The Miss America pageant has never been a progressive event, but in 1968, it sparked a feminist revolution. As women organized the first protest against Miss America, they were responding not only to the pageant and its antiquated, misogynistic attitudes toward women and beauty, but also to how the United States, as a whole, treated women.

The 1968 uprising was conceived by a radical feminist named Carol Hanisch, who popularized the phrase, “The personal is political.” Disrupting the beauty contest, she thought, in the summer of that year, “just might be the way to bring the fledgling Women’s Liberation Movement into the public arena.”

Like so many things, the Miss America pageant began as a marketing scheme. Held in Atlantic City just after Labor Day, it started in 1921 as a way for newspapers to increase their circulation and for the resort’s businesses to extend their profitable summer season. Newspapers across the country held contests judging photographs of young women, and the winners came to Atlantic City for a competition where they were evaluated on “personality and social graces.” There was no equivocating. Women’s beauty—white women’s beauty—was a tool.

Since its inception, the pageant has evolved in some ways and not so much in others. The talent competition was introduced in 1938 so that perhaps the young women could be judged on more than just their appearance, but with that small bit of progress came regression. That same year, the pageant chose to limit eligibility to single, never-married women between the ages of 18 and 28. The kind of beauty the pageant wanted to reward was very specific and very narrow—that of the demure, slender-but-not-too-thin woman, the girl next door with a bright white smile, a flirtatious but not overly coquettish manner, smart but not too smart, certainly heterosexual. There was even a “Rule 7,” abandoned in 1940, that stated that Miss America contestants had to be “of good health and of the white race.” The winner spent the year doing community service, but also peddling sponsors’ products and, later, entertaining U.S. troops.

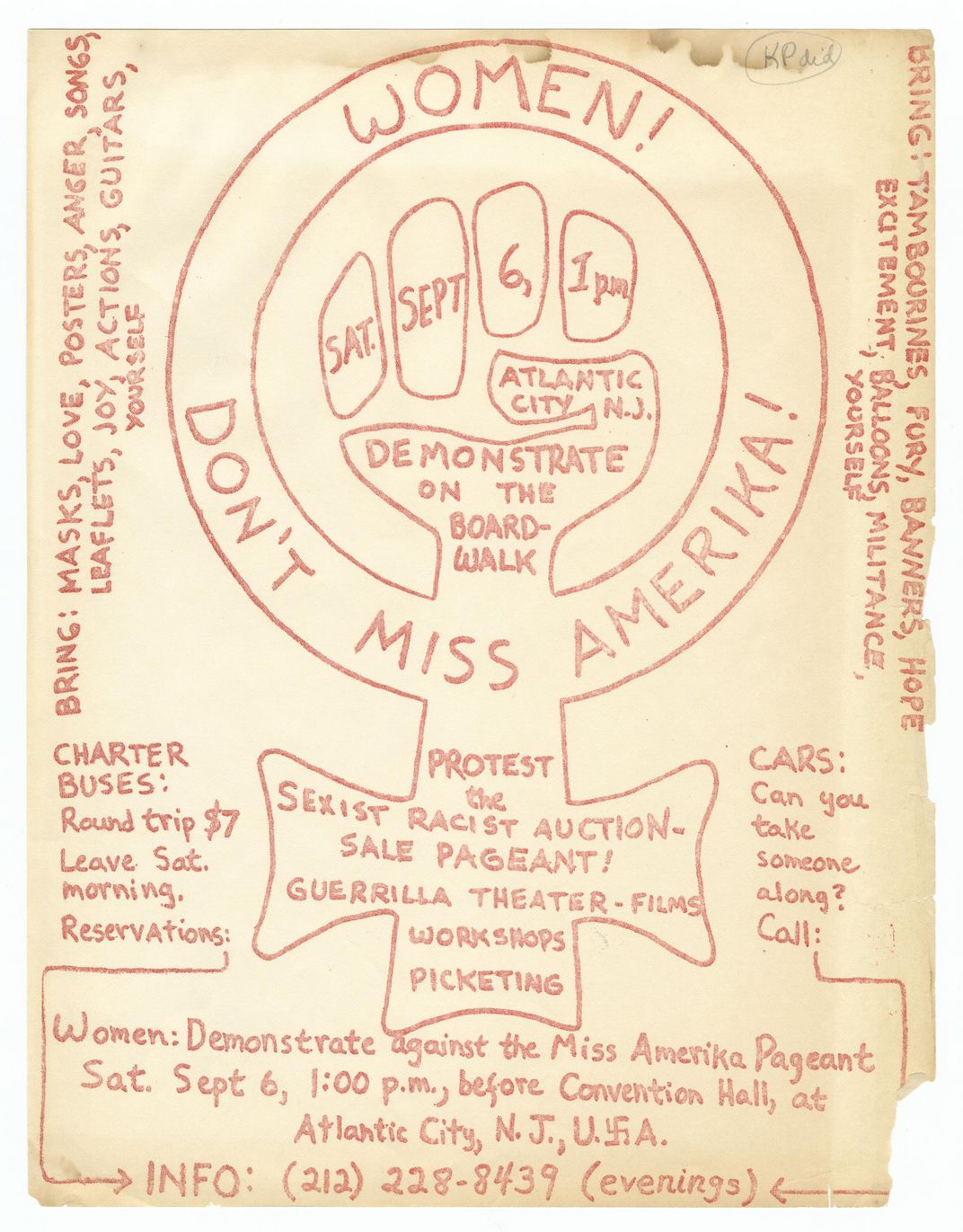

To Hanisch and the other protest organizers, the pageant was an obvious target. On August 22, the New York Radical Women issued a press release inviting “women of every political persuasion” to the Atlantic City boardwalk on September 7, the day of the contest. They would “protest the image of Miss America, an image that oppresses women in every area in which it purports to represent us.” The protest would feature a “freedom trash can” into which women could throw away all the physical manifestations of women’s oppression, such as “bras, girdles, curlers, false eyelashes, wigs, and representative issues of Cosmopolitan, Ladies’ Home Journal, Family Circle, etc.” The organizers also proposed a concurrent boycott of companies whose products were used in or sponsored the pageant. Male reporters would not be allowed to interview protesters, which remains one of the loveliest details of the protest.

The organizers also issued a document offering ten reasons why they were protesting, with detailed explanations—a womanifesto, if you will. One contention was “the degrading Mindless-Boob-Girlie Symbol.” Another was racism, since a woman of color had never won—and there had never been a black contestant. “Nor has there ever been a true Miss America—an American Indian,” they wrote. They also protested the military-industrial complex and the role of Miss America as a “death mascot” in entertaining the troops. They pointed to the consumeristic nature of corporate sponsorship of the pageant and the valuing of beauty as a measure of a woman’s worth. They lamented that with the crowning of every new Miss America, the previous winner was forced into pop culture obsolescence. They rejected the double standard that contestants were forced to be “both sexy and wholesome, delicate but able to cope, demure yet titillatingly bitchy.” The pageant represented the elevation of mediocrity—American women were encouraged to be “unoffensive, bland, apolitical”—and instilled this impoverished ambition in young girls. “NO MORE MISS AMERICA,” the womanifesto proclaimed.

The organizers obtained a permit, detailing their plans for the protest, including barring men from participating, and on the afternoon of September 7, a few hundred women marched on the Atlantic City boardwalk, just outside the convention center where the pageant took place. Protesters held signs with such statements as “All Women Are Beautiful,” “Cattle parades are demeaning to human beings,” “Don’t be a play boy accessory,” “Can make-up hide the wounds of our oppression?”

The protesters adopted guerrilla theater tactics, too. One woman performed a skit, holding her child and pots and pans, mopping the boardwalk to exemplify how a woman’s work is never done. A prominent black feminist activist and lawyer, Florynce Kennedy, who went by Flo, chained herself to a puppet of Miss America “to highlight the ways women were enslaved by beauty standards.” Robin Morgan, also a protest organizer, later quoted Kennedy as comparing that summer’s violent protests at the Democratic National Convention to throwing a brick through a window. “The Atlantic City action,” Kennedy continued, “is comparable to peeing on an expensive rug at a polite cocktail party. The Man never expects the second kind of protest, and very often that’s the one that really gets him uptight.”

The freedom trash can was a prominent feature, and the commentary about its role in the protest gave rise to one of the great misrepresentations of women’s liberation—the myth of ceremonial bra-burning. It was a compelling image: angry, unshaven feminists, their breasts free from constraint, setting fire to their bras as they dared to demand their own liberation.

But it never actually happened. In fact, officials asked the women not to set the can on fire because the wooden boardwalk was quite flammable. The myth can be traced back to the New York Post reporter Lindsy Van Gelder, who, in a piece before the protest, suggested protesters would burn bras, a nod to the burning of draft cards. After other Post writers reported the idea as fact, syndicated humor columnist Art Buchwald spread the myth nationwide. “The final and most tragic part of the protest,” he wrote, “took place when several of the women publicly burned their brassieres.” He continued to revel in his misogyny, writing, “If the average American female gave up all her beauty products she would look like Tiny Tim and there would be no reason for the American male to have anything to do with her at all.” In a handful of sentences, Buchwald neatly illustrated the urgent need for the protest.

During the actual pageant that evening, some of the protesters, including Carol Hanisch, sneaked into Boardwalk Hall and unfurled a banner reading, “Women’s Liberation,” while shouting, “Women’s Liberation!” and “No More Miss America!” Their action gave the burgeoning movement an invaluable amount of exposure during the live broadcast.

At midnight on September 8, a few blocks away at the Atlantic City Ritz-Carlton, the inaugural Miss Black America competition was held. If the Miss America pageant wouldn’t accommodate black women and black beauty, black folk decided they would create their own pageant. After his daughters expressed their desire to become Miss America, the Philadelphia entrepreneur J. Morris Anderson created Miss Black America so his children’s ambitions would not be thwarted by American racism. The 1968 winner, Saundra Williams, reveled in her win. “Miss America does not represent us because there has never been a black girl in the pageant,” she said afterward. “With my title, I can show black women that they too are beautiful.” In 1971, Oprah Winfrey participated in Miss Black America as Miss Tennessee. The pageant, which continues today, is the oldest pageant in the country for women of color.

While the 1968 protests may not have done much to change the nature of the Miss America pageant, they did introduce feminism into the mainstream consciousness and expand the national conversation about the rights and liberation of women. The first wave of feminism, which focused on suffrage, began in the late 19th century. Many historians now credit the ’68 protest as the beginning of feminism’s broader second wave.

As feminists are wont to do, the organizers were later relentless in critiquing their own efforts. In November 1968, Carol Hanisch wrote that “one of the biggest mistakes of the whole pageant was our anti-womanism…Miss America and all beautiful women came off as our enemy instead of our sisters who suffer with us.”

History is cyclical. Women are still held to restrictive beauty standards. Certainly, the cultural definition of beauty has expanded over the years, but it has not been blown wide open. White women are still upheld as an ideal of beauty. In the Miss America competition, women are still forced to parade around in swimsuits and high heels. “The swimsuit competition is probably the most honest part of the competition because it really is about bodies; it is about looking at women as objects,” Gloria Steinem said in the 2002 film Miss America.

History is cyclical. As we look back on these 1968 protests, we are in the midst of another significant cultural moment led by women. After the election and inauguration of President Trump, millions of women and their allies marched in the nation’s capital and in cities around the world to reaffirm women’s rights, and the rights of all marginalized people, as human rights. They marched for many of the same rights the 1968 protesters were seeking. A year later, we are in the midst of a further reckoning, as women come forward to share their stories of workplace sexual harassment and sexual violence. And, for the first time, men are facing real consequences for their predation. The connective tissue between 1968 and now is stronger than ever, vibrantly alive.

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $12

This article is a selection from the January/February issue of Smithsonian magazine