Though August 17, National Thrift Shop Day, is intended as a lighthearted celebration of an acceptable commercial habit, the process of making thrift stores hip involved unusual advocates. As I describe in my recent book From Goodwill to Grunge, thrift stores emerged in the late 19th century when Christian-run organizations adopted new models of philanthropy (and helped rehab the image of secondhand stores by dubbing their junk shops “thrift stores”).

Today, there are more than 25,000 resale stores in America. Celebrities often boast of their secondhand scores, while musicians have praised used goods in songs like Fanny Brice’s 1923 hit “Second-Hand Rose” and Macklemore and Ryan’s 2013 chart-topper “Thrift Shop.”

Yet over the past 100 years, visual artists probably deserve the most credit for thrift shopping’s place in the cultural milieu.

Glory in the discarded

From sculptor Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 ready-made urinal to “pope of trash” film director John Waters‘ popularization of a trash aesthetic, visual artists have long sought out secondhand goods for creative inspiration, while also using them to critique capitalist ideas.

During World War I, avant-garde artists started using discarded objects—stolen or gleaned, or purchased at flea markets and thrift stores—to push back against the growing commercialization of art. André Breton, Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst were among the first to transform cast-aside objects directly into works of art know as “readymades” or “found objects,” or to channel inspiration from such goods into their paintings and writings.

Coinciding with (and emerging from) the anti-art art movement Dada, which fiercely rejected the logic and aestheticism of capitalism, the movement surrounding that elevation of pre-owned items would soon have a name: Surrealism.

In his 1928 semi-autobiographical work “Nadja,” Breton, the “father of Surrealism,” describes secondhand shopping as a transcendent experience. Discarded objects, he wrote, were capable of revealing “flashes of light that would make you see, really see.” Exiled by the France’s Vichy government in the 1940s, Breton settled in New York City, where he sought to inspire other artists and writers by taking them to Lower Manhattan thrift stores and flea markets.

While Duchamp’s “Fountain” is perhaps the most well-known piece of sculptural art derived from a found object, his ready-made “Bicycle Wheel” (1913) appears even earlier. Man Ray’s “Gift” (1921) featured an everyday flatiron with a row of brass tacks secured to its surface.

While men did seem to dominate Surrealism, recent sources highlight the importance of the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, whom scholars suggest may have gifted Duchamp his famed urinal, making the “Fountain” collaboration. The eccentric and talented baroness created “God” (1917), a cast-iron metal plumbing trap turned upside down, the same year Duchamp displayed “Fountain.”

The trash aesthetic

Surrealism enjoyed its greatest renown throughout the 1920s and 1930s, with its precepts covering everything from poetry to fashion. Then, in the 1950s and 1960s, New York City witnessed the rise of an avant-garde trash aesthetic, which included discarded goods and the resurrection of bygone themes and characters from from the “golden age” of Hollywood film. The style became known as “camp.”

In the early 1960s, the Theatre of the Ridiculous, an underground, avant-garde genre of theater production, flourished in New York. Largely inspired by Surrealism, Ridiculous broke with dominant trends of naturalistic acting and realistic settings. Prominent elements included gender-bending parodies of classic themes and proudly gaudy stylization.

The genre notably relied on secondhand materials for costumes and sets. Actor, artist, photographer and underground filmmaker Jack Smith is seen as the “father of the style.” His work created and typified the Ridiculous sensibility, and he had a near-obsessive reliance on secondhand materials. As Smith once said, “Art is one big thrift shop.”

He’s probably best known for his sexually graphic 1963 film “Flaming Creatures.” Shocking censors with close-ups of flaccid penises and jiggling breasts, the film became ground zero in the anti-porn battles. Its surrealist displays of odd sexual interactions between men, women, transvestites and a hermaphrodite culminated in a drug-fueled orgy.

According to Smith, “Flaming Creatures” was met with disapproval not because of its sex acts, but because of its aesthetic of imperfection, including the use of old clothes. To Smith, the choice of torn, outdated clothing was a greater form of subversion than the absence of clothing.

As Susan Sontag points out in her famous assessment of camp, the genre isn’t merely a light, mocking sensibility. Rather, it’s a critique of what’s accepted and what isn’t. Smith’s work rebutted the reflexive habit of artists to strive for newness and novelty, and helped popularize a queer aesthetic that continued in bands like The New York Dolls and Nirvana. A long list of artists cite Smith as an inspiration, from Andy Warhol and Patti Smith to Lou Reed and David Lynch.

Beglittered rebellion

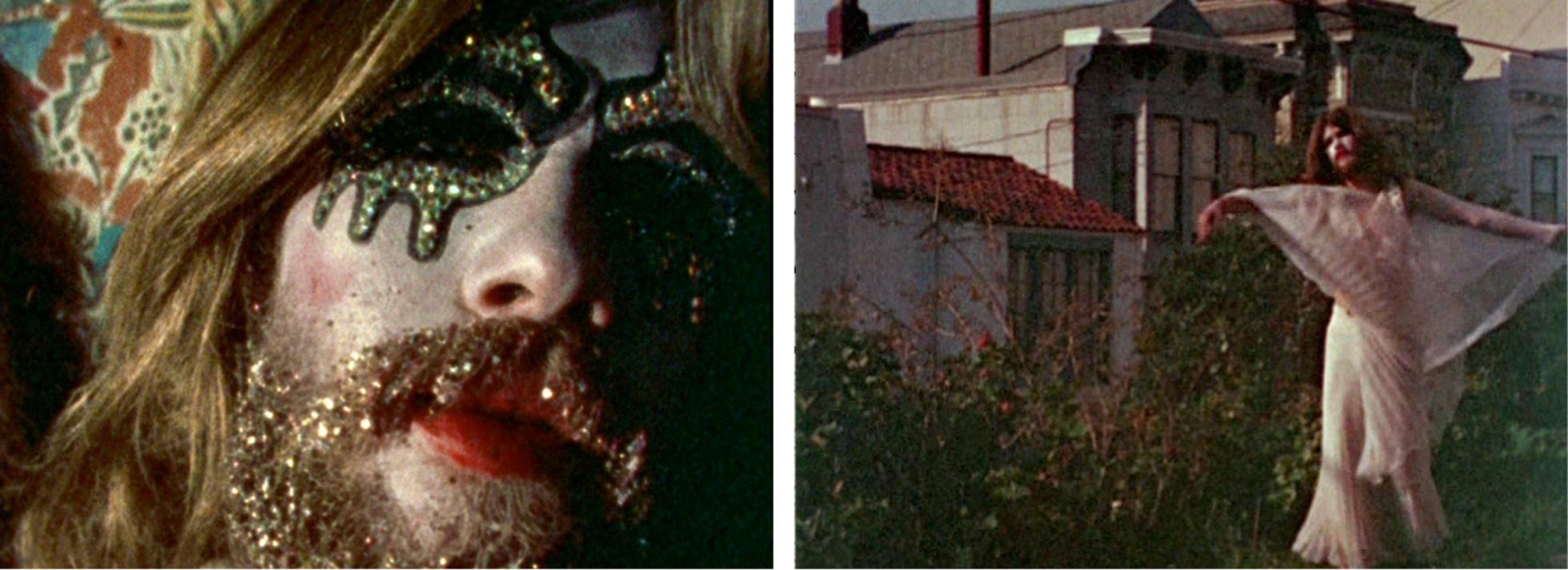

In 1969, items from Smith’s enormous cache of secondhand items, including gowns from the 1920s and piles of boas, found their ways into the wardrobes of a San Francisco psychedelic drag troupe, the Cockettes. The group enjoyed a year of wild popularity—even scoring a much-anticipated New York City showing—as much for their thrifted costuming as for their quirky satirical productions. The term “genderfuck” came to signify the group’s aesthetic of bearded men, beglittered and begowned, a style encapsulated by the Cockettes’ storied leader, Hibiscus.

The Cockettes split the next year over a dispute about charging admission, but members continued to influence American culture and style. Former Cockettes member Sylvester would become a disco star, and one of the first openly gay top-billing musicians. A later Cockettes member, Divine, became John Waters’ acclaimed muse, starring in a string of “trash films”—including “Hairspray,” which grossed US$8 million domestically—that very nearly took Ridiculous theater mainstream. By then, a queer, trash aesthetic that relied on secondhand goods became a symbol of rebellion and an expression of creativity for countless middle-class kids.

For many today, thrift shopping is a hobby. For some, it’s a vehicle to disrupt oppressive ideas about gender and sexuality. And for others, thrifting is a way to reuse and recycle, a way to subtly subvert mainstream capitalism (though some mammoth thrift chains with controversial labor practices tend to reap the greatest monetary benefits). Leading the charge, artists have connected secondhand wares with individual creativity and commercial disdain. What started with the surrealists continues today with the hipsters, vintage lovers and grad students who celebrate the outré options and cost-saving potential of discarded goods.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Jennifer Le Zotte, Assistant Professor of Material Culture and History, University of North Carolina Wilmington