Markus Lüpertz has been showing his splashy German neo-expressionist paintings in Europe galleries and museums for more than 50 years. But only now is he strolling through his first major U.S. museum survey, shared by two different Washington, D.C. institutions.

“I never see these paintings because they are in collections or in warehouses,” he says approvingly through an interpreter.

One, at the Phillips Collection, Markus Lüpertz is a survey of his entire career, with works from 1964 to 2014. The other, at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Markus Lüpertz: Threads of History, concentrates on the period from 1962 to 1975, which curator Evelyn Hankins calls his “early mature work.”

But the artist himself, at 76, had a hand in its presentation, at least at the Phillips Collection.

Phillips collection director Dorothy Kosinski, who curated its retrospective, said her approach was originally the traditional overview—with a statement and artists’ picture to begin, followed by the work, carefully presented chronologically.

“What happened was, Markus Lüpertz walked in and he said, ‘I’m going to look around.’” As a result, Kosinski says, “Every painting in this exhibit of 50-some works moved—and many of them more than once or twice.”

The upending of the curatorial process wasn’t rattling, Kosinki assured me. On the contrary, she told me, “I felt set free.”

“You saw the artist himself choreograph, orchestrate the entire exhibit, and as he says, optically, intuitively, having to do with different sizes, colors and conversations between pictures,” Kosinski says. In that, it was in the manner of founder Duncan Phillips, who opened the Dupont Circle gallery as America’s first museum of modern art in 1921, and would hang works regardless of genre or date.

As it was with Phillips, the Lüpertz’ process was “not art historical, it’s intuitive. It’s passionate,” Kosinski says. Additionally, the museum founder was all about painting, and so are these two exhibits—though Lüpertz is also an accomplished sculptor as well as poet, writer, set designer, jazz pianist and a professor of art.

“This is an artist with a huge, huge appetite for expression,” Kosinski says.

For the two institutions, it’s a landmark. Although they had concurrent exhibitions of artist Bettina Pousttchi last year, it’s the first formal collaboration and includes a joint catalog with contributions by both curators. “Hopefully it sets a precedent for future collaborations,” the Hirshhorn’s Hankins says.

Markus Lüpertz

Having worked as an artist for more than sixty years, Markus Lüpertz has achieved the highest recognition internationally as a result of the suggestive power and archaic monumentality of his painting style.

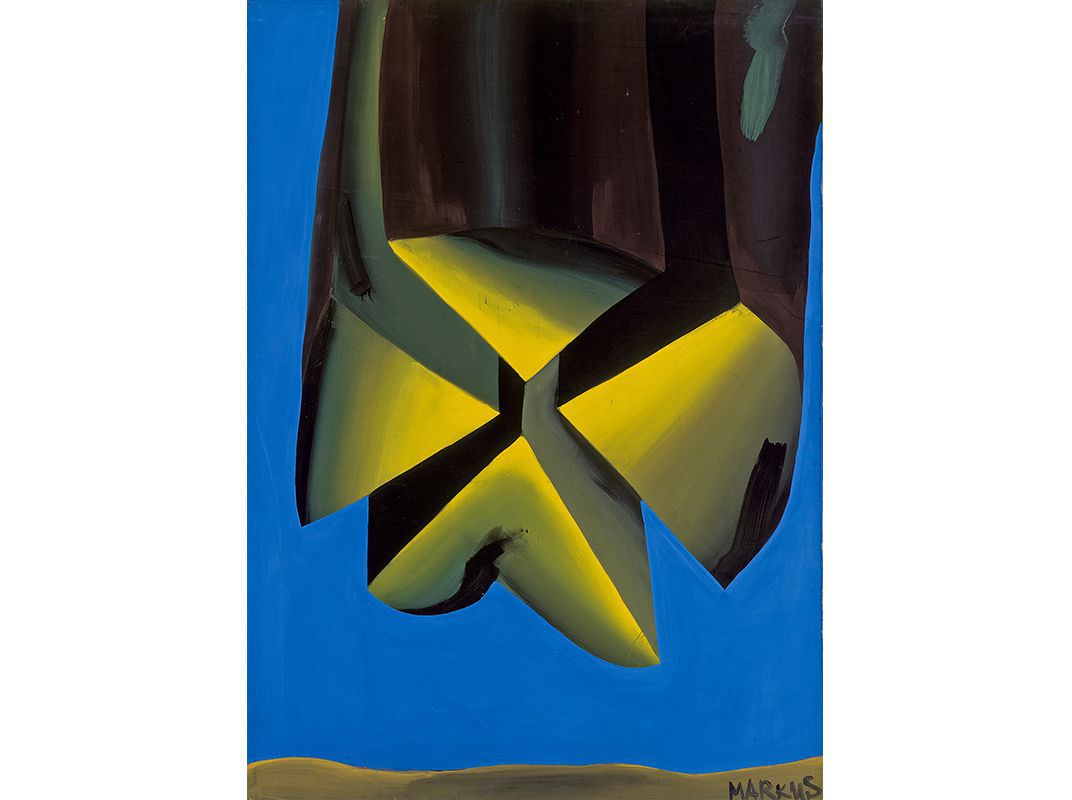

Lüpertz has been groundbreaking in his work as well, using motifs that were still touchy in German history, such as the distinctive Stahlhelm helmet in his canvases. In others, he took on images not usually monumentalized by large canvases, from logs to spoons to camping tents.

Early in his career, Lüpertz painted tryptic-like “dithryambs” with similar motifs presented in threes. Some of those are on display at the Hirshhorn.

When he broke up the Phillips presentation, he split the dithyrambs as well. “That’s the reason why I love to do exhibits like this,” says Lüpertz, looking natty in his three piece suit, hat and gold-tipped cane. “Because I’m not interested anymore in the serial aspect, but in the individual painting.”

“You are forced to look at the individual painting—painting by painting,” Lüpertz says. “That’s my idea.”

Born in what is now the Czech Republic in 1941, Lüpertz emigrated to Germany in 1948, and worked as a coal miner and construction worker before turning full time to painting, moving in 1962 to West Berlin. “It’s important to remember Germany came a bit late to avant grade painting in the 1940s and 1950s because of World War II and Hitler’s approach to culture and the avant grade,” Hankins says. “German artists were not really exposed to key historical moments in European painting in the 1920s and 1930s and even into the 1940s.”

It wasn’t until the 1950s that abstract expressionism, much of it from America, began traveling through Europe, she said. Only then did artists of Markus’ generation have the opportunity to see works by artists such as Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston and Roy Lichtenstein.

“We were so enchanted. We were obsessed by it,” Lüpertz says. “It was such a fantastic style of painting, such a fantastic liberation of painting, and we all took advantage of that.”

And another inspiration from America were the comics, he says. “The comics, for me, spoke a new language,” he says. “It was new for me, different—American. It was my curiosity in those days I had for the United States.”

The result were striking works like Donald Ducks Hochzeit (Donald Duck’s Wedding) and Donald Ducks Heimkehr (Donald Duck’s Homecoming) that combine a hint of the Disney character with the slashing paint stokes of de Kooning.

Lüpertz moved to variations on the 20th Century Fox logo, a spoon, or a series of works on tents in vibrant colors.

The biggest work in the Hirshhorn show, the 1968 Westwall (Siegfried Line), takes on the supposedly impenetrable series of bunkers along Germany’s western border, and considers it more like an earthwork than a wartime embankment.

Hankins says the scale itself was a statement in Westwall, which has never been previously shown in the U.S. “The incredible ambition to paint a painting that was 40-feet long was a very big thing back in the 1960s. It wasn’t something that happened all the time.”

She pointed out a more modest work of the same time Wasche of der Leine (Washing on the Line) that used some of the same motifs, such as tree trunks and fabric. “But what’s critical about it is that we figured out that actually it was a song that was sung by the British soldiers called ‘We’re Going to Hang the Germans on the Washing Line,’” Hankins says. “This is no longer a painting that is purely a motif of interest to the artist, but it also takes on a political aspect, which I think is a critical turning point in Markus’ career in the 1960s.”

That was news to Lüpertz.

“I don’t even remember that,” the artist says of the political interpretation, indicating he might not have meant to reference that song at all. “You can have many interpretations in a painting.”

That comes also with the touchier depiction of German helmets.

“A helmet is something which fascinated me as a person very much,” Lüpertz says. “But there is a history attached to a helmet. I am not responsible for the history behind the helmet, because the helmet tells its own story. I was only painting it.

“The same thing with the skull,” he says, “or with a hill or with a nude. It’s the subject which tells the story. The painter is interested in how he makes the painting.”

Lüpertz’ newest works, as seen at the Phillips, combine classical figures interacting with others, as in the 2013 Arkadien – Der Hohe Berg (Arcadia – the High Mountain)—works that also featured painted frames.

That’s because he doesn’t want his work to fit so decoratively on a gallery wall, he says. “The frame detaches the painting from the wall. It actually creates its own space. I would make another five or six frames on top of that. I’m always fighting with my galleries because that person thinks one frame is sufficient. Because I do not want a painting to be decorative. A painting makes its own claim. I think the painting changes a room.”

And so, the two shows of Lüpertz works may also change Washington, and perhaps also the U.S.

“What else could I hope for?” the artist says when asked if he hopes he’ll find a bigger U.S. audience. For a man who signs his paintings with his first name so it can be “in the great European tradition” of Rembrandt, Michelangelo or Vincent, Lüpertz says a little devilishly, “I hope that this is going to help with my own personal glory. And I still have to conquer the United States. So I am a little bit like Columbus.”

Seeing the two exhibitions, “For me, it’s a dream. It’s a vision,” the artist says, “When I think about the fact that some of these paintings are more than 40 years old, 50 years old, I’m very surprised. Because I could have been painting these paintings yesterday. For me, there was no time elapsed between these paintings.”

Accordingly, “I hope to be able to get a bit of eternal life,” he adds. “Because there is no death in painting.”

Markus Lüpertz continues at the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. through September 3. Markus Lüpertz: Threads of History continues through September 10 at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, also in Washington.