When news started coming in about the catastrophic damage Hurricane Irma brought to the Caribbean last month, I was working with archival materials dating back almost 30 years ago to the 1990 Smithsonian Folklife Festival’s program that focused on the U.S. Virgin Islands. In going through those boxes, I felt odd reverberations.

The year before, in the midst of the preparation for that festival, on September 17, 1989, Hugo struck the U.S. Virgin Islands as a category 4 force hurricane, with the greatest damage occurring in St. Croix. A Washington Post special report said: “Not only was Christiansted strewn with uprooted trees, broken utility poles, shattered cars and tons of debris from buildings that looked bombed, but the verdant tropical island suddenly had turned brown. So strong were Hugo’s winds that most trees still standing were shorn of leaves.” While St. Croix suffered the brunt of the storm, St. Thomas and St. John were also significantly damaged.

Just as Irma and Maria have, Hugo also caused widespread damage in the Leeward Islands and in Puerto Rico.

We wondered if we should cancel or defer the Festival program to let the region recuperate, physically and financially. But our partners in the Virgin Islands responded with one voice: now, more than ever, the people of the Virgin Islands told us that they needed a cultural event to raise their spirits, and to remind them of their resilience, and to tell the world they were recovering. It is particularly in times of disaster that people turn to culture not only for solace but for survival.

“The recent disaster of Hurricane Hugo made fieldwork a little more difficult than usual,” reported curator Mary Jane Soule in one of the documents in the box. Soule was doing research on musicians in St. Croix. “I was unable to rent a car for the first five days I was there, which limited my mobility. Many phones were still not working, so getting in touch with informants was harder than usual. However, once I actually located the individuals I wanted to see, I found most of them willing to talk,” her report said.

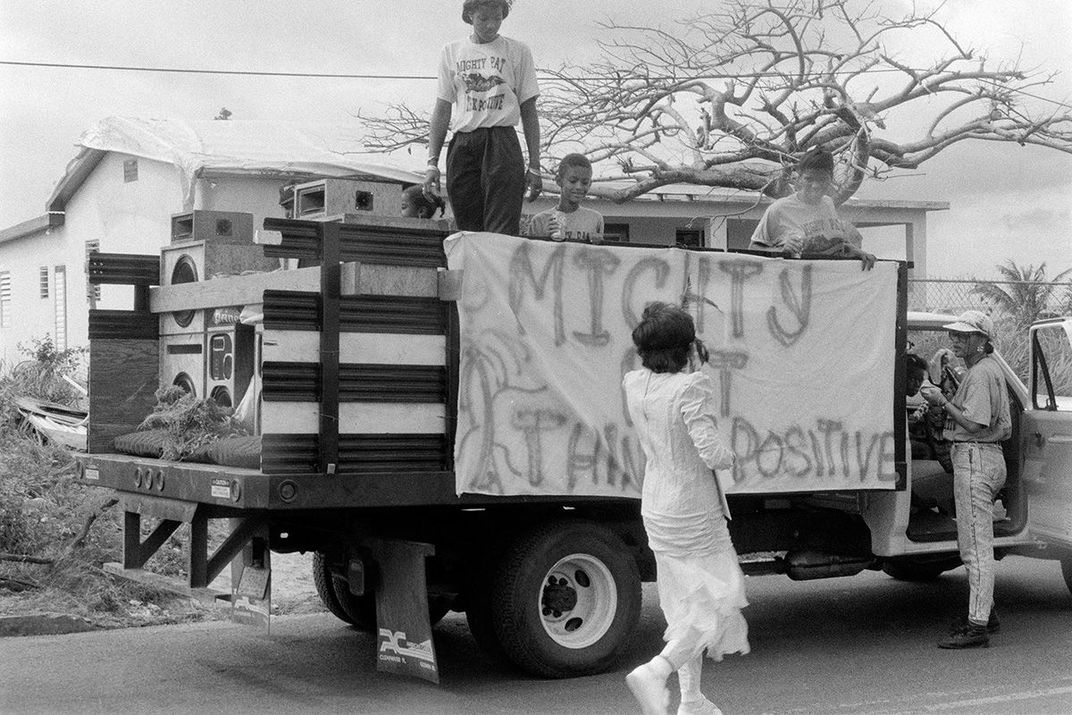

A local press announced that, regardless of the circumstances, the Three Kings Day Parade would not be canceled: “Neither rain [n]or hurricane nor winds nor controversy will stop the Crucian Christmas Fiesta.” In her field research tape log, Soule lists the role of Hugo in the fiesta, adding that calypso bands had recorded songs about it.

“Eve’s Garden troop is depicting Hugo,” Soule wrote. “The No Nonsense (music and dance) troop is doing ‘The Hugo Family’ depicting the looting and tourists on the run. Mighty Pat’s song ‘Hurricane Hugo’ played from speakers on one of the numerous trucks. Sound Effex (band) can be heard playing ‘Hugo Gi Yo’(Hugo Gives You).”

Several months later when staff returned to the islands, “Hugo Gi Yo” was still very popular, as were the black, monographed sailors’ caps that proclaimed “Stress Free Recovery for 1990, St. Thomas, V.I.”

Songs about Hugo relieved anxiety. Many people had lost everything. But like all good calypso tunes, they comically contributed to the oral history of the islands.

Look at the verses of “Hugo Gi Yo”:

It was the seventeenth of September 1989 Hugo take over.

Hey, that hurricane was a big surprise,

When it hit St. Croix from the southeast side.

Hey rantanantantan man the roof fall down.

Rantanantantan galvanize around…

No water, no power, no telephone a ring.

We people we dead; there’s nothing to drink….

Calypso songs are noted for their social commentary on events as well as on responses from mainstream society. The Washington Post report on St. Croix continued: “The plunder started on the day after the Sunday night storm, as panicky islanders sought to stock up on food. It quickly degenerated into a free-for-all grab of all sorts of consumer goods that some witnesses likened to a ‘feeding frenzy.’ Three days of near-anarchy followed Hugo’s terrible passage during the night of Sept. 17-18 and prompted President Bush to dispatch about 1,100 Army military police and 170 federal law-enforcement officers, including 75 FBI and a ‘special operations group’ of U.S. Marshalls Service.”

In turn, “Hugo Gi Yo” responds:

You no broke nothing.

You no thief nothing.

You no take nothing.

Hugo give you.

As program research advisor Gilbert Sprauve explained, calypsonians “lend themselves heartily to expressing the underclass’s frustrations and cynicism. They make their mark with lyrics that strike at the heart of the system’s dual standards.”

Soule transcribed existing racial and economic tensions in St. Croix expressed in Mighty Pat’s “Hurricane Hugo”:

After the hurricane pass, people telling me to sing a song quickly.

Sing about the looting, sing about the thiefing, black and white people doing.

Sing about them Arabs, up on the Plaza rooftop

With grenade and gun, threaten to shoot the old and the young.Curfew a big problem, impose on only a few, poor people like me and you.

Rich man roaming nightly, poor man stop by army, getting bust__________

Brutality by marshal, send some to hospital,

Some break down you door, shoot down and plenty more.When I looked around and saw the condition

of our Virgin Island.

I tell myself advantage can’t done.

One day you rich. Next day you poor.

One day you up the ladder. Next day you

crawling on the floor.

Beauty is skin deep; material things is for a time.

A corrupted soul will find no peace of mind

I think that is all our gale Hugo was trying to say

to all mankind.

Don’t blame me. Hugo did that.

Hurricane Hugo also came up in conversations about craft. Knowing the importance of charcoal making, especially in St. Croix, researcher Cassandra Dunn interviewed Gabriel Whitney St. Jules who had been making coal for at least 40 years and was teaching his son the tradition. In Dunn’s summary report, thoughts of the hurricane are not far away.

“Cooking food by burning charcoal in a coal pot is a technique utilized in the West Indies and Caribbean from the mid-1800s,” she wrote. “Charcoal makers learned the techniques of using a wide variety of woods including that from mango, tibet, mahogany and saman trees. After Hurricane Hugo, those in St. Croix who had lost access to gas or electricity reverted to charcoal and the coal pot.”

With similar stories from St. Thomas, it became clear that this quotidian cultural artifact that reconnected islanders with their heritage served as an essential item for survival with dignity. The image of the coal pot became central to the themes of the Festival program, both as a useful utensil and a symbol of resilience.

To our surprise, the coal pot, which looks much like a cast iron Dutch oven, was identical to that used by participants in the Senegal program featured that same year and led to increased cultural interaction between the two groups. This prompted a re-staging of both programs in St. Croix a year later.

The cultural responses to Hurricane Hugo and those I suspect we’ll see following the calamitous hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria remind us that when disaster strikes, whether natural, social, political or economic, communities often turn to shared cultural resources. Stories, experiences, and traditional skills prove useful, inspiring us to overcome obstacles and help our communities regain their footing.

A version of this article originally appeared in the online magazine of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. Olivia Cadaval was the program curator for the U.S. Virgin Islands program at the 1990 Folklife Festival and is currently a curator and chair of cultural research and education at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. Audio recorded by Mary Jane Soule and mastered by Dave Walker.