On April 27, 1931, at the Galerie Percier on the Right Bank of Paris, Alexander Calder presented some 20 pieces of abstract sculpture that would turn out to be a game changer—for Calder, for the Parisian avant-garde, and for the art of sculpture in the 20th century.

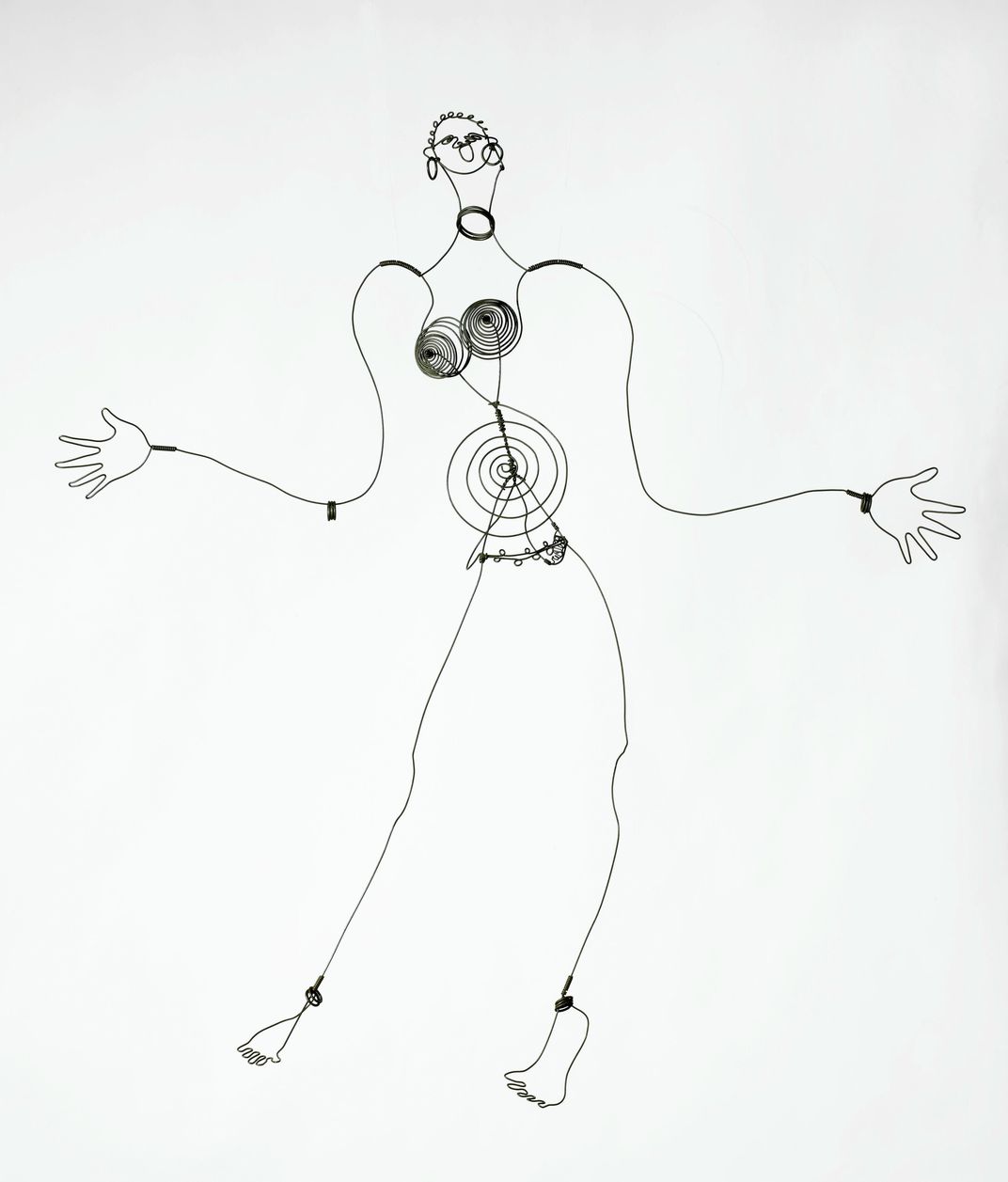

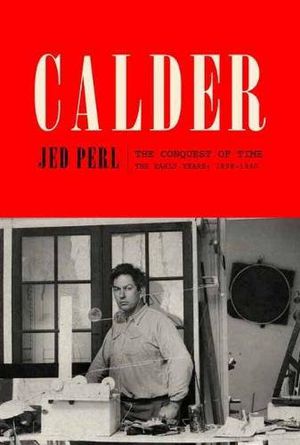

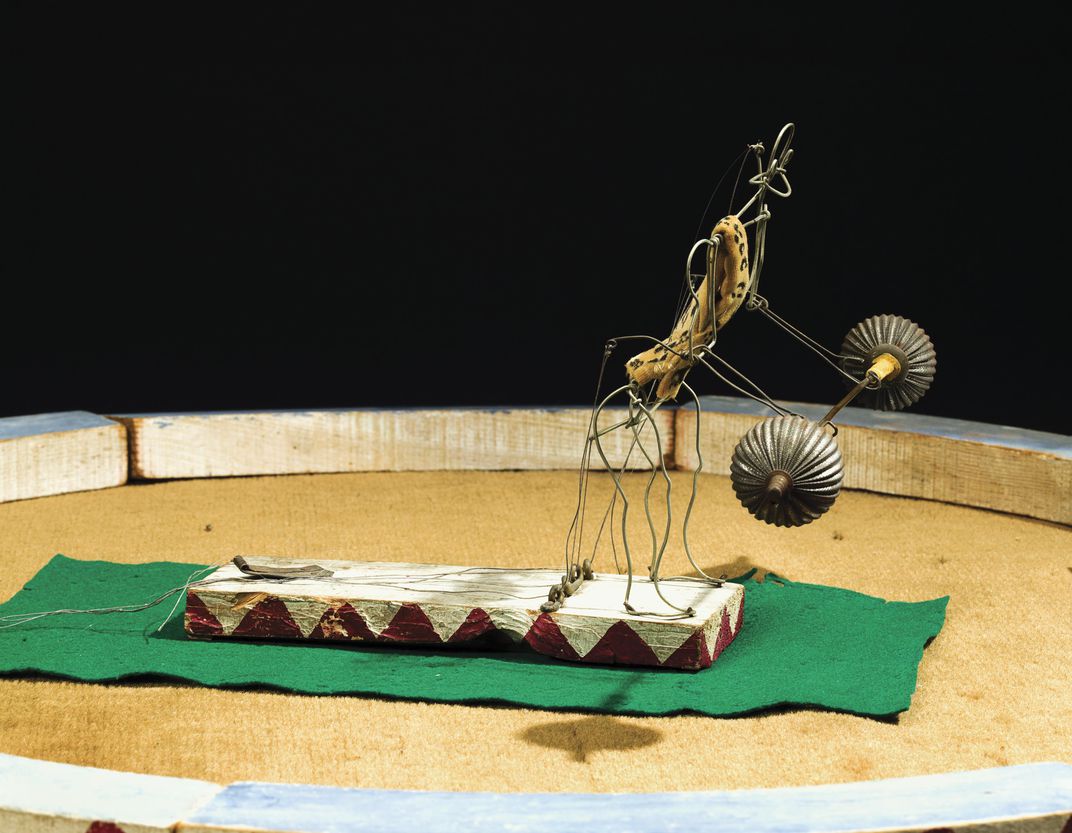

Calder had first arrived in Paris from New York five years earlier, in 1926, at the age of 28, and he had been moving back and forth between the two cities ever since. He was already well-known on both sides of the Atlantic as the creator of beguiling, dazzling wire sculptures of men, women and animals. And the performances he mounted of his miniature Cirque Calder—whimsical wire figures, including a horse, acrobats and trapeze artists, placed inside a small-scale ring and animated by hand or from suspended wires by Calder himself—had been attended by a who’s who of the Parisian artistic world, including Jean Cocteau, Fernand Léger, Man Ray and Piet Mondrian.

The Galerie Percier show, however, was a shock. Nobody had ever seen abstract sculpture of such austere lucidity. Arranged on a long, low platform, these works had an eloquence that was rooted in the artist’s simplicity of means—in something as basic as the elegance with which wire elements were attached to one another. The show’s title contained the enigmatic words “Volumes—Vecteurs—Densités.” This put visitors on notice that Calder was exploring the nature of volumes and voids and movements through space. The work was a deep dive into the nature of nature.

Consider the work titled Croisière. This daringly simple composition consisted of two intersecting circles to which Calder had added a curving length of thicker rod and two small spheres, painted in white and black. A croisière can be a cruise on a boat. In a preliminary list of titles, there was a slightly more elaborate version: Croisièredans l’espace—in other words, Cruise Through Space. Working as a minimalist, Calder was mapping a complex, cosmological scheme. Croisière was about the everything and the nothing of the universe. Calder was aiming to grasp the ungraspable, to describe the indescribable.

Late in May, Calder wrote to tell his sister, Peggy, back in the States, that although he hadn’t sold anything from the Galerie Percier show, it “was a real success among the artists.” Picasso, who lived down the street from the gallery and was never one to miss a new turn in the story of modern art, appeared even before the opening. Léger, one of the most respected and adventuresome artists of the day, composed a few precious words for the exhibition’s catalog that welcomed Calder into the most exalted circles of the Parisian avant-garde: “Looking at these new works—transparent, objective, exact—I think of Satie, Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, Brancusi, Arp—these unchallenged masters of unexpressed and silent beauty. Calder is of the same line.”

While “Satie and Duchamp are 100 percent French,” Léger noted, Calder “is 100 percent American.”

**********

Calder had been born in Philadelphia in 1898 into a family of artists. His father, A. Stirling Calder, was much admired and sought after as a creator of large-scale public sculptures in the early decades of the 20th century. His mother, Nanette Lederer Calder, was an accomplished painter and a pioneering feminist. Calder had considered a career in engineering before embracing the visual arts in 1923, when he began studying at New York’s Art Students League.

Within several years, Calder’s figure sculptures had already gained him a reputation as a troubadour of the giddy high spirits of the Roaring Twenties on both sides of the Atlantic. But no one could have foreseen the breakthrough of the Galerie Percier show. Suddenly, Calder was now being embraced as a prophet of the increasingly austere mood of the early 1930s—of a world descending into the Depression and political crises on the left and the right. Working as an abstract artist, Calder was reaching for a contemplative, almost quietistic mood.

What had changed? In the years 1929 and 1930 Calder had made two life-changing decisions: He became a married man and an abstract artist. These were the foundations on which he would build for the rest of his life.

Calder’s anni mirabiles began in the summer of 1929, when Calder decided to make yet another of his trips back to New York and booked passage on a French ocean liner, the De Grasse. For the 29-year-old artist, who had worked his way to San Francisco and later to Europe as a crew member on a couple of rusty old boats, being a paying customer on the De Grasse—a luxurious ship with an indoor swimming pool and a spectacular dining room—must have been heaven. Calder regarded himself as a fairly experienced seaman after those earlier voyages. He believed that moving as much as possible was the best way to avoid seasickness, so he made it a habit to circulate on the deck. Early in the crossing, as he made his rounds, he came up behind a young woman, accompanied by a man who was her father or at least old enough to be.

Wanting to get a better look, he reversed direction, and after passing the couple and discovering that she was indeed attractive, with blue eyes and thick, light hair, he made a point on his next pass around the deck of wishing them, “Good evening!” To this, Calder remembered years later, he heard the older man say to the young woman, “There is one of them already!” Apparently Calder had been identified as a young man on the make. As for the couple Calder was making it his business to get to know, the man was Edward Holton James, and the woman was his daughter Louisa James.

We do not need to imagine what attracted Sandy when he caught sight of Louisa taking her constitutional, for there is a photograph of her sitting on the rail of the De Grasse. Her cloche hat, her pearl necklace and her fur stole are sleek and elegant, framing her bright eyes and open, smiling lips. She regards the camera with a look that’s frank. Louisa, 24 years old, had been born in Seattle, Washington, the youngest of three daughters. She was no stranger to trans-Atlantic travel. When she was 2, the family had spent five years in France before returning to Boston, where the family had deep roots. She was young, beautiful, wealthy, and after the time she had spent more or less on her own in Paris was feeling rather independent. Like many another young woman of her time and place, she hadn’t attended college. But she was very definitely a seeker, a dreamer—a woman who wanted to find her own way in the world. In the attic of the house she and Sandy would eventually share in Roxbury, Connecticut, for much of their lives, there are still books she was reading before she met him, which include a volume of Proust’s great novel in the original French and another of Socratic dialogues.

Sandy Calder was just a few years older than Louisa. He was 5 feet 10 inches to her 5-foot-5. Although not conventionally handsome, he had always been attractive to women. A somewhat heavy man who was light on his feet, he had hazel eyes, a head of unruly hair and a big open face. He was funny and easygoing and appealing. Sandy’s unconventionality—he told Louisa he was a “wire sculptor,” which, not surprisingly, meant nothing to her—piqued the interest of this woman who herself had an unconventional streak, something she had inherited from her father. Calder put on his tuxedo in the evenings on the De Grasse, and he and Louisa danced, as he later recalled, rather violently, mostly to the tune “Chloe,” a song about a young man’s sentimental affection for his old mammy that Al Jolson had made famous. During the days they played deck tennis and watched the flying fish from the bow. There’s nothing like an ocean voyage to encourage a rapidly developing relationship. By the time they disembarked in New York, Sandy and Louisa were a couple. She was drawn to his energy, his intensity and his humor. And he was falling in love with her cool, contemplative spirit.

Calder: The Conquest of Time: The Early Years: 1898-1940

The first biography of America’s greatest twentieth-century sculptor, Alexander Calder: an authoritative and revelatory achievement, based on a wealth of letters and papers never before available, and written by one of our most renowned art critics.

Louisa James, as Calder soon realized, came from a family as artistically and intellectually distinguished as any in America. Although Louisa’s paternal grandfather, Robertson James, had never distinguished himself, his two oldest brothers were none other than William James, the great student of philosophy and psychology and the author of The Varieties of Religious Experience, and Henry James, known at the beginning of his career as Junior, before he began his ascent to near the pinnacle of novelists writing in English. Louisa’s father, Edward Holton James, was a man with progressive political ideas, who had been roughed up by the police during the Sacco and Vanzetti protests in Boston. An adventurous upbringing was something that Sandy and Louisa had in common. Both families had experienced life on the West Coast as well as the East Coast. Louisa’s parents, at the time Calder was getting to know her, lived in somewhat unconventional circumstances in Concord, sharing meals while inhabiting separate but adjacent houses.

The fact that Louisa’s family was well set financially couldn’t have been a matter of indifference to Calder. Despite his father’s fame as a sculptor, Calder’s family had never really achieved economic security—and with the crash of the stock market and the coming of the Depression, their situation seemed increasingly perilous. Over the winter of 1929-30, Louisa and one of her sisters, Mary, were living in New York, and Sandy and Louisa’s romance was deepening day by day. Louisa could see that Sandy’s talent, ambition and charm were unlocking more and more doors. For a young woman who, as her older daughter, Sandra, would remark many years later, had “wanted something different,” life with Sandy was very different—wonderfully different—from anything she’d known. That winter, Calder had exhibitions in New York and in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and mounted a number of performances of the Cirque Calder, but what mattered most during the eight months Sandy spent in the United States was his intensifying affair with Louisa.

And when he returned to Europe in March, Louisa wasn’t very far behind. She crossed the Atlantic again in July. She took a bicycle tour of Ireland with a friend, Helen Coolidge. And then, after a brief stay in London, she hotfooted it over to Paris—and to Sandy Calder.

When Louisa returned to the States in November, it seems that it still wasn’t entirely sure whether they were going to get married. However unconventional Louisa might have been, when confronting the question of marriage she was also very much a young woman from a fine Boston family, and aware of all the considerations that came with her place in the world. She certainly couldn’t overlook the fact that Sandy’s financial prospects were questionable at best. And yet she already sensed in him the powers of a man who would become one of the most extraordinary artists of the century. She wrote about this that November in a draft of a letter to her mother; we don’t know if it was actually mailed. “To me Sandy is a real person which seems to be a rare thing,” she announced. “He appreciates and enjoys the things in life that most people haven’t the sense even to notice. He has ideals, ambition, and plenty of common sense, with great ability. He has tremendous originality, imagination and humour which appeal to me very much and which make life colorful and worthwhile.” She told her mother that “he is getting impatient and I don’t see how I can keep him waiting, if I have definitely decided to get married.” And she concluded—“The thing that you must try and understand is that it can not drag on.”

**********

In October 1930 Calder gave a performance of his circus in Paris that was attended by some of the most demanding of the Parisian avant-garde, including the architect Le Corbusier and the painter Piet Mondrian. Not long after Mondrian’s visit to the Cirque Calder, Calder paid a visit to Mondrian’s studio at 16 rue du Départ.

************

Alexander Calder, 1898‑1976 Calder’s Circus, (1926‑1931)

From Calder’s Circus (1926‑1931). Wire, yarn, cloth, buttons, painted metal, wood, metal, leather and string, Dimensions variable Whitney Museum of American Art, New York;

Purchase, with funds from a public fundraising campaign in May 1982. One half the funds were contributed by the Robert Wood Johnson Jr. Charitable Trust. Additional major donations were given by The Lauder Foundation; the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc.; the Howard and Jean Lipman Foundation, Inc.; an anonymous donor; The T. M. Evans Foundation, Inc.; MacAndrews & Forbes Group, Incorporated; the DeWitt Wallace Fund, Inc.; Martin and Agneta Gruss; Anne Phillips; Mr. and Mrs. Laurance S. Rockefeller; the Simon Foundation, Inc.; Marylou Whitney; Bankers Trust Company Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth N. Dayton; Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz; Irvin and Kenneth Feld; Flora Whitney Miller.

More than 500 individuals from 26 states and abroad also contributed to the campaign.

************

(© 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

************

Alexander Calder, 1898‑1976 Calder’s Circus, (1926‑1931)

From Calder’s Circus (1926‑1931). Wire, yarn, cloth, buttons, painted metal, wood, metal, leather and string, Dimensions variable Whitney Museum of American Art, New York;

Purchase, with funds from a public fundraising campaign in May 1982. One half the funds were contributed by the Robert Wood Johnson Jr. Charitable Trust. Additional major donations were given by The Lauder Foundation; the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc.; the Howard and Jean Lipman Foundation, Inc.; an anonymous donor; The T. M. Evans Foundation, Inc.; MacAndrews & Forbes Group, Incorporated; the DeWitt Wallace Fund, Inc.; Martin and Agneta Gruss; Anne Phillips; Mr. and Mrs. Laurance S. Rockefeller; the Simon Foundation, Inc.; Marylou Whitney; Bankers Trust Company Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth N. Dayton; Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz; Irvin and Kenneth Feld; Flora Whitney Miller.

More than 500 individuals from 26 states and abroad also contributed to the campaign.

************

(© 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

************

Alexander Calder, 1898‑1976 Calder’s Circus, (1926‑1931)

From Calder’s Circus (1926‑1931). Wire, yarn, cloth, buttons, painted metal, wood, metal, leather and string, Dimensions variable Whitney Museum of American Art, New York;

Purchase, with funds from a public fundraising campaign in May 1982. One half the funds were contributed by the Robert Wood Johnson Jr. Charitable Trust. Additional major donations were given by The Lauder Foundation; the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc.; the Howard and Jean Lipman Foundation, Inc.; an anonymous donor; The T. M. Evans Foundation, Inc.; MacAndrews & Forbes Group, Incorporated; the DeWitt Wallace Fund, Inc.; Martin and Agneta Gruss; Anne Phillips; Mr. and Mrs. Laurance S. Rockefeller; the Simon Foundation, Inc.; Marylou Whitney; Bankers Trust Company Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth N. Dayton; Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz; Irvin and Kenneth Feld; Flora Whitney Miller.

More than 500 individuals from 26 states and abroad also contributed to the campaign.

************

(© 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

************

Alexander Calder, 1898‑1976 Calder’s Circus, (1926‑1931)

From Calder’s Circus (1926‑1931). Wire, yarn, cloth, buttons, painted metal, wood, metal, leather and string, Dimensions variable Whitney Museum of American Art, New York;

Purchase, with funds from a public fundraising campaign in May 1982. One half the funds were contributed by the Robert Wood Johnson Jr. Charitable Trust. Additional major donations were given by The Lauder Foundation; the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc.; the Howard and Jean Lipman Foundation, Inc.; an anonymous donor; The T. M. Evans Foundation, Inc.; MacAndrews & Forbes Group, Incorporated; the DeWitt Wallace Fund, Inc.; Martin and Agneta Gruss; Anne Phillips; Mr. and Mrs. Laurance S. Rockefeller; the Simon Foundation, Inc.; Marylou Whitney; Bankers Trust Company Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth N. Dayton; Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz; Irvin and Kenneth Feld; Flora Whitney Miller.

More than 500 individuals from 26 states and abroad also contributed to the campaign.

************

(© 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Mondrian was two years shy of 60 when Calder met him. His home—approached through a little courtyard off the boulevard Montparnasse—was unlike anything Calder had ever seen. The apartment had a curious setup, with the bedroom in one structure and the studio, irregularly shaped, a few steps up in what was a different but conjoined building. The studio was a five-sided room, with windows on two sides. The odd shape was part of its magic, the violation of the rectangular shape one would ordinarily have expected creating surprising spatial and visual dislocations.

Michel Seuphor, an artist and critic and Mondrian’s first biographer, recalled, like so many others, the shabbiness of the building and the shock upon coming from a dark entrance into the light-filled studio. “When you entered, it was still dark, but when you went through that second door [from the bedroom to the studio], when that opened, you went from hell to heaven. Beautiful! It was incredible.” Calder remembered that irregular space as “a very exciting room.” What struck Calder wasn’t so much the paintings—there weren’t many on display—but the light and the whiteness of the space, all the furniture painted white or black, the Victrola redone by Mondrian in red, and the broad back wall and the other walls with rectangles of various grays and colors arranged here and there. Calder wasn’t looking at paintings so much as he was walking into a painting. Standing in that astonishing studio, Calder at last understood where the increasing simplicity of his own wire sculpture had been leading him. It was much more than an understanding. It was a feeling. Calder could now see himself working in the abstract.

Mondrian’s studio was animated by the power of rectangles of primary colors to convey emotions and intensify experiences; he had been thinking and writing a great deal about architecture and how painting might finally expand and almost dissolve into architecture. Calder called these walls of rectangles Mondrian’s “experimental stunts with colored rectangles of cardboard tacked on.” He said, “It was hard to see the ‘art’ because everything partook of the art. Even the victrola had been painted so as to be in harmony. I must have missed a lot, because it was all one big decor, and the things in the foreground were lost against the things behind. But behind all was the wall running from one window to the other and at a certain spot Mondrian had tacked on it rectangles of the primary colors, and black, gray + white. In fact there were several whites, some shiny some matte.” Here abstract art became a visceral, wraparound experience.

Calder, imagining that there might be even more dynamic movement in the room, suggested to Mondrian “that perhaps it would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate.” Calder may have been thinking of attaching the colored shapes to motors, as he himself would do in some works over the next few years. But Mondrian, with what Calder recalled as “a very serious countenance,” replied, “No, it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast.” Mondrian was right. What Calder recalled as the “simplicity and exactitude” of Mondrian’s studio was in fact the vehicle for a propulsive power, a mysterious dynamism provoked not by the obvious mechanics of motors but by rectangles thrust into visually dynamic relations within his light-filled, five-sided room.

Calder sensed that dynamism, even if he didn’t yet fully understand it. As Calder later explained to a friend, Mondrian “told me to stick to primary colors; and I needed to know that. He told me he saw my line quiver. Mondrian loved Boogie Woogie music and he tried to put that on canvas.” It was these various kinds of speed that came together in Calder’s work of the next few years. Mondrian’s studio was Calder’s opening to the future.

“So now, at thirty-two”—so Calder put it in the Autobiography—“I wanted to paint and work in the abstract.” His first attempts were paintings rather than sculptures—perhaps a bow to Mondrian. These paintings are spare and enigmatic. Most of them—there are fewer than two dozen—don’t bring to mind specific works by Mondrian, in which the black lines extending from edge to edge assert the rectangle of the painting as a powerful, free-standing planar reality. Calder was already thinking about abstract forms as they moved through a fluid three-dimensional space. Calder later observed, “It was Mondrian who made me abstract—but I tried to paint, and it was my love of making plastic things that turned me to constructions.”

By “plastic,” Calder meant what Mondrian meant. He meant plasticity—the way forms could be shaped and reshaped to transform the space around them. So even as he was working on these first abstract paintings, Calder was beginning to contemplate a new kind of abstract sculpture—the sculptures that would emerge at the Galerie Percier in Paris scarcely six months later and establish him as one of the most radical artists of his time.

The visit to Mondrian’s studio was an experience that Calder would never forget. It was, Calder later wrote, “like the baby being slapped to make his lungs start working.” Mondrian didn’t make Calder a great abstract artist, but he awakened the possibility—he unleashed it. As Calder put it, Mondrian’s studio “gave me the shock that converted me.”

**********

Calder was becoming an abstract artist. But first he had to go back to America and marry Louisa James. Calder arrived back in New York just three days before Christmas, 1930. He had several works in an important show at the Museum of Modern Art, which was little more than a year old, but they were wooden sculptures of men and women and a cow that had been done a few years earlier and that gave no inkling of where his work was now moving. He spent a couple of happily busy holiday weeks in New York, where Calder’s parents were getting to know Louisa and her mother and her sisters; Louisa’s father was in India, working on a book attacking British colonial rule. To Calder’s sister, Peggy, living in the Bay Area, Calder’s mother wrote as full a description as she could muster of the woman who was soon to be her daughter-in-law. She described her as “athletic somewhat—fair—blue eyes—bushy brownish hair.” And she went on to say that Louisa “is neither shy nor bold nor merry, but loves Sandy’s jokes + Sandy’s mauling—has I think a clear head.”

The wedding was up in Massachusetts, at Louisa’s parents place in Concord on January 17, 1931. Sandy had mounted a performance of the Cirque Calder the night before, and when the minister apologized for having missed it, Sandy responded, “But you are here for the circus, today.” The glorious circus of Sandy and Louisa’s life would go on for 45 years.

By the last days of January, Sandy and Louisa were on the SS American Farmer, headed for France, less than two years after they had met on a ship headed for the States. Writing to her new in-laws, Louisa observed that Sandy was having two or three helpings of pie at dinner and growing “visibly stouter.” They were reading Moby-Dick together. As they got near England, Calder spent several hours one night watching “the lighthouses, and the lights of the other ships, and the men crawling up the ladder into the crows nest.” It was a tranquil journey. “So far our married life has run smoothly,” Louisa told her in-laws. “No storms at sea it must be a good omen.”

**********

A few months later, now established in Paris with his beautiful wife, Louisa, Calder emerged at the Galerie Percier as one of the most daring abstract artists of his generation. Calder’s sister, Peggy, writing many years later, speculated that “Louisa’s inheritance, along with wedding checks from friends and relatives, now made it possible for Sandy to experiment freely.”

But there was something more—something about the force of Louisa’s love that I believe powered his new work. There was a quietness, a contemplativeness about the lissome Bostonian who became Calder’s wife. She was, as he told a friend, a philosopher. And if Mondrian had given Calder the slap that had awoken him as an abstract artist, Louisa had given him the love that nurtured his contemplative, philosophical side.

Together Sandy and Louisa would embrace the coming decades—a world war, a growing family, a dazzling international fame—with the intrepid, idealistic spirit of the bohemian optimists who had first set up house together in Paris in 1931.

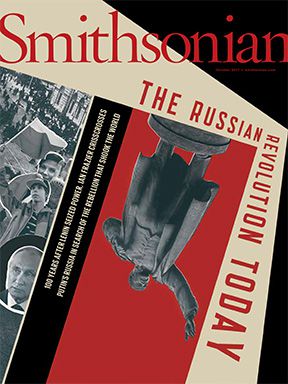

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $12

This article is a selection from the October issue of Smithsonian magazine