For the past 96 years, the annual Santa Fe Indian Market has been the largest cultural event in the Southwest, bringing together upwards of 1,100 Indigenous artists from the U.S. and Canada, and 150,000 visitors from around the world, more than doubling the New Mexican town’s typical population. Indian Market takes place the third weekend in August, and it has long been considered the most prestigious arts show in the Native community.

A component worth mentioning to visitors is that they’re able to browse and collect from a huge selection of work with the knowledge that each piece is an authentic creation. Given the prevalence of the foreign-made fakes market, a competitive component that has taken work away from Native American communities for centuries, shopping, collecting and trading at the Santa Fe Indian Market is a safe and ethical way to ensure that investments are being made into the Native community where they belong.

For artists, the road to Indian Market is not necessarily an easy one. Artists from 220 U.S. federally recognized tribes and First Nations’ tribes work incredibly hard to have their work included during the annual event, and not every applicant gets the opportunity to be part of the festival. Everyone takes their own path to Indian Market, and just like the art, the creators have their own stories to tell.

Monty Claw is a Navajo beadworker, painter and jewelry-maker (among other artistic talents), hailing from Gallup, New Mexico. He first applied (and got in) to the Santa Fe Indian Market in 2005, after which his art enabled him to leave an unsatisfying career of construction work behind, instead thriving with the diverse artistic talents he brought with him from childhood.

“The reason I do Indian Market is because it’s basically the World Series of Indian markets. It’s the place to be.” Claw explained that this is the best place to see the greatest collection of living artists, so not everyone who applies gets in. This is why he continually strives to “step up his game,” a practice which led him to jewelry-making, in order to “bring out how a creative mind works within a cultural background.”

Claw sees Indian Market not just as a place to tell his own story, but to encourage the next generation of artists as well. “Today’s younger artists have that feeling of ‘where do I belong, how do I express myself?’” As generations with more blended backgrounds are born, there can be shame among those who don’t speak Navajo (like Claw) or who aren’t as in touch with their cultural roots. “We shouldn’t push them away. That’s why I like Indian Market, because you have all this cultural diversity in one area and you hear their stories. They encourage you, and it makes you feel really good.”

Liz Wallace is a silverworker originally from Northern California, with Navajo, Washo and Maidu heritage. For Wallace, being an artist is a way to show what it means to be Native American while staying true to her passion. “What’s unique about Native art is that we bring everything — thousands of years of history — the sociocultural context. These crafts have been passed down through generations. And that’s how so many of us are able to make a living and stay in our communities.” This is why, she says, the fakes industry is so harmful: it literally displaces Indigenous people from their homes.

It’s worth noting that Wallace, like artists from every background, creates work based on her individual interests and style, which at times incorporates contemporary and traditional themes. “Even though a lot of my work is Japanese-inspired, by making jewelry I feel like I’m part of the narrative of Navajo silver and adornment.”

Kelly Church comes from an unbroken line of Anishnabe black ash basket makers in Michigan, a practice that for Church began as utilitarian, but quickly became a way to reflect her own story. “The story of resilience, the story of continuation, the story of tradition. Even though we keep changing… the ways that we do things…these baskets mean that we are still here today.” Indian Market has been one of the venues through which she’s been able to share this story, which carries a tremendous amount of meaning.

Since the late 1990s, over 500 million harvestable black ash trees have been lost to the emerald ash bore, a hardy, relentless bug that was introduced to the forests of Michigan by way of wooden pallets from China. The bug devastated the black ash supply for Church and her family, but it also got people to pay attention to their history. “Sometimes it takes something like the bug to draw them in to wonder, ‘what’s the story’ and how they relate to you.”

While waiting for the black ash population to recover, which could take upwards of 50 years, Church has had to raise her prices and reduce her output in order to preserve baskets for future generations of her family. “I used to be able to go 15 minutes down the road [for materials], and now I have to drive 8-10 hours, plus rent a truck. It’s become expensive for me to make the baskets.” The status of this long-held tradition and the availability of this beautiful art has changed in the blink of an eye, making it more important than ever to see the baskets in person and understand what they represent.

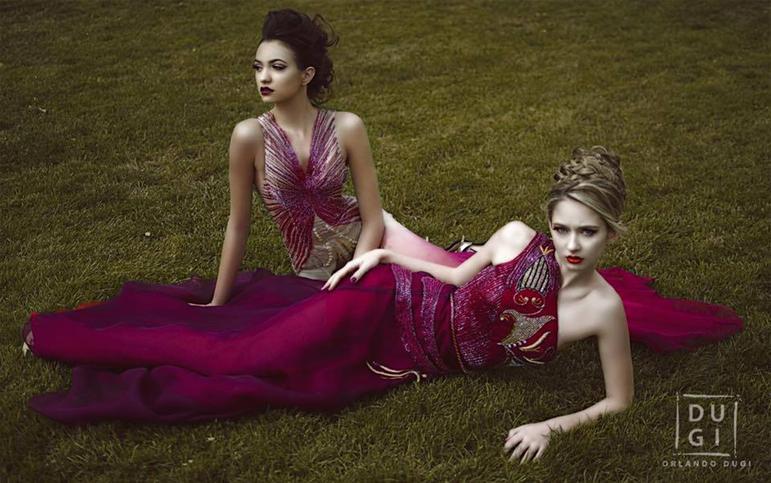

Orlando Dugi is a Navajo fashion designer whose couture gowns and innovative stylings have been featured on the runways of New York Fashion Week. Dugi’s contemporary work challenges the preconceived notions of what qualifies as “Native American Art,” and this has been supported by the Market. “They’re trying to promote contemporary Native American artists, but they still cherish the old artists. They’re trying hard to include everybody in this market – that’s what I like about it, and that’s I think what makes it so successful.”

All of these artists and more will be showcasing their work at the Indian Market this weekend, August 19-20, 2017. Whether you’re looking to build a collection or see the breadth of work by talented, passionate artists in the historic setting of Santa Fe, Indian Market has something for everyone, thanks to the many paths that bring so many different backgrounds together.