A little more than a year ago, Jordan Bennett, an indigenous artist from the Canadian province of Newfoundland, was thinking about his next work. On a computer, he opened the online collections database of the Smithsonian Institution and typed in the words “Mi’kmaq”—the name of his own nation—and “Newfoundland.” A photograph appeared, and then a handful more, from negatives held by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. They had been shot by an anthropologist in the 1930s in a community a few hours away from Bennett’s own.

As he looked through them, the last name of one of the subjects suddenly caught his eye: Joe “Amite” Jeddore.

“I contacted my friend John Nicholas Jeddore,” Bennett remembers, “and he said, ‘That’s my great-great-uncle.’”

Intrigued, Bennett set out to revisit the photographs, and his experience led to one of nine artworks now on view in the new exhibition “Transformer: Native Art in Light and Sound” at the American Indian Museum’s George Gustav Heye Center in New York City.

Bennett sat down with the Jeddore family, and together they figured out exactly where the photographs, which showed Amite Jeddore preparing to go salmon fishing, had been taken. Bennett and his friend John Nicholas Jeddore recorded audio at each location, mostly sounds of the outdoors, with the occasional dog barking or people passing by. Then, through months of listening and tweaking, Bennett wove the recordings, along with the words of Mi’kmaq community members, into a multilayered digital soundscape.

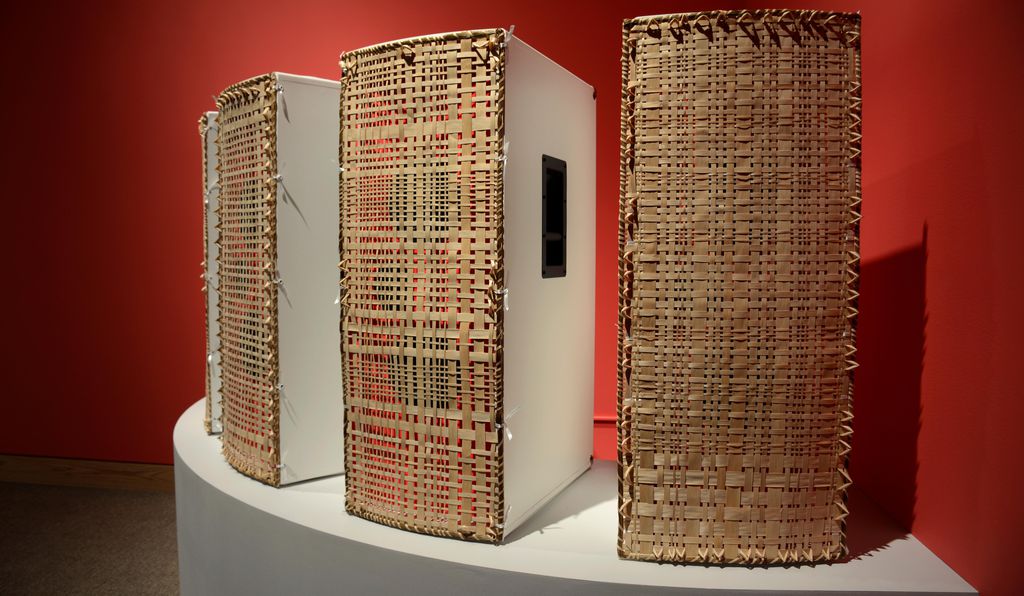

In the artwork, called Aosamia’jij—Too Much Too Little, this technologically sophisticated soundtrack now emerges from behind a mesh of traditional Mi’kmaq basketry. What Bennett calls his “hybrid basket-speakers” were a project in themselves. The artist spent two weeks in Nova Scotia with a cousin’s grandmother and great-aunt, learning split-ash basket weaving. He constructed the speakers, covered the fronts with his woven basketwork and trimmed them with sweet grass, which he says is not only a classic decorative finish on Mi’kmaq baskets, but also important to the Mi’kmaq both as medicine and “for spiritual purposes.” With these details, he says, “You’re adding a deeper part of yourself.” The finished work, he says, touches on “the family history of the Jeddores,” along with “my own learning, my own understanding of Mi’kmaq traditions.”

The anthropologist who took the photographs in 1931 probably thought “this was a dying culture,” the artist says. “I wanted to speak back to the memory of Amite, to let him know we’re still doing this work”— traditional salmon fishing as well as basket weaving. He adds, “I wanted to bridge the gap between what the Smithsonian had and what we have in Newfoundland.”

Bennett’s basketwork may be traditional, but many of the other works in “Transformer” bear few traces of indigenous craft. Instead, the thread connecting all the works in the show is that the artists “are working within contemporary media to tell an indigenous story,” says David Garneau, a co-curator of the exhibition and associate professor of visual arts at the University of Regina in Saskatchewan. Incorporating light or sound or both, the artworks range from digital portraits and videos to sound installations. They are powered by electricity, but they reflect traditional Native content.

In one sense, there’s nothing new about this balance between modern media and indigenous tradition. Whether it was European glass beads imported hundreds of years ago, or film and video in the 20th century, “Native artists have always picked up available technologies,” says Kathleen Ash-Milby, a co-curator of “Transformer.” Now, and especially in Canada, where government funding supports art, technology and indigenous artists in particular, Native artists are adopting digital media as well. (Six of the ten artists in the exhibition are from Canada, a fact both curators attribute to the stronger funding there. Garneau says simply, “There are many fewer artists working this way in the States.”)

In choosing works for the show, Ash-Milby says, they sought out artists who were taking the technology “in a very aesthetic direction,” that is, emphasizing color and form rather than, say, narrating history or combatting stereotypes.

Coincidentally—or not—these artists also turned out to be the same ones who “were really drawing on tradition in their work,” she says, adding later, “So much Native historical traditional expression was visually tied to form and design, it shouldn’t be surprising that this relationship continues.”

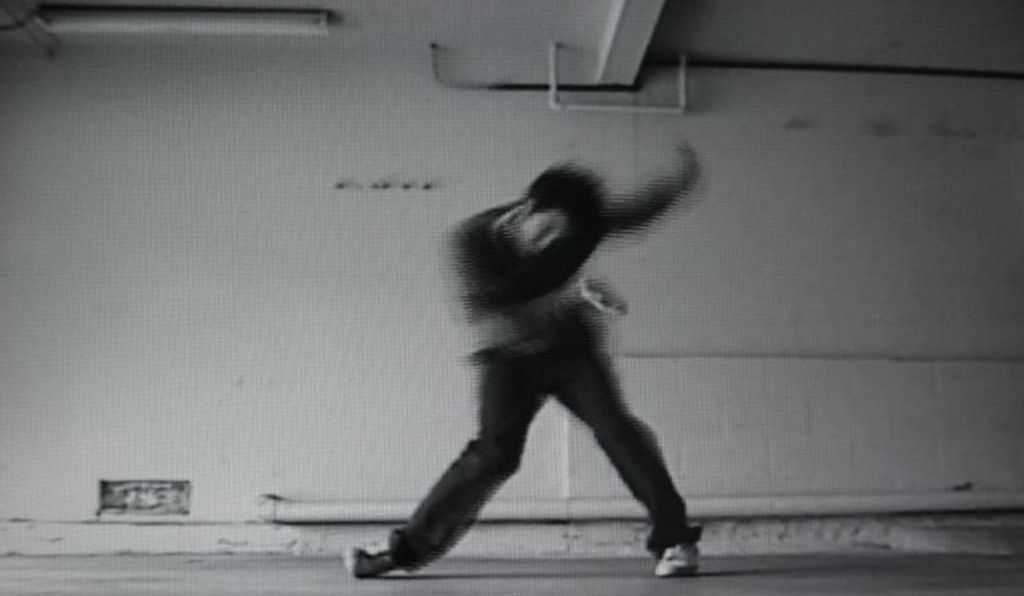

In Nicholas Galanin’s video Tsu Heidei Shugaxtutaan (We will again open this container of wisdom that has been left in our care), 1 and 2, Native and non-Native dancers switch roles, with the Peruvian-American doing a loose-limbed hip-hop improvisation to a traditional Tlingit song, and the Tlingit dancer performing a traditional dance to contemporary electronic music. In Stephen Foster’s Raven Brings the Light, an old Northwest Coast story is retold, obliquely, in recorded forest sounds and in light and shadow on the walls of a tent.

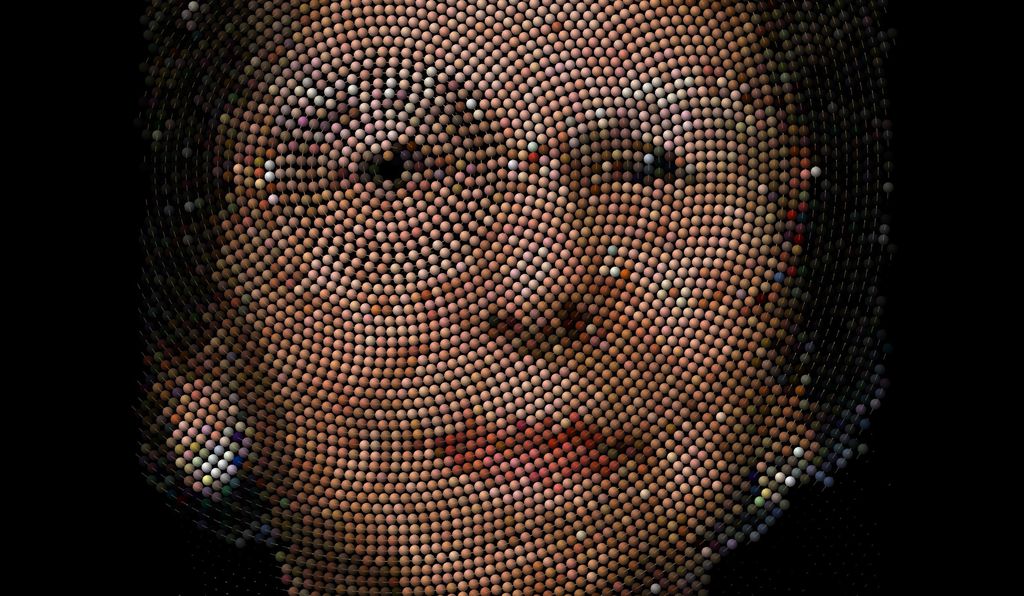

In the case of Jon Corbett’s Four Generations, tradition may be embedded in the pixels themselves. This series of family portraits is made up of digital images of beads arranged in a spiral on a screen, with faces slowly appearing and disappearing as beads are added and subtracted in a mesmerizing rhythm. Pixels on a computer screen are generally laid out in a grid, but Garneau says that the rectangular grid has an oppressive history as a tool of the European surveyors who broke up Native settlements in the 19th century. So instead, the artist has laid the beads out in a spiral, a more meaningful form in indigenous cultures. The work echoes Native beadwork, Garneau says, while finding a novel way “to get past the grid that is the screen.”

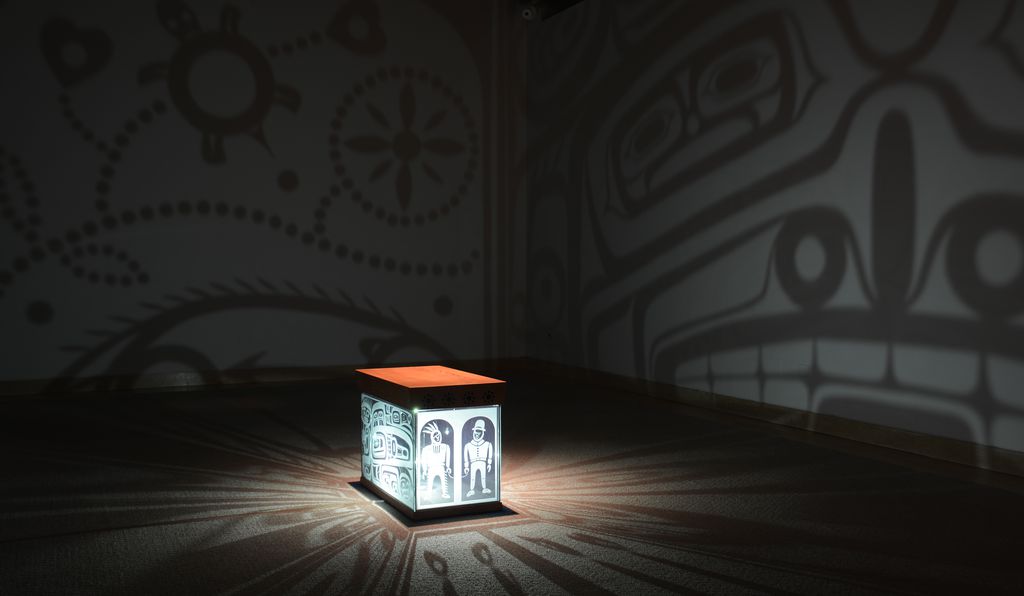

Marianne Nicolson’s The Harbinger of Catastrophe grapples with threats that are very much of the 21st century. Her home community, Kingcome Inlet, B.C., suffered disastrous river flooding in 2010. “The entire community was evacuated by helicopter,” she says. “We have been there for thousands of years, and there was no precedent for it.” She believes the flooding was the result of a century of commercial logging, which altered the river’s course, coupled with climate change, which is causing a glacier that feeds the river to melt. In her installation, Nicolson placed a moving light inside a glass chest in the style of a traditional Northwest Coast bentwood box, and the shadows it casts inch up the gallery walls like floodwaters.

In the box’s size and shape, its shell inlay and the figures on its sides, the work draws strongly on indigenous visual traditions of the Northwest Coast. But its references also spiral outward to include the artist’s ideas about the dangers of capitalism and climate change. Nicolson says she was inspired by the museum’s site in lower Manhattan, near Wall Street. On one end of the box, she portrays the Dutch purchase of Manhattan and the “exchange of money for land that the colonists made with indigenous people.” And the rising floodwaters that her piece evokes, she says, could just as well be those that inundated the museum’s neighborhood after Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

The work also includes an image of a turtle, an animal that is significant to many other Native cultures but not her own. “I wanted to open it up so it wasn’t just specific to my particular place in this land, but also all across North America,” she says. “My hope is that the teaching of the indigenous population”—in how to care for the land over the long run—“will be taken up by the wider culture. We have the solutions, if other people would not dismiss them.”

Like the other artists in “Transformer,” Nicolson is searching urgently for new ways to communicate age-old ideas. As Garneau says, “An artist who is indigenous faces this dilemma: Are they going to be a traditional person in their art,” by working strictly in traditional media like quilling or beading, for example? “Then they’re a contemporary person, but they’re not making contemporary art.”

“Some artists,” he says, “are trying to find a space in between.”

“Transformer: Native Art in Light and Sound” is on view in New York City at the National Museum of the American Indian, George Gustav Heye Center, through January 6, 2019.