Ava Duvernay makes art that looks squarely at society and takes it to task. “Mass incarceration is important to me. The fracturing of the black family structure is important to me. The trauma of history on the black family unit is really important to me,” she says. She makes films because she wants to foster beauty in the world, because she wants to stir strong emotion in her viewers, but her art is also a weapon, which she wields carefully and lovingly because she believes in “fighting for justice, fighting for good.”DuVernay has directed shorts, documentaries, television series and feature films. With her second feature, Middle of Nowhere (2012), she became the first African-American woman to win the best director award at the Sundance Film Festival. This is why she can bring Martin Luther King Jr. (Selma) and Nova, Charley and Ralph Angel Bordelon (“Queen Sugar”)The series, based on the novel by Natalie Baszile and produced by Oprah Winfrey, examines the forces that unite and divide three siblings after their father dies, bequeathing them an 800-acre sugar farm in contemporary Louisiana. to life, make them so real and multidimensional that viewers care for them even as they rail against a world intent on cowing them. In the end, DuVernay is taking the things important to her—“representations of family, representations of black womanhood, representations of good over evil”—and crafting stories of fallible people we love.

When DuVernay was a childBorn in 1972, she grew up in Compton, south of downtown Los Angeles, and she graduated from UCLA with a degree in English and African-American studies. She made her directorial debut in 2008 with the hip-hop documentary This Is the Life, her Aunt Denise fostered a love of art in her, but also showed her that art and activism could be combined. Her aunt was a registered nurse who worked night shifts so she could “pursue her passion during the day, which was art and literature and theater….She was a patroness. She worked to live. But what she loved in life was the arts. She was fed by it,” says DuVernay. “That was a huge influence on me.” Her mother was socially conscious, and both women taught her that “you could say something through the arts.”

DuVernay is fearless despite working in an industry that hasn’t seen many black women who direct, write or maintain career longevity. She began as a publicist, and she was good at it. Over the years, she developed a voice and vision that flowered into reality as she made more films and documentaries and television that effortlessly combined art and activism across forms. When I ask her about her career, she says, “I try to be a shapeshifter and do a lot of things.Her next film is A Wrinkle in Time, based on the science fiction novel by Madeleine L’Engle. Scheduled for release in March, it is the first live-action feature film with a budget of $100 million or more to be directed by a woman of color. A: because I can. B: because the traditional walls collapsed so there’s more flexibility, and C: because you can’t hit a moving target.” Her social consciousness and her appreciation of good art not only inform her work, but they inform how she works as well. Planning for “Queen Sugar,” which has run for two seasons on the OWN network and has been approved for a third, she made a list of possible directors and then noticed that they were all women. “I thought: We should commit to this. At a time in the industry when there’s a lack of opportunity for women, we could really use our platform here to say something important about correcting a wrong.” A total of 17 women directed the 29 episodes of the first two seasons.DuVernay’s first directing job in scripted, non-documentary TV came in 2013, on the series Scandal. After other offers followed, she has said, she realized “what one episode of television can do for someone who hasn’t had it before.”

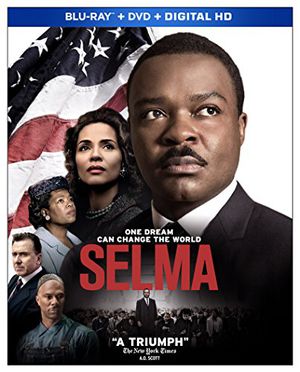

SELMA

SELMA is the story of a movement. The film chronicles the tumultuous three-month period in 1965, when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. led a dangerous campaign to secure equal voting rights in the face of violent opposition.

DuVernay’s perspective adds a revelatory dimension to the representation of black people in this country. We have decades of art, music, literature and film that bear testament to black Americans’ survival and drive to thrive in the United States. Much of it is powerful and moving. Often, it reconfirms our fire, our fight. Frequently, it reconfirms our agency and centers our stories. “All black art is political,” DuVernay told me. “I think our very presence is political. Anyone that is able to establish a voice and a consistent presence and put their voice forth is doing something radical and political with their very presence.”

But her work bears something more. It shows us an aspect of ourselves, of black people, that we rarely see on film: It allows us vulnerability. In “Queen Sugar” the characters, women and men and children alike, show emotion when they are sad or conflicted or in pain. They cry and sob and weep because they feel unappreciated or betrayed or angry or remorseful. They feel safe enough with one another, safe enough in the world, to bare their hearts with those they love. The experience of watching authentic vulnerability on the screen helps us to understand that we don’t have to be ever invulnerable, ever strong, ever inviolable, ever emotionless, even though this world seems to demand this of us. Instead, if we find ourselves in places of safety with people who engender that safety, we can let ourselves feel. DuVernay knows her show has this effect. “Some people say he [Ralph Angel] cries too much,” she says, laughing, “but it’s a very feminine, very caring show.” When I fell in love with “Queen Sugar” in the first episode, I realized how starved I’d been for emotionality in someone who looked like me.

DuVernay makes films that defy convention. Her films often seek to invert the tradition of the dehumanization of black people and the black body in the media. In the larger culture where the standard depiction of black people involves the exploitation of suffering, she wields the power of the image to jar her viewer into empathizing with suffering. She does this to devastating effect in 13thThe title refers to the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery, “except as a punishment for crime.” The film, a Netflix original, was nominated for an Academy Award and won four Emmy Awards and a Peabody Award., her documentary on racial injustices in the criminal justice system. The film shows one clip after another of black men and women who have been killed by police violence, so the audience is witness to one black person dying, and then another, and then another, even as a girlfriend sits in the passenger seat, documenting and crying, as a child whimpers in the back seat, shocked. The effect is immediate. By bracketing these images with testimony from academics, respected purveyors of truth, as they explain the horrors of police violence, the dehumanization of black people that enables multiple systems to fail us again and again, the costs of that dehumanization become clear. The viewer weeps at the torrent of human tragedy13th helped prompt the art collector and philanthropist Agnes Gund to sell a Roy Lichtenstein painting and use $100 million of the proceeds to start the Art for Justice Fund, which will promote changes in the criminal justice system. on the screen. There is no denial of police brutality, no room to posit, “But all lives matter.”

Yet DuVernay also encourages the viewer to appreciate the beauty of the black body and the vitality of black life through filming the black body with love. “Queen Sugar” opens with closeups of a woman’s arms and legs and hair, a woman we will later know as Nova, but the way the camera closely tracks her seems like a caress. This is beauty, we understand: this skin that shines, this hair that winds in a tangled fall. It’s true: DuVernay loves her characters. When asked about the subjects of her work, she says, “I’m not a director for hire. I choose what I do. Anything that I’m embracing is something that I’m involved in from the ground up. I do love everything that I’m doing, and I love the stories that I’m telling.”

We viewers understand this when we see Nova lovingly lit, when we see Charley framed by the landscape she’s fighting so hard to understand, when we see Ralph Angel’s face break when he’s standing in the fields he’s fighting so hard to hold on to. We see this refrain again in the credits of 13th, when photographs flash across the screen of black people, young and old, women and men and children smiling, hugging, riding horses and cooking.

“We are used to regarding ourselves in film as one-dimensional, one thing. That’s not true. We know we can be many things at once,” DuVernay says. “There are layers of dimension, of being, in one life, in one body. The goal is to show the different dimensions of us.”

At the close of 13th, the photographs, many of her family and friends, are a celebration of how complicated humanity can be. A fountain of black joy in the face of oppression. This is Ava DuVernay’s vision. This is her voice. She says: Here are people who love. Here are people who feel joy and tenderness and kindness. And in the end: Here are people who are.

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $12

This article is a selection from the December/January issue of Smithsonian magazine