On Pete Souza’s Instagram, it’s almost as if Barack Obama is still president. The former chief official White House photographer, who shot up to 1,000 pictures a day over the eight years of the Obama administration, has plenty of material to share. Since January 20, he’s been going through his seemingly endless stream of images, satiating his nostalgic audience of 1.6 million followers—and sometimes offering a sly contrast with the optics of the current administration.

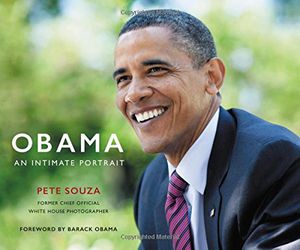

Souza selected more than 300 photographs for his new book, Obama: An Intimate Portrait (Little, Brown and Company), released this month. It’s a comprehensive look, starting with the moments before the 2009 inauguration, as President Obama reflects in the mirror before heading out to the stage, to his departure following Trump’s inaugural morning, as Obama gazes down at the White House through his helicopter window. In the foreword, the former president admits “I probably spent more time with Pete Souza than with anybody other than my family.” Souza, whose book tour is selling out from Los Angeles to London, will be speaking at the National Museum of African American History and Culture on November 20.

The Smithsonian Institution has entered affiliate agreements with the companies listed in our holiday shop, and earns a fee for every purchase made from following any link from these gift guide pages and making a purchase on the affiliate site. This fee helps fund Smithsonian’s activities.

All products on the Smithsonian.com Store are sold through affiliates. All returns, defects, or inquiries about products should be directed to the affiliate. The Smithsonian is not responsible for and has no control over affiliate transactions. Please note that these vendors operate independently of the Smithsonian and may have their own privacy policies. When you visit their websites, you leave our Website and no longer will be subject to our privacy and security policies. The Smithsonian is not responsible for the privacy or security practices or the content of other sites, and such links are not intended to be an endorsement of those sites or their content.

Originally from Massachusetts, Souza studied communications at Boston University and Kansas State University. He served as an official photographer in President Reagan’s White House, and later, in 2005, as the national photographer for the Chicago Tribune, met Obama, when the future president was a newly elected senator from Illinois. Souza published The Rise of Barack Obama in 2008, chronicling the politician’s first days as senator to presidential primaries. In the years since first meeting, they’ve developed an obvious trust, one that enabled the photographer to so thoroughly capture the dynamics and legacy of the Obama presidency.

Many of the photos are familiar. There is the one of administration officials in the Situation Room watching the raid on the Osama Bin Laden compound, the elevator ride with the President and the First Lady sharing an intimate moment on their way to an inaugural ball in 2009 and the President flexing his muscles with a young trick-or-treating superman in the halls of the White House. But a number of lesser-known images are a reminder of the unique access Souza was granted as he documented midnight meetings with foreign leaders and covert helicopter rides.

Since John F. Kennedy, each president, save Carter, has had an official photographer. Some have been able to get up close and personal, like David Hume Kennerly who documented the Ford administration and was treated like a close friend, while others were kept at a distance. Nixon unsurprisingly shied away from his photographer, Oliver F. “Ollie” Atkins, whose most famous image is a meet-and-greet between Nixon and Elvis. The first photographer to have worked in two administrations, Souza was also the first to fully embrace social media as a way to connect the president with the people.

In his introduction, Souza writes, “On paper, the job of Chief Official White House Photographer is to visually document the President for history. But what, and how much, you photograph depends on each individual photographer.” He continues, “It was my job to capture real moments for history. The highs and lows, the texture of each day, the things we didn’t even know would be important later on.” His book offers a chance to reflect on how the medium has shifted the public’s relationship with the office through history.

Before photography, disseminating the president’s likeness was a complicated process, explains David Ward, former senior historian of the National Portrait Gallery. Oil paintings became lithographs and woodcuts, often degraded with each reproduction. What started as a sophisticated piece of art could end up looking “like a third grader’s drawing of an egg,” joked Ward. But there was always a curiosity about the president and first family, starting with George Washington.

Representations of the president, Ward says, “definitely increased whatever tendencies there were for the kind of imperial president.” Through the increased visibility, the executive shifted from being one of three equal branches to the dominant one. As he points out, “we’ve got every president in the National Portrait Gallery but we don’t have every representative or even every chief justice.” The medium of photography, Ward posits, “made the office more powerful…[because] you’re seeing the President on the job all the time.”

Although President William Henry Harrison was the first to be photographed while in office, Abraham Lincoln was the first president to fully embrace the medium as a way to connect with his constituents. In his 1860 campaign, Lincoln distributed buttons with tintype photos of him and his running mate, Maine Senator Hannibal Hamlin. The reliance on photography continued even after his initial victory: during the Civil War, Lincoln was frequently photographed to show the country he was on duty. Historian Ted Widmer, who served as a speechwriter for President Bill Clinton, explains, “In the early months of his presidency, Lincoln more than tolerated his photographers; he intuitively understood that they were helping him a great deal as he tried to give the Union a face—his own.”

Following Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt was the next to truly embrace the medium. And he took the camera on the road, inviting photographers to document his time outdoors and his journey to Panama. By the time he entered office, reprinting photographs in newspapers was more commonplace. Combined with smaller and more portable cameras, the technology allowed for an easier distribution of the president’s photograph in papers around the country and the world.

It was Kennedy who appointed the first official chief White House photographer. Before his election, he relied on Jacques Lowe to photograph his personal life and campaign. When he became president, he hired Cecil Stoughton whose “unusual access to John F. Kennedy’s private life expanded the public’s view of the presidency,” writes Bijal Trivedi at National Geographic. “The pictures were pivotal in projecting the image of a youthful, dynamic President ushering in a new era in U.S. history.” The creation of the White House photographer position meant that Stoughton was aboard Air Force One after JFK’s assassination. He was responsible for getting the only photos of Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson being sworn in as president.

Ann Shumard, curator of photography at the National Portrait Gallery, sees a parallel between Souza’s and Stoughton’s images: they capture “affecting moments, such as when President Obama leaned down to allow a little boy to feel the hair on his head.” Souza’s book also includes photos of Obama playing with his daughters in the snow after a major storm and coaching Sasha’s basketball game, images that certainly echo some shots Stoughton grabbed of JFK with his children. Among Stoughton’s favorites is one of President Kennedy clapping while Caroline and John Jr. dance in the Oval Office. “He was doing fatherly things and the children [were] cavorting and competing for his attention. I snapped 12 frames,” Stoughton told National Geographic. “That afternoon the President flipped through the pictures and chose one to send to the press—it showed up in every metropolitan daily in the U.S. and around the world.”

Despite the similarity between the Kennedy and Obama photos, Souza writes in his book that President Johnson’s photographer, Yoichi Okamoto, was his inspiration: “Okamoto pushed the bar and photographed seemingly everything Johnson did.” During LBJ’s administration, Okamoto was granted Oval Office walk-in privileges after he made his case to the president: “Rather than just take portraits, I’d like to hang around and photograph history being made.” He dedicated some 16 hours a day to documenting the presidency, and in doing so set a high standard for the position and what it meant.

“The more access a White House photographer is given, the more complete his or her record will be,” says Shumard. The sheer number of images (just under 2 million in eight years for Souza) means that Obama’s is one of the most thoroughly photographed presidencies. “How meaningful or accurate that record proves to be can only be judged with the passage of time, when every image can be judged in light of what history tells us about the moment it documents,” says Shumard.

The White House photographer’s work can be seen in two ways. It at once promises transparency: the images convey a sense of immediacy and information. But the photographer’s image choices and the later selection of photos to share are in themselves a curation of the presidency, which either creates or reinforces a particular narrative.

While Obama may have the most photographed presidency, the wider press wasn’t necessarily part of that effort. In 2013, the White House Correspondents’ Association warned in a letter to the press secretary that the administration was limiting their access to cover newsworthy events. By claiming the opportunities were private, and then publicly releasing photographs through controlled channels, the White House was “blocking the public from having an independent view of important functions of the executive branch of government.” With President Trump, limited access for press and photographers has been a constant concern. But, unlike Obama, Trump’s even shied away from his appointed chief official photographer, Shealah Craighead, leaving his administration less documented.

Obama only left office in January and given the political upheaval since then, it’s not surprising how quickly nostalgia set in for his supporters. The curated Obama: An Intimate Portrait might be a welcome sight for their sore eyes, but the works of Souza’s photographs, forever held in the National Archives, will have value for years to come as a historical record.