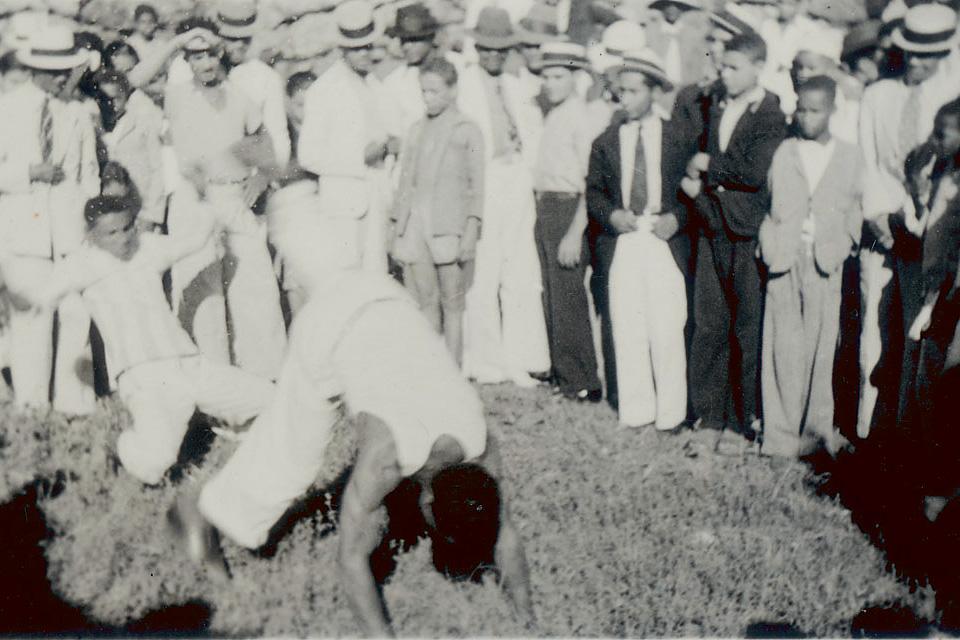

Two young men dressed in white kneel on the ground, ready to begin their duel. Eyes lock onto those of his opponent. Hearts beat faster. Ancestral sounds echo forth from the berimbau, a single-stringed bow-shaped instrument. Only then do the two shake hands, and the match may commence. With a dynamic, animal-like force, the two exchange movements of attack and defense in a constant flow of exploring and exploiting each other’s strengths and weaknesses, fears and fatigues. They wait and watch patiently for that careless moment in which to drive home a decisive blow.

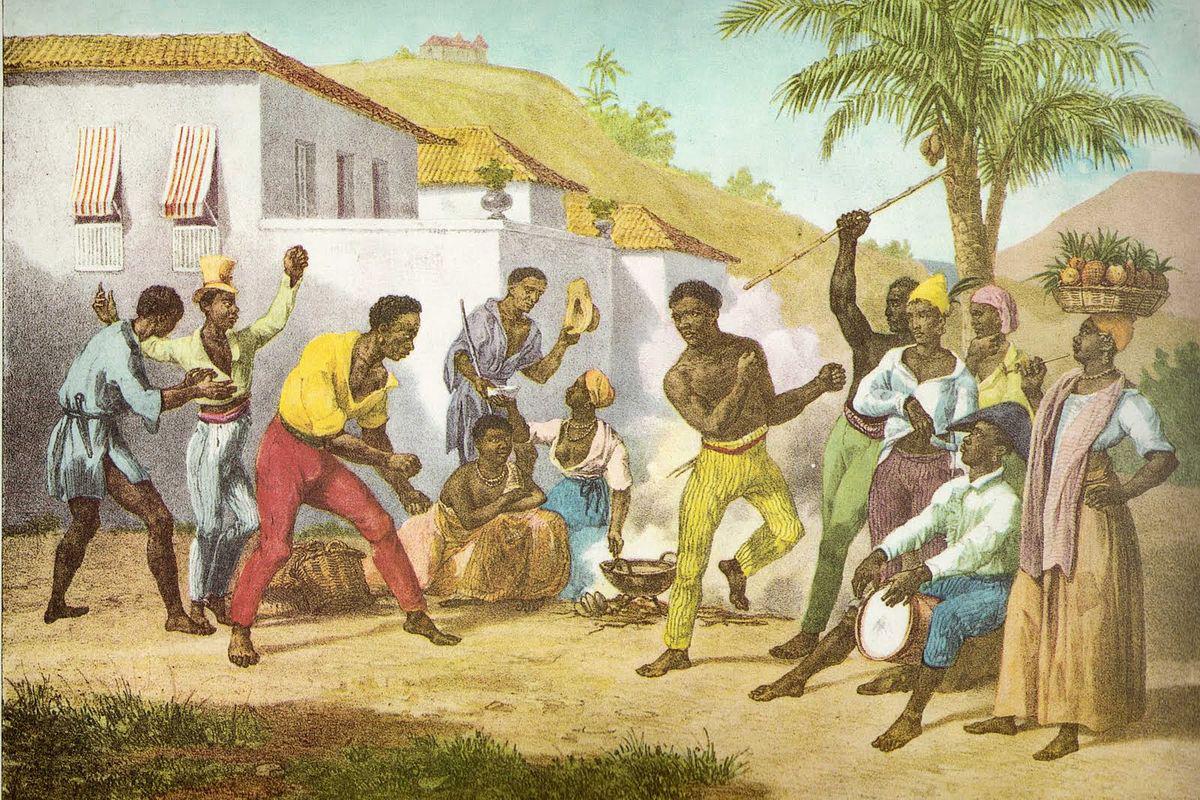

Capoeira developed in Brazil, derived from traditions brought across the Atlantic Ocean by enslaved Africans and fueled by the burning desire for freedom. It soon became widely practiced on the plantations as a means of breaking the bonds of slavery, both physically and mentally. During this time, the art was considered a social infirmity and officially prohibited by the Brazilian Penal Code. The identification of “the outlaw” with capoeira was so widespread that the word became a synonym for “bum,” “bandit,” and “thief.” However, that did not stop the capoeiristas from practicing. They moved to marginal places and camouflaged the martial art as a form of dance.

Today, we find people all over the world practicing capoeira, not only in parks and studios but also universities and professional institutions. It took a central role at this year’s Smithsonian Folklife Festival, where the On the Move program explored the journeys people take to and within the United States and the cultures, stories and experiences they carry with them. Capoeira is a result of the phenomenon of people migrating to new lands. As Mestre Jelon Vieira explained during the Festival, “Capoeira was conceived in Africa and born in Brazil.”

The Tradition: Resistance and Resilience

Between 1500 and 1815, Brazil was a colony of the Portuguese Crown—an empire sustained by slave labor. The business of capturing and selling humans brought enormous wealth to the Portuguese Crown, but it brought huge numbers of enslaved Africans to the New World. Hundreds of people were packed into overcrowded, infected holds of slave ships in order to maximize profit. As a result of the perilous and unhealthy conditions during the three-month journey, more than half of the enslaved lost their lives, their limp bodies tossed overboard.

Upon arrival, they were sold at the Sunday market and sent to work in the hot, humid and harsh conditions of the plantations, where many would be worked to death. The high mortality rates among the enslaved populations in Brazil, along with an increased demand for Brazilian raw materials like sugar, gold and diamonds, spurred the importation of growing numbers of Africans. An estimated four million enslaved people were shipped to Brazil until the mid-19th century.

The enslaved resisted in various forms: armed revolt, poisoning their owners, abortion and escape. The vastness of the Brazilian inlands made it possible for individuals on the run to hide. Some escaped and formed clandestine communities in the backlands of the rainforest, independent villages known as quilombos. Here, the Africans and their descendants developed an autonomous socio-cultural system in which they could sustain various expressions of African culture. Historians surmise that capoeira emerged from these communities as a means for defense under the oppressive Portuguese regime.

By the mid-1800s, the towns and cities of Brazil experienced an unprecedented urbanization. Cities grew in population but lacked adequate economic planning and infrastructure, resulting in a growing population of vagrants. The Paraguayan War between 1864 and 1870 brought a flood of veterans and refugees from destroyed quilombos into the cities. These people were attracted to capoeira not only for its sport and play but also for its powerful means of attack and defense for their survival.

Capoeira became a widespread practice at the beginning of the 20th century—outlaws, bodyguards and mercenaries used it. Even some politicians practiced as a way to sway constituents. In this time, strong social pressure throughout the country slowly transformed capoeira into a less aggressive weekend pastime. Eventually capoeiristas were meeting in front of bars, playing an apparently inoffensive kind of dance accompanied by berimbaus.

The oppression of capoeira diminished significantly during the 1930s. During this time, a particular mestre—or master—had been working toward restoring the dignity and historical perspective of the capoeira of his time. Mestre Bimba was born in 1899 in Bahia, in northwestern Brazil. In 1932 he became the first master to open a formal capoeira school called Luta Regional. By 1937, the school received official recognition by the government. The course of capoeira had changed.

Mestre Bimba established a disciplined method of teaching and legitimized capoeira as a form of self-defense and athletics. He developed a style called capoeira regional, which emphasized the technicality of movements and a dance-like nature. When he was summoned by the government to perform in front of distinguished guests, Mestre Bimba became the first to publicly present capoeira as an official cultural practice.

Capoeira on the Move

Mestre Bimba’s success sparked the growth of new schools in Bahia. As capoeira received more and more public affirmation, the younger mestres found better environments for new expression. Many of them left Bahia to teach in places like Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, taking the opportunity to develop their own styles. Contemporary capoeira was distinguished by its emphasis on cleanliness and articulation, a paramount fighting technique but also an innovative, spectacular visual show.

The 1960s marked a major turning point for the tradition. In 1964, Mestre Acordeon created the Grupo Folclórico da Bahia to share capoeira in a more organized and formal way. He and his group toured the country, reached into local schools, and won recognition in international competitions. Soon after, he founded the World Capoeira Association with the goals of promoting exchange through workshops, educational trips, and publications, and codifying a body of rules for the understanding and respect for the history, rituals, traditions and philosophy.

In 1972, the Brazilian government recognized capoeira as on official sport. The regulations laid down rules, definitions, bylaws, a code of ethics, recognized movements and a graded classification chart for students. It also established rhythms for the music and guidelines for the role of the berimbaus during competition.

This institutionalization and systemization of capoeira did not sit well with many mestres. They were opposed to such formalizing efforts, which they saw as an attempt to remove the art from its more organic, grassroots environment. Despite their opposition, capoeira was already engaged in a tremendous process of adapting to a changing society.

Capoeira was growing, spreading to different parts of Brazil and soon around the world. It took root in the United States in the mid-1970s when Mestre Jelon Vieira and Mestre João Grande introduced their art to new audiences. Since then, these two influential masters have dedicated their lives to growing a community of capoeiristas.

Mestre Jelon Vieira was born in 1953 in Bahia, Brazil. He moved to New York City in 1975 and planted the first seeds of capoeira in the United States. Aside from touring the country, the Caribbean, and Europe with his company, DanceBrazil, Vieira has been teaching in under-resourced communities and at institutions of higher learning such as Columbia University, Yale, Harvard and New York University. He is sure to immerse his students not only in the techniques of capoeira but also in the philosophy. Many people suggest that Mestre Jelon may be responsible for the incorporation of capoeira movements into modern-day breakdancing.

Encouraged by Mestre Jelon, Mestre João Grande, also from Bahia, founded his own academy in New York City in 1990, where he has trained thousands of students in the tradition of capoeiraAngola. Both men have been recognized for their mastery and commitment to passing on their traditions of capoeira with the National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship, our nation’s highest honor in folk and traditional arts.

Mestre Jelon and Mestre João Grande, at the Folklife Festival, explained his inspiration and how he first learned capoeira.

“I looked everywhere to learn capoeira,” he said. “When I couldn’t find capoeira, I started to observe nature—how the animals survive, how they fly, how they hunt, how the animals behave, how the fish swim, how they fight in the water, how the birds fly and never touch each other, how the wind hits the trees, how the trees move then become still again, how the snake moves on the ground, how the dogs play with humans and each other, how the hurricane turns.

“That is what inspired me—nature. Capoeira is nature.”

Juan Goncalves-Borrega is a curatorial intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage working with the 2017 On the Move program. He is pursuing a bachelor of arts in history and a bachelor of science in anthropology at Virginia Commonwealth University. A version of this article originally appeared on the Festival Blog, produced by the Smithsonian’s Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.