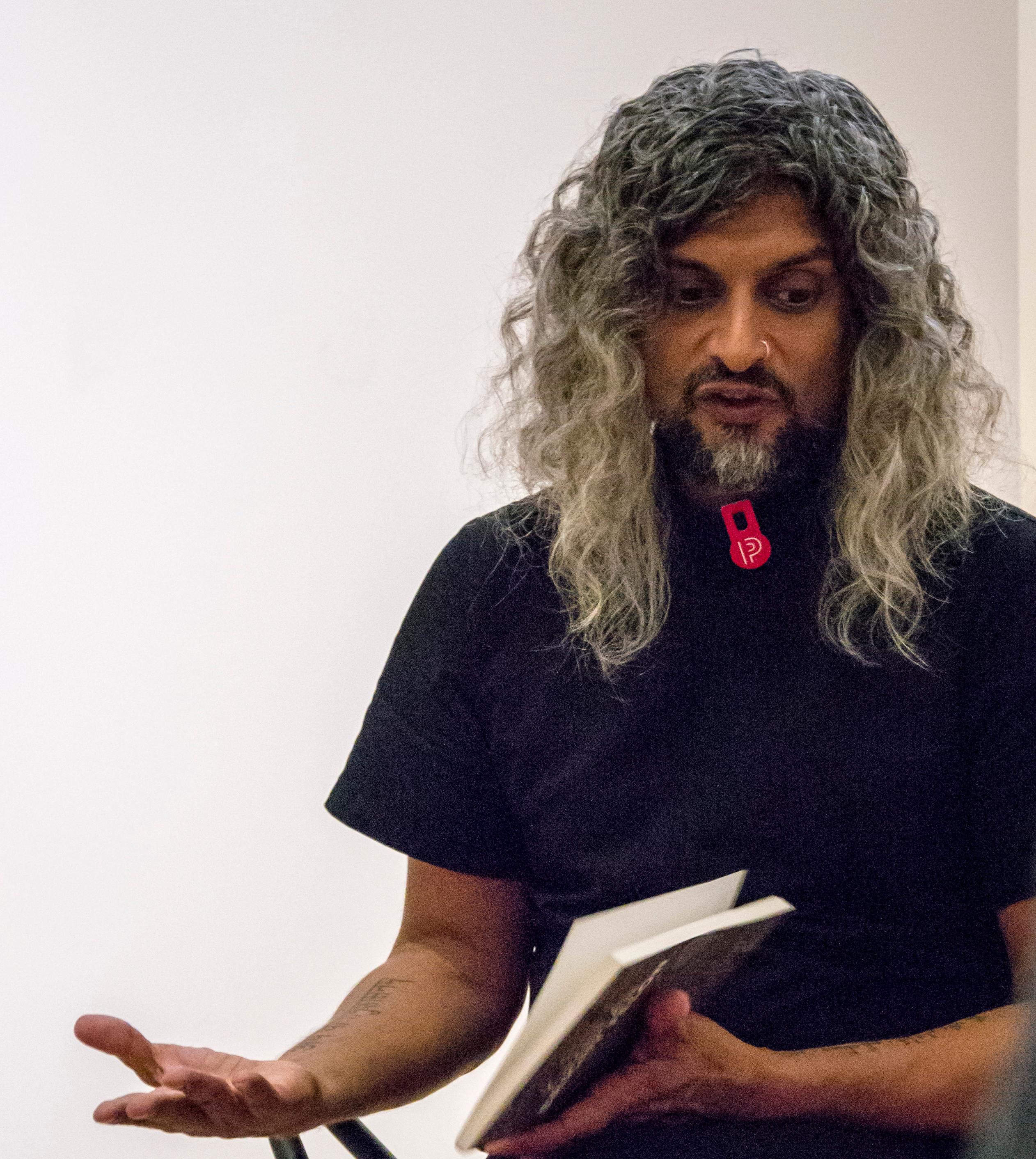

But a new generation of Asian-American poets celebrates queerness and fluid identity. The audience also heard from Kazim Ali, who has tackled the topic of queerness (of both genre and identity) for years.

Saturday’s events ended with a poetry slam and literaoke—literary karaoke—in the Dupont Underground, a stretch of old Metro track that’s now a venue for performance, film and theater. Amid graffiti and music, poet and congressional worker Louie Tan Vital read about her experiences working as a congressional staffer:

my family crushed the Pacific ocean

So I could cradle this democracy this allows you to break me

What a privilege to fall apart on these marble steps

What a privilege to break in this hallway

And have my community pick me back up

Because my family did not immigrate

For me to be silent

The audience snapped and cheered for their favorite writers, while sipping on beers and falooda (a sweet South Asian mix of rose syrup, vermicelli, jelly and milk.)

“There’s a perennial debate about what counts as Asian-American literature and who counts as Asian-American that came up across a number of talks,” says Davis. The term encompasses so many different languages, cultures and places in history, he points out.

As an organizer, his solution was to bring in as many types of literature as possible. “We included a panel on children’s literature, we had graphic novels, we commissioned an adaptation, we commissioned literary memes, we had maker-spaces and all this extra-literary or sorta-literary work, wanting to expand that category and think broadly about what that category can encompass.”

Certainly, Asian-American literary work has moved across genres. Writer and translator Ken Liu, whose fantasy novels, informed by Asian history and art, wrote a literary address for the festival. The organizers also commissioned Brooklyn-based graphic novelist Matt Huynh to create an animated adaptation of the prologue to The Committed, a forthcoming novel by Viet Nguyen, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Sympathizer.

“We had people [who] came in [to the festival] with questions like ‘what Asian countries will I see represented’ and got a little confused when the answer was ‘American, that’s the country you will see represented,” says Sasaki.

The organizers now want to expand the festival and maybe take it on tour, they say. Davis envisions a yearlong mentoring program, as well as an event in Chicago.

“I’ve put on a lot of public programs, but this is one that stands out in my mind simply for the number of people who came up to me to say that this was a program that was really needed,” Sasaki says. “We should be trying to meet those types of needs and we did it in this particular case.”