A few years ago, some 21st-century digital housekeeping helped Karen Daly solve one of the 20th-century mysteries behind a 17th-century painting.

Daly, the registrar for exhibitions and coordinator of provenance research at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, was going through data files as the VMFA was getting ready to launch a new website, which would include a new system for managing museum records and databases.

She had been reviewing documents for items in the museum’s permanent collection and was intrigued by what she found for Battle on a Bridge, completed by Claude Lorrain (born Claude Gelée) in 1655. The painting depicts an idyllic scene of a shepherd, his family and flock on the move, with soldiers fighting and falling from a bridge close by and what look like war ships in the background harbor.

The VMFA purchased Battle on a Bridge in 1960 knowing a little bit about its past: The paperwork showed that the painting had been seized by Nazis during World War II, then returned to France after the war. The names and places in the documents led to as many questions as they answered: How did the painting end up in enemy hands? How far did it travel before it went home? And before the war, where did it come from?

Only in the last five years or so have shared online resources become available to help art researchers find the missing pieces of the provenance puzzle. To make it easier for those in the U.S. and in Germany to trace the history of these artworks together, the Smithsonian Provenance Research Initiative and Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation created the German/American Provenance Research Exchange Program for Museum Professionals (PREP). Curators, historians, collections managers, legal experts and technologists will meet September 24 to 29 in Berlin for a series of discussions and on-site workshops in Berlin’s museums, archives and galleries.

Daly participated in the first PREP meeting, in New York in February, and will attend the Berlin gathering. Ever since she found a clue to Battle on a Bridge on a German website, she’s been eager to share what she’s learned about the painting’s past. That clue—a number—led her to a man in Nazi Germany’s exclusive and shadowy cultural circles.

“Karl Haberstock was involved in taking the painting,” says Daly. “He was Hitler’s art dealer.” Haberstock was responsible for determining which plundered artworks he could sell to help finance the government. These included approximately 16,000 objects of “degenerate art” removed from German museums between 1933 and 1938, art confiscated in newly annexed Austria and Poland and art from “Aryanized” firms.

Starting in 1938, the Nazis strong-armed Jewish property and business owners into selling their assets, including artworks and art galleries, to non-Jews, under the “Aryanization” policy. Some Jewish collectors sold their holdings to fund their escape from Germany. Dealers with questionable scruples, like Haberstock, stepped into the art marketplace to take advantage of fleeing families and Nazi allies who remained.

With a network of German agents and French collaborators, Haberstock looted art from France, Holland, Belgium, Switzerland and Italy. He acquired Battle on a Bridge from the Wildenstein & Cie gallery in Paris in June 1941. The VMFA knew the painting had been restituted to the Wildenstein family sometime after the war, so Daly hoped that the number she saw on that German website might help fill in the painting’s timeline.

“This is a painting that’s often in our galleries, so I had to take it off-view” to see if the number appeared on the back of the painting. Daly found what she was looking for: Linz Label No. 2207. That number signified that “this painting was part of the inventory that the Nazis kept of the items for the museum”—the “Linz collection” of art for the “Führermuseum,” Hitler’s monument to the Aryan race.

Planned for his childhood hometown of Linz, Austria, Hitler envisioned a cultural district that would help Linz grow to culturally rival Vienna. The Führermuseum would sit at heart of the district, filled with artwork celebrating such “German virtues” as industry and self-sacrifice.

After Haberstock added Battle on a Bridge to the growing Linz collection, the painting’s trail went cold for four years. Where, exactly, did it go?

During the war’s final months in Europe, a baron and fellow Nazi-connected art dealer invited Haberstock to hide out at his castle in the northern Bavarian village of Aschbach. Several months later, in spring 1945, Allied troops found Haberstock, another colleague and their respective art collections at the castle. Haberstock was taken into custody, and the works he had with him were impounded.

Meanwhile, the Nazis had hidden the bulk of the Linz collection, including Battle on a Bridge, in a salt mine at Altaussee, in the Austrian Alps. The Allies’ “Monuments Men” (and women) moved thousands of works from the mine to a collection point in Munich, and Battle on a Bridge was restituted to France in 1946.

“We have documentation that it was recovered by the Allies” before the VMFA purchased it, Daly says, “but did it ever go to Berlin? It’s exciting to confirm some of the locations on the map, if you will, of where we know it went.” (Since the Führermuseum was never built, the painting likely spent little, if any, time in Linz.)

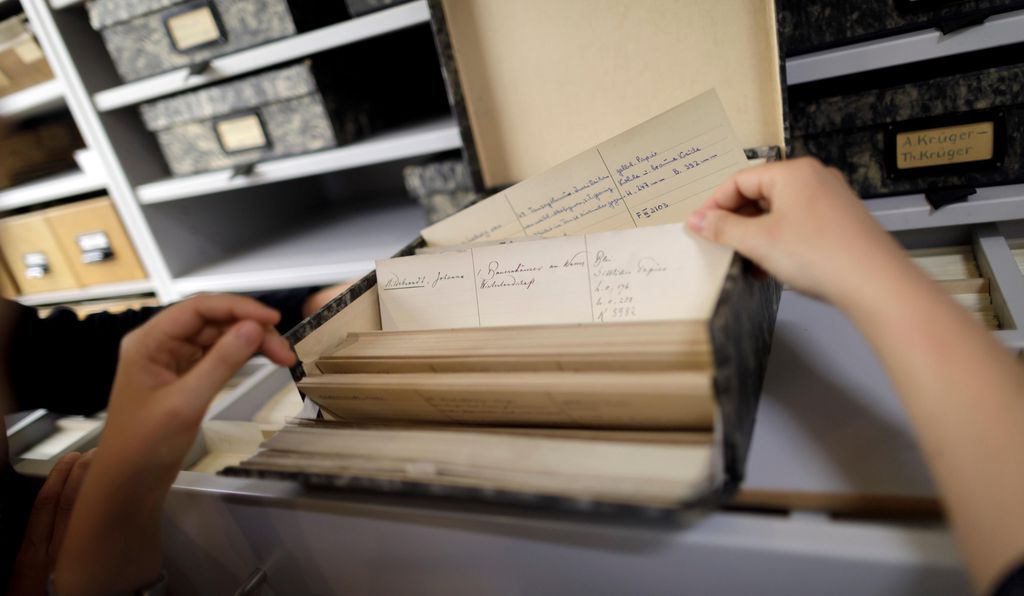

Researching the provenance of this or any other painting would be impossible without collaboration between specialists in the U.S. and Germany. That might mean sharing searchable databases or updates to laws covering the import and export of cultural property. Other times, experts on both sides of the Atlantic are literally opening their doors and archives to visiting researchers.

In Germany, academic and popular interest in World War II provenance research has exploded in the last ten years, says Petra Winter, head of provenance research and director of the Central Archives of the National Museums in Berlin. Yet in contrast to Daly’s full-time role at the VMFA, German museums can’t always find the specialists they need to do that work for the long-term.

“We don’t have enough permanent staff or provenance researchers at museums, so we hire part-time staff” to work on short-term projects, Winter says. “We have art historians who are a bit nomadic, going from one museum to another. For the museums, it’s not so good for them to have researchers move on and take their knowledge with them.”

Even for the most deeply staffed American museums, it will become increasingly challenging to hang on to institutional knowledge: Of the directors at 150 art museums in the U.S., more than one-third are over the age of 60 and approaching retirement. To help museums keep their Nazi-era provenance research consistent across staffing and administrative changes, PREP focuses on mentoring the next generation of museum professionals. PREP is exploring new software and improved technologies—currently, linked open-data is the leading candidate—to facilitate the sharing of provenance resources and results among researchers, institutions and the public. The group also plans to publish an online guide to German and American World War II-era provenance resources to improve the speed and accuracy of the research.

These plans will enhance museum stewardship and help with educating the public, says Jane Milosch, director of the Smithsonian Provenance Research Initiative. “Objects in public collections are digitized and available to researchers. On the other hand, objects which were potentially looted and currently in private collections are not bound by requirements regarding the transparency that professional museum organizations have developed. These works often disappear from public view and are not accessible to researchers.”

“Bringing to light the often-fascinating stories that provenance research reveals can enhance the exhibition of these artworks,” says Andrea Hull, program associate for the Smithsonian Provenance Research Initiative. Reviewing museum catalogs and other documents online, versus traveling to an archive to see the art and paperwork in person, allows researchers in Germany and the U.S. to make connections more broadly, quickly and affordably.

Online public archives also can let a provenance researcher know when they need to pass the baton and step away from the documents, digital and otherwise.

“There’s so many points of information that can take you on a wild goose chase or down a rabbit hole,” Daly says. “Like the attribution of a painting or object over time: The title changes multiple times. The artwork physically changes, like it’s painted over or cut down.

“You have to know when to pull back, and it’s so key to record that information and share it so someone can come along and pick up on that point where I was. [Unraveling] those kinds of things can take a while.”

In 2018 and 2019 two more PREP cohorts will convene for two semi-annual gatherings in the U.S. and Germany. Partner organizations hosting the exchanges include the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, the Dresden State Museums and the Central Institute for Art History in Munich.