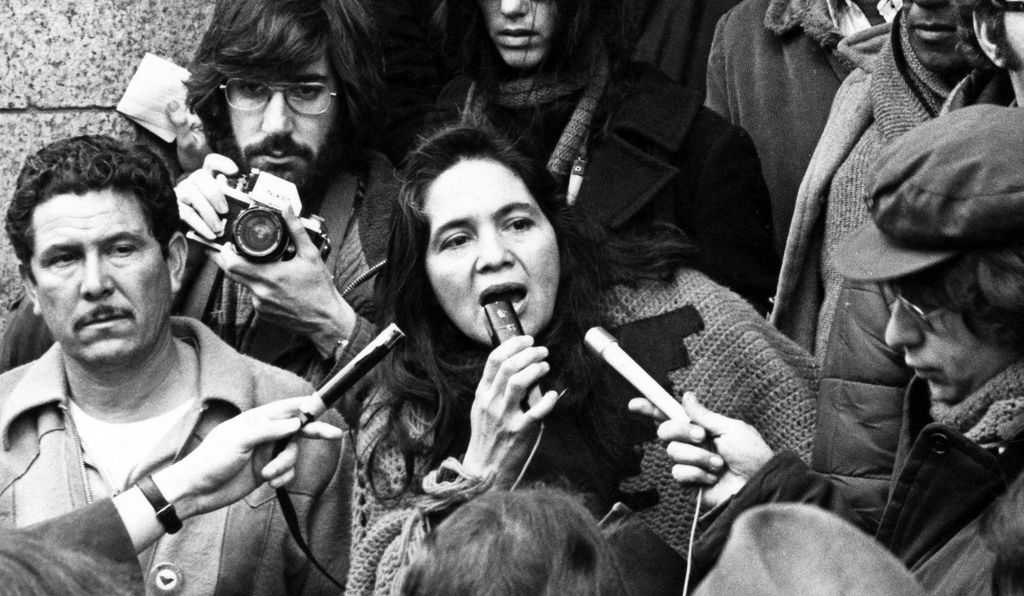

At a robust 87 years of age, Dolores Huerta speaks with the rapidity, clarity and conviction of her younger self. During the Civil Rights Era, Huerta co-founded what is now the United Farm Workers union, resolutely dedicating her life to securing the rights of immigrant farmworkers and to combatting the fierce racism underlying their mistreatment. In today’s political climate, she sees the fundamental freedoms of her fellow Americans freshly imperiled, and has come forward to share her story with a new generation of activists seeking to effect change.

Related Content

In part, this narrative will be disseminated via a new feature-length documentary, Dolores, directed by multiple film festival award-winner Peter Bratt and slated for release this September. A preview screening will be held the evening of Tuesday, August 29, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

The film opens with a humble view of Huerta applying makeup in a hotel before a speaking engagement, but quickly plunges its viewers into the maelstrom of postwar America, revealing the passion and dynamism lurking beneath Huerta’s now-calm exterior.

Following her parents’ divorce in 1933, Huerta moved with her mother to Stockton, California, where she soon developed an affinity for the hard-working immigrants who labored under a brutal sun for little pay and less respect. Her father, a former coal miner, had risen to become a union leader and member of the New Mexico state legislature. Young Dolores was keen to make a difference too.

Huerta earned her associate’s degree from a local college, and tried her hand at teaching. She found that economic inequality had set her students so far back that her time would be better spent agitating for change on their parents’ behalf.

She joined the Stockton Community Service Organization (CSO), a local group committed to improving quality of life for Mexican-Americans through community action and political engagement. Employing her natural gift for persuasive oratory, Huerta proved herself a highly capable lobbyist. Refusing to take no for an answer, she fought for community betterment programs and protective legislation.

When Huerta and César Chavez—also a member of the CSO—cofounded the National Farm Workers Association (now the United Farm Workers) in 1962, they rocketed to national prominence. Operating out of Delano, where they had embedded themselves among a community of Mexican-American farmhands, Huerta and Chavez orchestrated large-scale labor actions, including a massive strike, and enlisted the American public in their efforts to safeguard some of the country’s toughest workers.

Bratt’s film highlights Huerta’s role in the campaign to outlaw DDT—a popular pesticide which posed serious health risks to agricultural laborers—as well as the national boycott of California table grapes, Gallo-brand wine and lettuce.

The boycott brought Huerta to New York City, where she connected with Gloria Steinem and other members of the burgeoning women’s movement. The feminist perspective would come to inform her activist ethos going forward. Huerta had first-hand experience with patriarchic unfairness; many of the farmworkers for whom she was fighting stubbornly clung to the idea that their real leader was César Chavez, and that Huerta was strictly a subordinate—one who should do less of the talking.

Little did they know the extent to which her talking was helping the movement. Huerta’s lobbying led to the passage of key California legislation, including Aid for Dependent Families in 1963 and the Agricultural Labor Relations Act in 1975. Over the course of her career, Huerta ensured for farmworkers in her state the right to organize and bargain with their employers.

Though set back by a vicious police beating during a late-1980s protest, and alienated from the UFW following the death of César Chavez, Dolores Huerta never gave up. To this day, she is an outspoken critic of economic and racial injustice wherever she sees it, and her eponymous foundation wages legal battles on behalf of Californians of color disadvantaged by institutionalized prejudice.

In many ways, however, the story of the film, Dolores, is the story of the power of all American people, not merely that of a lone crusader. Through sustained use of lively archival footage, director Bratt immerses his viewer in the overwhelming humanity of the civil rights struggle. The screen is often filled with the animated bodies of protestors, and when it isn’t, interviews with a wide array of supporting characters flesh out and globalize Huerta’s experience.

“The farmworkers couldn’t win by themselves,” Huerta said recently in a telephone interview. “They had to reach out to the American public, and all of the 17 million Americans that decided not to eat grapes or lettuce and Gallo wine. And that’s the way that we won.”

Huerta points to a line in the film delivered by Robert Kennedy, a staunch ally of the farmworkers’ movement before his tragic assassination in June of 1968. “What he said was, ‘We have a responsibility to our fellow citizens.’ And I think that is what we’re having to do—to take those words and put life into them, realizing that all of us have a responsibility.”

She is not speaking solely on the plight of agricultural laborers. To Huerta, and to the filmmakers, recent events have made abundantly clear the need for across-the-board support for the rights of people of color in this nation and worldwide.

“Eight years ago,” says director Peter Bratt, “we were supposedly a ‘post-racial’ society, and now you have thousands of young white men marching in the streets with hoods and KKK signs and swastikas. And I think it’s bringing to the fore something we need to pay attention to that we’ve kind of swept under the rug. It’s like a boil that’s burst open, and we have to address it.”

In Huerta’s experience, the most effective way to replace corrupt policies is by getting out the vote. “I applaud [today’s activists] for the protests and for the marches and all that that they’re doing, but it’s got to translate into voting. The only way we can change the policy that needs to be changed is by sitting on those seats of power where decisions are being made about how our money’s going to be spent, what our policies are going to be.”

Then, once the people have a voice, Huerta says, they can use it to reform the educational system. Incorporating diverse and underrepresented perspectives into elementary, middle and high school curricula will—the theory goes—lead to open-minded, understanding adults.

“We have never taught in our schools that indigenous people were the first slaves, that African slaves built the White House and Congress,” Huerta says, nor addressed the “contributions of people from Mexico, and Asia, that built the infrastructure of this country. If people grew up with that knowledge, they would not have that hatred in their hearts against people of color.”

Director Bratt points out that Huerta’s own inspiring narrative is rarely told. “People come out [of the theater] and say, ‘Oh my God. I had no idea. I had never even heard of Dolores Huerta.’ So the fact that someone who played such an important role historically in the Civil Rights Movement, and moving legislation that we enjoy today, the fact that educated women who even teach ethnic and women’s studies didn’t know her story—to me, that was an awakening.”

Huerta hopes that young people will see the film and take inspiration from her example. She understands the impulse to be angry at events unfolding in America today, but is careful to note that anger must always be channeled into nonviolent action to be useful. Destruction and rage, she says, will get oppressed peoples nowhere.

“We can win through nonviolence,” she says. “Gandhi did it in India—he liberated a whole country using nonviolence. And people who commit violence, you’re actually joining the other side. You’re joining the alt-right, you’re joining the Nazis and all those people who think they have to use violence against other people to get their views across.”

The story of Huerta’s own life—the story of Dolores—is a testament to the impact that sustained, nonviolent activism can have on a society.

“The poorest of the poor of the farmworkers—the most denigrated and humiliated people—came together and were able to have enough power to overcome the president of the United States, Richard Nixon, the governor of California, Ronald Reagan, the big farm organizations. . . and win.” she says.

“And I think that’s the message that people need to hear today. Not to despair, but we can actually come together and make this happen. Create a better nation.”

The documentary Dolores will be screened August 29, 2017, at 7 p.m. at the National Museum of the American Indian. A moderated discussion with Dolores Huerta and director Peter Bratt (Quechua) following the showing of the film.