It’s a chilly, rainy November afternoon, and abstract artist Mark Bradford is talking about levitating. Two years ago, working on a commission for the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, he had a vision of himself floating in the center of the building’s courtyard space. He recalls thinking, “I’m standing in the middle of a question,” facing the work as “a problem I needed to solve.”

The Los Angeles-based painter was at the Hirshhorn for the opening of his new solo exhibition. The installation Pickett’s Charge spans almost 400 feet and consists of eight canvases measuring 12 feet tall and more than 45 feet long. It riffs on the even-larger 1883 cyclorama by artist Paul Philippoteaux’s paintings of a pivotal Civil War assault. It was on July 3, 1863, the third and final day of the Battle of Gettysburg, that Gen. George Pickett and his Confederate troops failed to break through the Union’s line. That historic defeat turned the tide for Union forces.

To portray the event accurately, Philippoteaux—a self-styled cyclorama specialist from Paris—interviewed survivors and researched military strategy. As he worked on the paintings and the accompanying dioramas, “he didn’t take a side,” says Evelyn Hankins, the Hirshhorn’s senior curator. “He depicted the valor of the soldiers—the honor of fighting and the passion—rather than taking a side.”

A 3D effect of playing with depth and perspective, combined with jaw-dropping depictions of literary, religious and military scenes, made cycloramas very popular in late-19th century Europe and America. The meticulously restored Gettysburg Cyclorama remains one of few such works on view in the U.S.

For Bradford, the cyclorama and other early American paintings raise questions about the politics of military memorials. “How many times do we walk by old, dusty monuments,” he says, and think deeply about what they signify? He’s speaking not only of Confederate statues and the debates over whether they should stay or go, but also of the Vietnam War-era helicopters that he noticed on the grounds of the National Archives adjacent to the Hirshhorn. The helicopters were temporarily installed for the opening of show about Vietnam. These displays defy objectivity—Americans can’t agree on which events to honor, forget, ignore or criticize, so he asks: “How do we write history? Who has the power to write. . . and contest history?”

He indirectly suggests that we all have that right and responsibility, arguing that “to question power is the cornerstone of democracy.” The key, he says, lies in open-ended conversations fueled by curiosity. Questions invite dialog, he says. “Answers just close people down.”

To keep the dialog open, sometimes nudging it into uncomfortable or unexpected territory, Bradford uses different media to reflect America’s history back to itself. His first solo museum exhibition in L.A. included Spiderman, a video piece that parodies sexist and homophobic stand-up comedy routines from the 1980s, and Finding Barry, a carved map highlighting HIV-infection rates in the U.S.

After Hurricane Katrina, he built Mithra, an ark standing 70 feet tall featuring FEMA signs that survivors used to try to locate lost pets after the storm. Currently on view at the L.A. County Museum of Art is 150 Portrait Tone, a mural-size painting responding to the police shooting in St. Paul, Minnesota, of Philando Castile.

The recipient of a 2009 MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, Bradford grew up in a boardinghouse in 1960s South Central Los Angeles. The elder of two kids, he never knew his dad; his mom worked as a hairstylist. In the early 1970s she decided to move her family to a safer part of L.A.—he calls it “the Santa Monica of. . . Birkenstocks and socialist natural food stores.” His mother eventually opened her own salon in Leimert Park, close to their earlier neighborhood. After high school, he got his hairstylist’s license and went to work with his mom.

As a gay, black man in the 1980s, he saw people he knew from the L.A. club scene and their counterparts elsewhere dying from AIDS-related illnesses. Hoping to evade their fate, he intermittently escaped to Europe for most of his 20s. He would stockpile his hairstyling income and travel until the money ran out, then work some more, save and roam all over again.

By his early 30s he had resettled in L.A. and enrolled in art school. He experimented with different media and devoured the writings of philosophers and art theorists, earning bachelor’s and master’s of fine arts degrees from the California Institute of the Arts. He continued working at his mother’s salon, while also making art, figuring out how to use Abstractionism to investigate race, gender and socioeconomics. A 2001 group show at the Studio Museum in Harlem put him on the wish lists of collectors all over the world.

Bradford’s paintings typically sell for a million dollars. To create these works, he scavenges material from the streets of L.A., a practice that dates back to his days after art school, when he couldn’t afford acrylic and other pricey supplies. He prefers to use found objects, “pulling things that don’t belong in the art world and willing them into it.”

He also might add house paint, or endpapers used for chemical hair treatments, or the colorful advertisements for payday lenders and other businesses targeting lower-income residents. He layers these elements into large collages, then scrapes, singes and discolors the paintings using power tools, bleach and other methods.

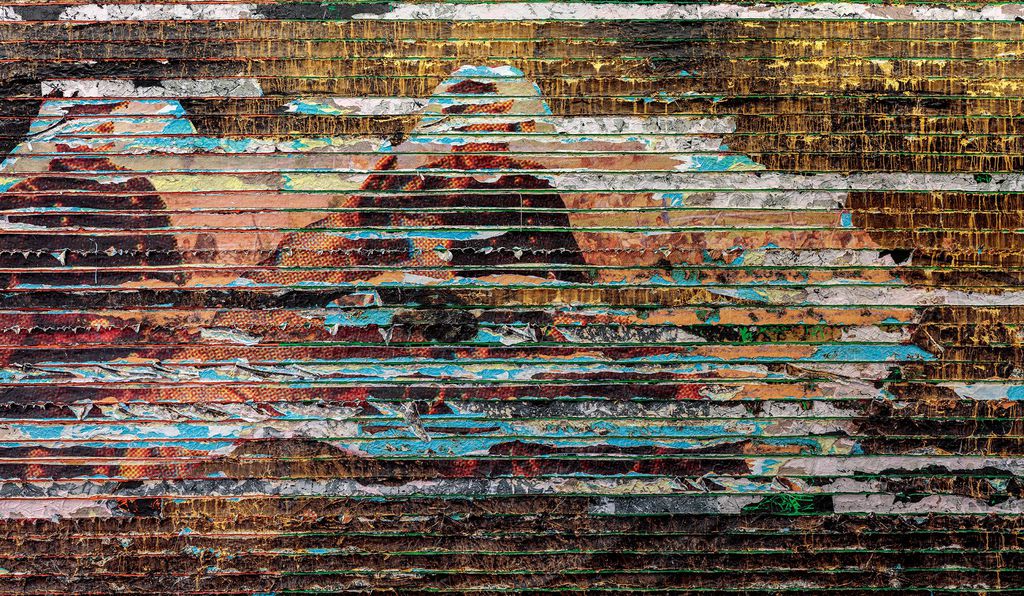

For Pickett’s Charge, he had digital images of the Gettysburg Cyclorama printed on blue-back billboard material, which prevents images and lettering on the underlying layers from visually bleeding through. To create a kind of scaffolding, he fastened thin ropes into dozens of horizontal rows, four inches apart, on massive canvases.

“I was so frightened when I realized how big 400 linear feet is,” he says, that he needed the ropes to create a “grounding mechanism [for me] to not panic.” He likens them to an archeologist’s controlled explosion that allows methodical digging to the history underneath. The ropes became the underlying architecture. “I don’t sketch much,” he explains. “I work out everything by laboring.”

He applied sheets of paper in colors like those from Philippoteaux’s painting and laid on the Gettysburg imagery last. Then he gouged the billboard material, tugging at his guiding ropes and the paper layers. The “echoes” of the pulled-off ropes created concentric circles running across the canvases. Like he has in earlier works, he scratched and tore these paintings by trial and error until he felt they were complete.

The location of the museum along the National Mall inspired the paintings as much as the circular Hirshhorn gallery in which they hang. “I was always obsessed with what happened on the Mall,” he says. “It’s a site for rituals of democracy and dissent,” like the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963 and the Women’s March in January 2017. Bradford’s historical research for Pickett’s Charge focused on the overlooked contributions of women during the Civil Rights movement.

In the Hirshhorn gallery, Bradford is standing in front of Dead Horse, the last of the Pickett’s Charge paintings he created, and describing how his process has changed over the years. “There’s a three-dimensional quality that I never let happen as much [before],” he says. “The physicality of the surface is jumping off a bit more. The fissures I’m allowing to be there—it’s not as ‘pretty.’” He flutters his fingers over the canvas and says, off-handedly, “I can see the echoes of Venice here.”

“Venice” is the Venice Biennale, the prestigious, juried art extravaganza held every two years in Italy. Through a collaboration between the Baltimore Museum of Art and Brandeis University’s Rose Art Museum, Bradford created Tomorrow Is Another Day, an immersive installation of sculptures and paintings, for the Biennale’s U.S. pavilion. The exhibit takes its name from Vivien Leigh’s last line in the 1939 film Gone with the Wind and explores blackness in America, from slavery to recent police shootings and acquittals.

The sociopolitical impact of his work, Bradford says, “is not always coming from the paintings.” He hasn’t really separated his art from his activism, either. “I never saw the difference,” he explains. “It’s all connected to me.” He used the Venice show to announce a six-year partnership with Rio Terà dei Pensieri, a local cooperative that provides prison inmates with job training and helps them adjust to life after they’re released.

Economic sustainability has been a longtime passion of his, since the days of “me and my mom working in the beauty salon,” he says. “Keeping the mom-and-pop businesses going. I’m interested in access and filling a need” in the community.”

Prior to the Venice collaboration, he’s had more formal practice melding art and advocacy: Three years ago, Bradford, Allan DiCastro (his partner of 20 years), and philanthropist Eileen Harris Norton co-founded Art + Practice, an arts and education foundation that offers support services to foster youth and cultural events. The organization’s headquarters includes the building that once housed his mom’s salon in Leimert Park, one neighborhood away from the old boardinghouse of his childhood.

“Mark Bradford: Pickett’s Charge” is on view at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. through November 12, 1018.