Two years ago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., celebrated the 150th birthday of Edvard Munch with an exhibition featuring “The Scream,” the famous personification of the Norwegian master’s struggle with agoraphobia. In it, a genderless protagonist confronts a nightmarish sunset of shrieking reds, burning yellows, and stormy blues.

The show told the story of how Munch elevated his personal experiences into the universal. As a blurb from the exhibition notes: “The real power of his art lies less in his biography than in his ability to extrapolate universal human experiences from his own life.” Or, in other words, you don’t exactly need to understand the context of “The Scream” to understand, well, that scream.

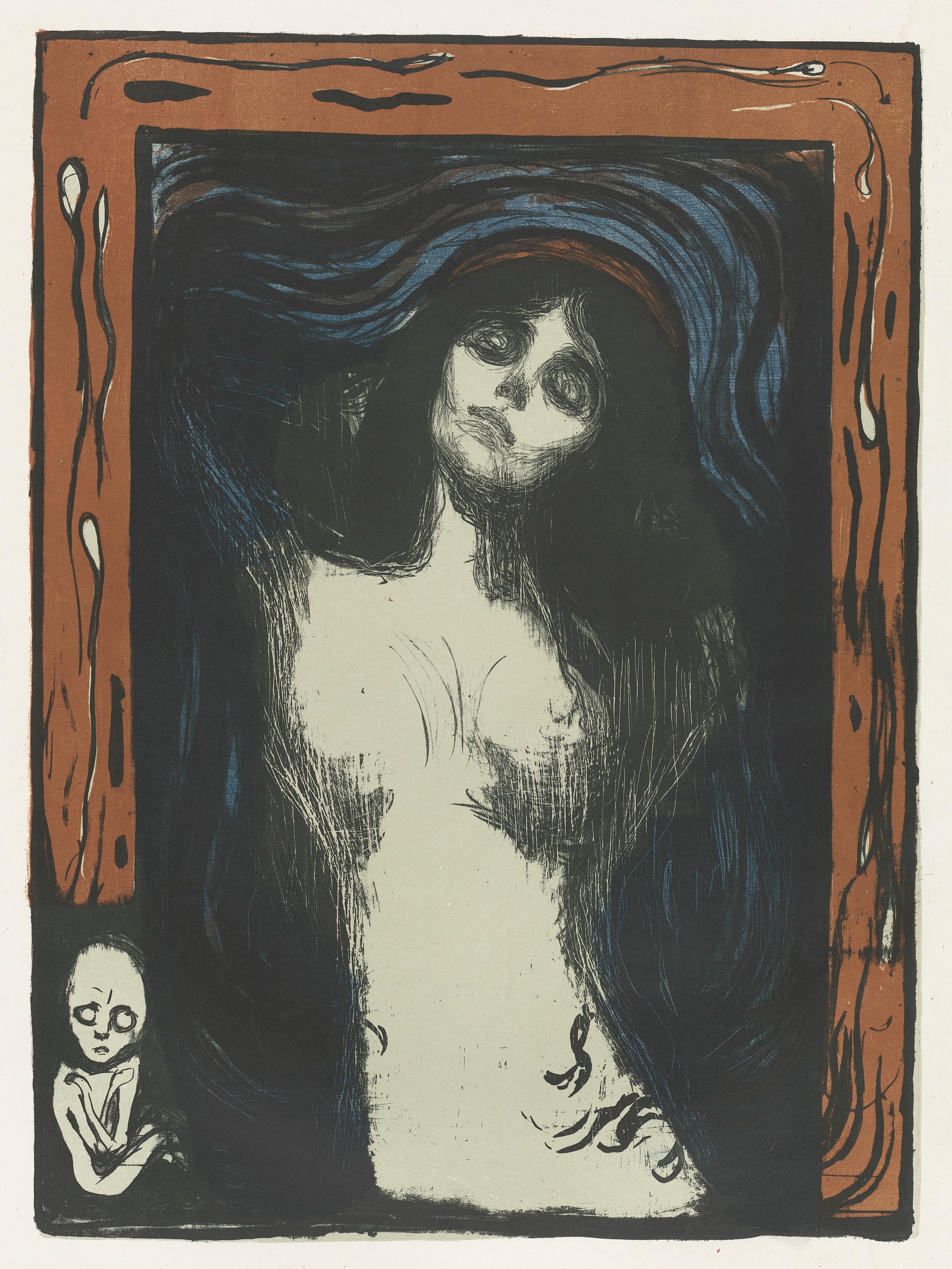

Now, the National Gallery is revisiting the master painter and printmaker, this time in an exhibition exploring how his color choices tell a larger story of his age. Featuring a selection of 21 prints, “Edvard Munch: Color in Context,” which is on view through January 28, 2018, makes a case for how Munch’s feverish palettes and unnerving use of color in his work—especially his prints—reflect the emerging scholarship of the late 19th century, when scientists, academics and philosophers sought to bridge the gap between the real and invisible world.

Mollie Berger, curatorial assistant for the department of prints and drawings, organized the small exhibition after reconsidering Munch’s prints. “Looking at the prints I thought, the color is phenomenal, and that’s really to me what comes across,” she says. “In the past, often scholars have said these prints are all about his internal angst or what was going on with his life, but I think in some ways he’s also trying to communicate with us.”

Munch came of age at a time when everything humans knew about the natural world was changing: Physicist George Johnstone Stoney discovered the electron; photographer Eadweard Muybridge captured the first fast-motion image; Wilhelm Roentgen unlocked the power of the x-ray. The naked eye was no longer seen as a truth teller, but rather something that obscured the intangible realms.

Munch was particularly receptive to the idea of invisible energies and dimensions. Death had followed the artist, born in 1863 and raised in Oslo; as a child, he lost his mother and sister Sophie. In early adulthood, his father died, and soon after, another sister, Laura, had to be committed to an asylum.

After Munch ditched his schooling in engineering to pursue art, he found his voice in the symbolism movement, identifying with contemporaries such as author Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who he believed had “penetrated…into the mystical realms of the soul,” in a way that no artist had yet. Early in his career, Munch described his own artistic choices in a similar vein, saying, “I felt I should make something—I thought it would be so easy—it would take form under my hands like magic. Then people would see!”

Literal magic wasn’t so far off from what Munch was looking to capture. The scientific advancements of the day also ushered in a golden age of belief in supernatural forces and energies, and symbolists, in turn, were heavily influenced by the occult and the dream world. As a young artist, Munch took to hanging out in the spiritualist and theosophist circles, and questioning the presence of the soul.

“He was certainly interested and fascinated by it,” says Berger. “He didn’t have crazy visions like [August] Strindberg would have but, according to his friend Gustav Schiefler, Munch did claim to see auras around people.”

The theosophical idea of psychic auras, or colors influenced by emotions and ideas, was a popular theory of the day, advanced by Annie Besant and Charles W. Leadbetter in their influential 1901 book, Thought-Forms. While there is no proof that Munch pulled directly from the book when creating his own palette, Berger includes their color key in the show, and it’s tempting to draw parallels between Munch’s choices and their work, which pegs colors like a bright yellow to “highest intellect,” muddy brown as a stand in for “selfishness” and deep red for “sensuality.”

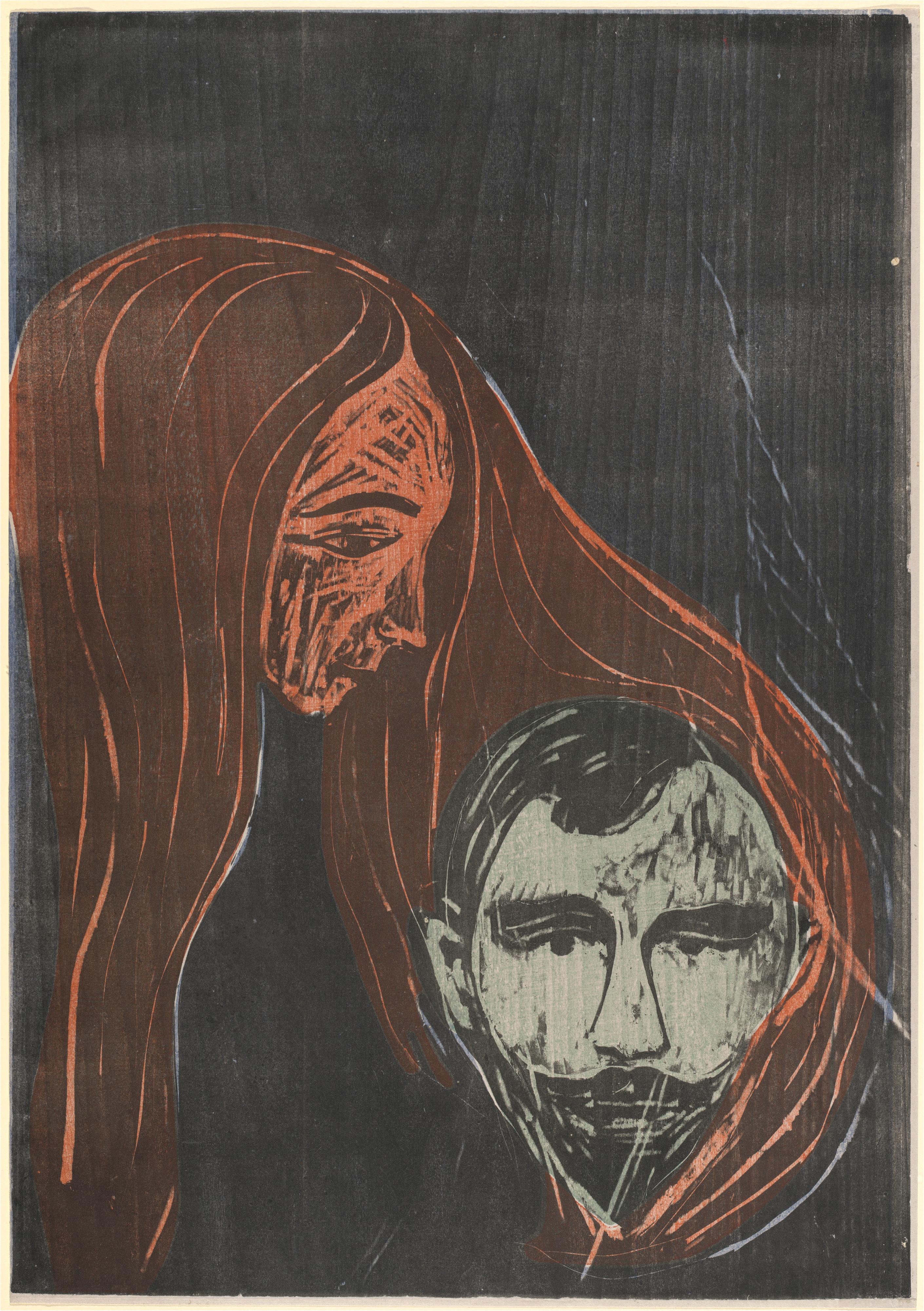

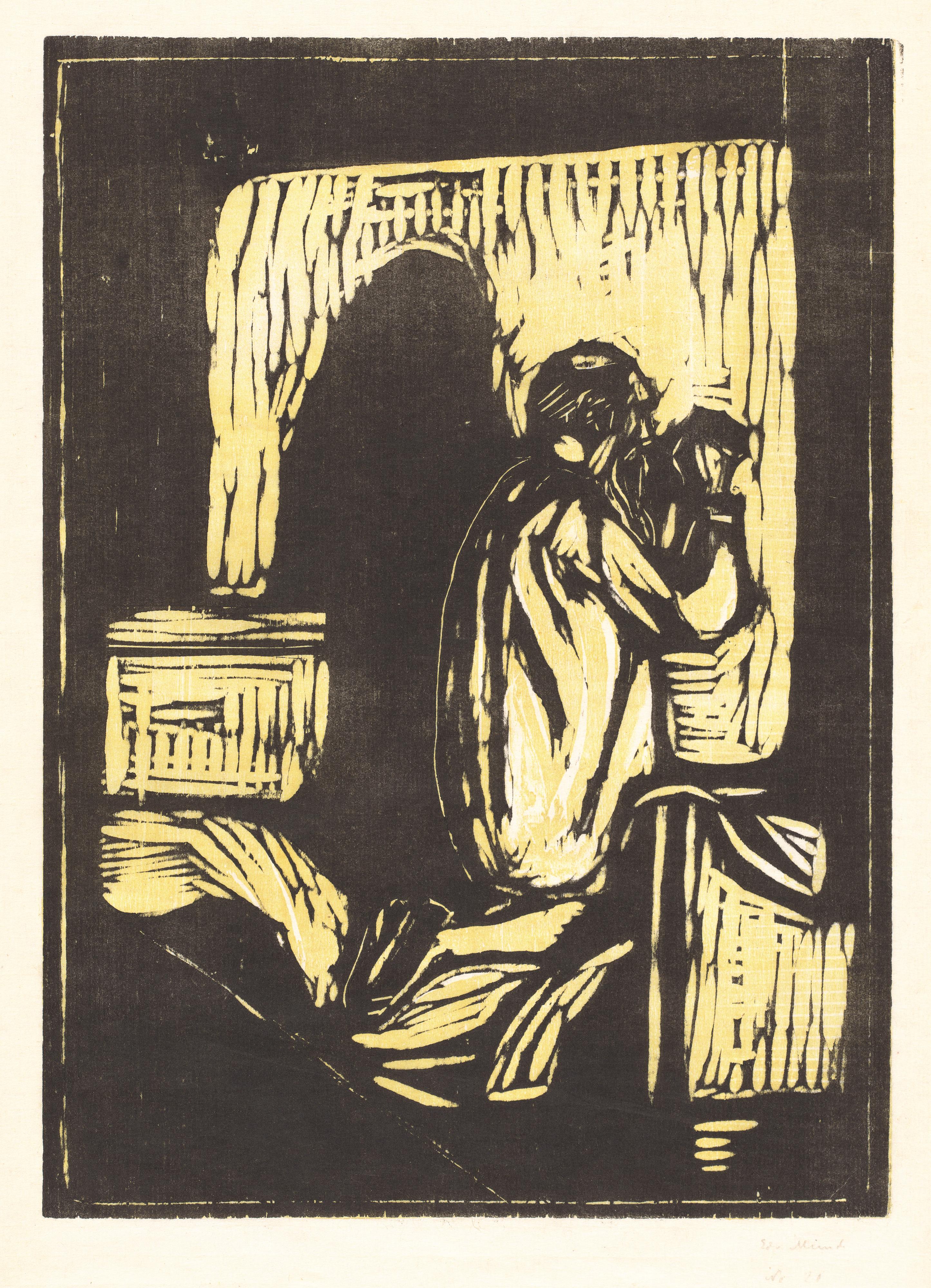

Munch’s prints, especially, connect the idea of color and physic auras, Berger argues. The medium—less expensive to make than his paintings—freed the artist up for experimentation, she explains, and the singular color choices he employs to powerful effect do present a compelling narrative. For example, in one 1895 composition, “The Vampire,” a woman’s hair splays over a man, who leans into her in a passionate embrace. The seductive visual, however, takes on a new meaning if you consider the retouched proof made before the final woodcut, on view in the exhibition, where the arm of the woman and the face of the man is splashed with yellow, or high intellect. Under that light, the artwork instantly shifts to a more contemplative, romantic story, more befitting of Munch’s original title for the work, “Love and Pain.”

Berger believes Munch is one of the artists of his age who is most dedicated to the theosophical ideas of color choice. “For me, with Munch, the color is paramount,” says Berger. “I don’t see really anything else.”

His selection and combination can be so compelling that it’s tempting to suggest Munch had a form of synesthesia, where one sense causes a sensation in another, though he was never diagnosed with it during his lifetime. “Scholars have said, of course, Munch had synesthesia. But people say that about [Wassily] Kandinsky too,” says Berger. “I think all artists on some level have that relationship with color and perception because I feel like you have to on some degree to be an artist. You have to see color differently than other people to be so drawn to it and follow that path in life.”

In the exhibition, Munch’s metaphysical influences arguably come most in focus in “Encounter in Space.” The 1902 abstract etching, which would feel at home in “The Twilight Zone,” depicts orange-red and blue-green masses of humanity, which appear to float across a void that might as well be the fourth-dimension. The color selections, which according to Thought-Forms translate as pure affection and devotion or sympathy, respectively, tell a hopeful story. Though Munch’s own life was full of hardship, this reading of the work suggests that perhaps he hoped the invisible world that he captured in his art was a kinder one.