When Aileen Wuornos was convicted in 1992 for shooting and murdering several men, the press dubbed her “America’s first female serial killer.” In the popular imagination, the term had long been associated with men like Jack the Ripper, Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer. Some were even more skeptical about the murderous capabilities of the “fairer sex;” in 1998, former FBI profiler Roy Hazelwood reportedly went as far as to say: “There are no female serial killers.”

Related Content

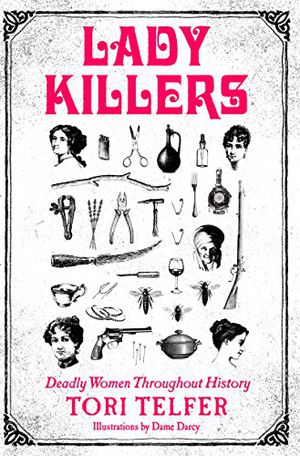

But as Tori Telfer points out in her new book, Lady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout History, this is far from accurate. She tells the morbid stories of 14 women who used poison, torture, and “hustle” to do their dirty deeds. “These lady killers were clever, bad tempered, conniving, seductive, reckless, self-serving, delusional, and willing to do whatever it took to claw their way into what they saw as a better life,” she writes.

Lady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout History

Inspired by author Tori Telfer’s Jezebel column “Lady Killers,” this thrilling and entertaining compendium investigates female serial killers and their crimes through the ages.

Particular themes repeat themselves over and over again in the book—murdering for love, money, or pure spite. And as the stories of these women have become mythologized, Telfer says, legends have come to portray them as irrational or subhuman to help explain away their crimes.

Take, for example, Darya Nikolayevna Saltykova, an 18th-century noblewoman. Obsessed with cleanliness, she would often beat her serfs mercilessly until they died. By the time the wealthy aristocrat was brought to justice, she allegedly had tortured and killed 138 people. “I am my own mistress,” she once said while watching one servant beat another to death for her. “I am not afraid of anyone.”

When other Russians found out about Darya, they leapt to write her off as “insane,” as humans tend to do when they hear about serial killers, Tefler says. In all the cases she looked at, she says, media would call these women “beasts” or “witches,” refusing to look at them as human. “There’s something in us as humans that just does that,” she says. “We do have kneejerk reactions to horror. And we do want to distance ourselves from it immediately.”

Stories like Darya’s had “poetic resonance” for Telfer—after all, who could make up a story about a Russian Orthodox woman acting like a god? She was similarly drawn to the tale of Kate Bender, the daughter of a family that owned an inn in 1870s Kansas. The 20-something hostess charmed male travelers with her beauty, convincing them to stay for dinner, then the night. And when travelers started disappearing, no one paid much attention; lots of people vanished without a trace on the wild frontier.

But in this instance, Kate was the linchpin of a murderous plot to rob wealthy travelers of their wares. She would coax an unsuspecting guest into a chair near a canvas curtain, and then her father or her brother John Jr. would hit them over the head with a hammer from behind the drapes. Kate would slit their throat, and her mother would keep lookout. They’d keep their victims in a cellar beneath their house and then bury them in the nearby orchard in the middle of the night.

“The Benders are this metaphor for the American West, the dark side of the frontier and westward expansion,” says Telfer. “I would almost think it was just a myth if we didn’t have photos of their townhouse and the open graves. “

In picking her favorite stories, though, Telfer had to sift through a lot of other gruesome tales. She refused to touch the world of “baby farmers,” who would adopt poor people’s children in exchange for money and then neglected or killed them. Murderers who operated since the 1950s weren’t eligible for consideration, either, so she could limit her timeframe. She also passed over the countless stories of mothers who killed their children with arsenic—a common method of infanticide—unless Telfer found something that “pinged” something inside of her.

Writing about serial killers’ mental state proved particularly tricky. Telfer uses “madness” when describing the different killers’ motivations, because she didn’t want to “armchair diagnose from centuries later,” she says. She also didn’t want to stigmatize people who have mental health disorders by linking them to serial killers. “Schizophrenia didn’t make her serial kill, because that’s not how it works,” Telfer says.

Many of these women murdered in an attempt to grasp control over their own lives, Telfer writes. They killed their families for early inheritances, while others killed out of desperation in abusive relationships or revenge for people who had hurt them.

Telfer feels some empathy for these women, even though they committed horrible crimes. Life treated them unfairly, like in the case of a group of older women from Nagyrév, Hungary. All of the women were peasants over the age of 55, living in a small town besieged by post-World War I societal strife and poverty. The harshness of everyday life meant that mothers often poisoned their newborns, who were seen as just another mouth to feed, and no one reported the crimes. And when wives started killing their husbands and other relatives, people turned a blind eye.

But that doesn’t excuse their actions, Telfer says. “A lot of people in interviews sort of seem to want me to say the perfect feminist soundbite about these women,” she says. “And I’m like, well they’re terrible! I can’t ultimately be like, ‘and go, girl, go!’”

But it made her think a lot about the classic “nature versus nurture” debate and how serial killers might fit in with that.

“Ultimately, I enjoy thinking about human nature, and serial killers are like human nature in the extreme,” Telfer says. “I think you can learn a lot from studying them and thinking about what does it mean that, as humans, some of us are serial killers?”