Norman Rockwell, the master of Americana, captured the essence of daily life in hundreds of 20th-century magazine covers, and 75 years ago this month, he accomplished a greater feat, translating the nation’s ideals into indelible images known as the Four Freedoms.

By illuminating rights that every American—and every person—should enjoy, Rockwell’s Four Freedoms validated the U.S. decision to enter World War II and overcome powerful enemies whose actions devalued human life. His enduring messages have lingered in the national consciousness, remaining as significant today as they were when the Saturday Evening Post published them in four consecutive weeks during the winter of 1943.

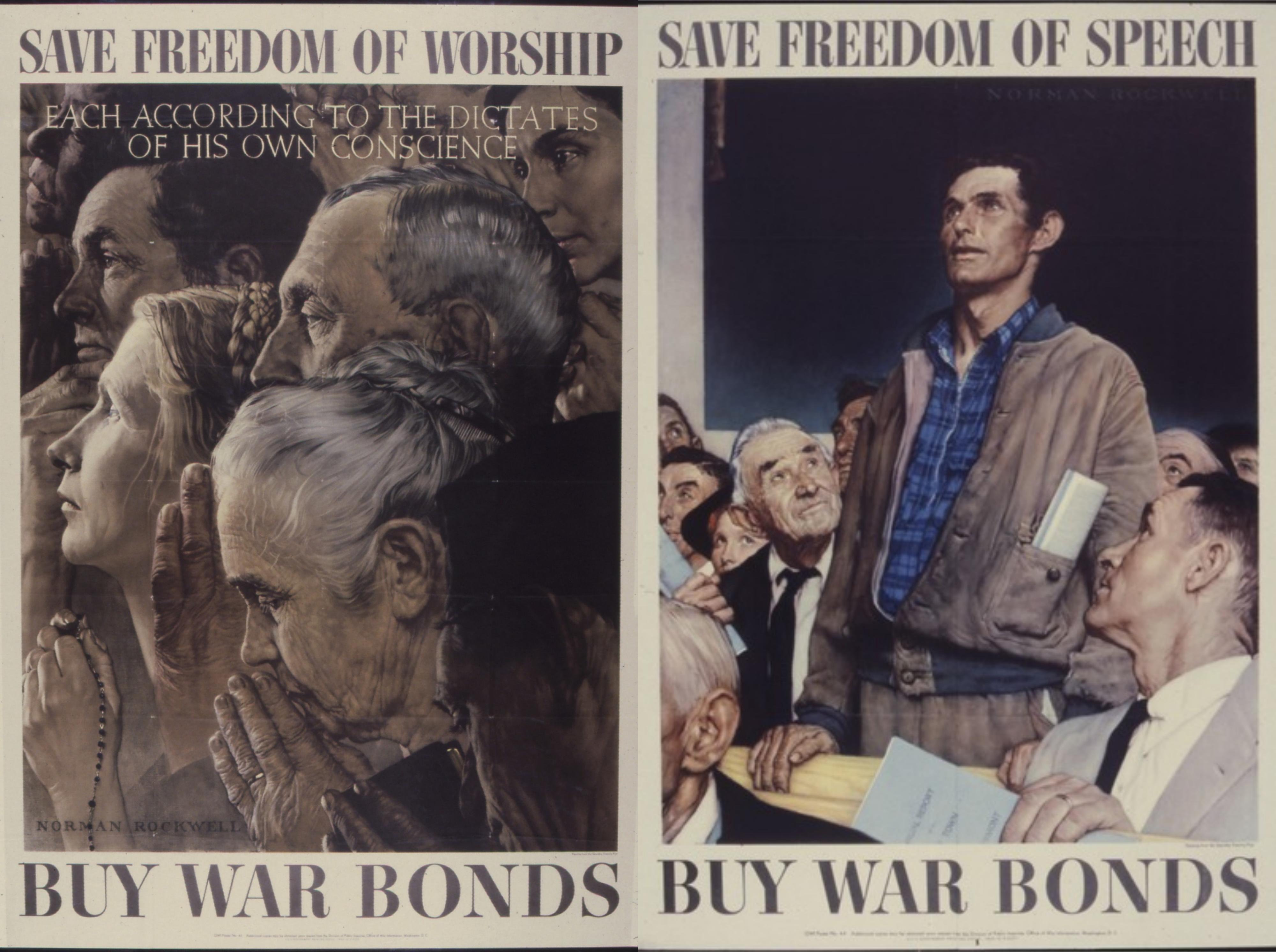

Rockwell’s images had a clear meaning, says the Smithsonian’s Larry Bird: “Why we fight, what we’re about, what we’re fighting for, what we’re fighting to save.” Bird is co-curator of the National Museum of American History’s exhibition “American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith,” which features a large set of the original Four Freedoms war bond posters from 1943.

Immediately after publishing Rockwell’s four paintings—Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion, Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear—the magazine received 25,000 requests to purchase copies. Color reproductions of all four sold for 25 cents apiece. The paintings became the basis for 4 million war posters sold as part of the War Bonds effort, raising $132,992,539. “They were received by the public with more enthusiasm, perhaps, than any other paintings in the history of American art,” The New Yorker reported in 1945.

Within weeks of publication, Rockwell’s paintings began a national journey. Across 16 separate cities, a total of 1.2 million people lined up to see the paintings, which were put on display in department stores, not museums. Those who bought war bonds received color reproductions in return. After completing that tour, the paintings rode the rails to a wider assortment of towns and cities, where Americans could admire Rockwell’s works in a custom-made train car.

Although the paintings became famous as an endorsement of the struggle to defend American ideals in World War II, the Four Freedoms first entered the American lexicon in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s January 1941 State of the Union address, almost a year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor swept the United States onto the field of battle. At the beginning of 1941, when isolationist sentiments still held sway over many Americans, Roosevelt’s goal was a simple one: to convince voters that standing alone ultimately could sacrifice freedoms at home and abroad.

“By an impressive expression of the public will and without regard to partisanship, we are committed to the proposition that principles of morality and considerations for our own security will never permit us to acquiesce in a peace dictated by aggressors and sponsored by appeasers,” he told Americans. “We know that enduring peace cannot be bought at the cost of other people’s freedom.”

FDR then described the four freedoms every human being should enjoy—an addition to the speech that the president himself made in its fourth draft. He wanted to make Americans understand why the United States should provide material support for the western Allies as they battled Germany’s Nazi regime and the Japanese empire, both of which were stripping away individual rights. At the time, Roosevelt was convinced the United States was not ready to enter the war, but he believed armaments production for the Allies represented one way to protect cherished freedoms without risking American lives. While his speech planted a seed of inspiration in Rockwell’s brain, staunch isolationists rejected FDR’s message, claiming that it promoted war.

The United States and Great Britain wrapped Roosevelt’s ideas into the Atlantic Charter issued in August 1941. Both the State of the Union and the Atlantic Charter represented these freedoms as international ideals—rights that should belong to anyone anywhere. And through international initiatives such as disarmament and economic stability agreements, any nation should be able to exist without fear and with the opportunity to offer broad rights to its citizens.

For Americans, the First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees freedom of speech and freedom of religion. “Freedom from want” and “freedom from fear” are nowhere in the nation’s founding documents, but they reflect the hopes of a nation emerging from the Great Depression and preparing to enter the biggest global conflict ever. “They are aspirational goals that we, or at least those who believed in the sort of New Deal politics, saw as the role of government,” says Harry R. Rubenstein, who also curated the museum’s exhibition American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith and, like Bird, is a contributor to a book bearing the same title.

Seventeen months after FDR’s address, Rockwell traveled to Washington to promote his idea of illustrating the Four Freedoms to bolster the war effort. His autobiography states that not one official initially welcomed his proposal. The hard truth was that there were people inside and outside of government who questioned the artistic value of Rockwell’s storytelling works, which were often equated with advertising illustrations. Ultimately, though—and the historical record is unclear on the details here—Rockwell was able to persuade the powers that were, reaching an agreement to produce the paintings for the government and the Saturday Evening Post magazine.

After promising to create the images, Rockwell faced the difficult task of transforming governmental phraseology into evocative tableaux on canvas. He had expected to finish all four scenes in two months, but the work dragged on through seven months of false starts and revisions.

Nonetheless, Rockwell was fully committed to the Four Freedoms. “I just cannot express to you how much this series means to me. Aside from their wonderful patriotic motive,” he told his impatient editors, “there are no subjects which could rival them in opportunity for human interest.”

With the February 20, 1943 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, the paintings began appearing weekly, each accompanied by an essay. Freedom of Speech features a blue-collar worker speaking to a room filled with more finely dressed Americans, all listening intently to the Lincolnesque figure’s words. Freedom of Religion depicts several individuals of different religious backgrounds in a moment of prayer. A man wearing a fez holds a Bible or Koran; a woman fingers a rosary. Rockwell worked for two months on this painting, which carries an inscription: “Each according to the dictates of his own conscience.” The artist said later that he could not recall the source of the words; however, almost identical language can be found in the “Thirteen Articles of Faith” written by prophet Joseph Smith in 1842 to explain the bedrock beliefs of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons).

Freedom from Want pictures a large, healthy family eagerly awaiting a Thanksgiving feast. In Freedom from Fear, a mother and a father check on their sleeping children. In the father’s hand is a newspaper reporting the bombing of London—the only international reference in all four paintings. Rockwell finished these two paintings most quickly, and later said he thought they were the weakest. However, Bird says Freedom from Fear “continues to speak to me, just in daily life. And in that sense, it’s timeless.” Whether the headline refers to German attacks on London or to frightening developments in today’s world, the painting’s message applies.

While the Four Freedoms experienced huge success within the United States, they met a less receptive audience abroad. FDR described freedoms that should belong to everyone in all nations. Rockwell’s paintings, on the other hand, showed recognizably American scenes and seemed to celebrate life in the United States. Like most of his works, they portrayed Americans as a humble, God-fearing people who enjoy a strong and prosperous family life.

Freedom from Want features a dinner table laden with food—an image that rankled non-Americans suffering from the effects of wartime shortages. The sumptuous scene is colored by a playful Rockwell smiling up at the viewer from the lower right-hand corner. (This occasional representation of himself, much like film director Alfred Hitchcock’s cameo appearances in his suspenseful films, offers an unexpected dash of humor. A single eye on Freedom of Speech’s right edge also belongs to Rockwell. He thought that inserting part or all of his face into scenes appropriately cast doubt on connections between art and truth.) Freedom from Fear, too, irritated some people in Allied war zones who were unable to protect their children from an immediate threat. Oceans away from World War II’s battlefronts, Rockwell’s protective parents enjoyed an extra layer of safety unavailable to parents in most nations at war.

Rockwell’s simple images transmit complex messages. What Bird calls “his toolkit” included Rockwell’s interpretation of “human nature, human condition, irony, juxtaposition of things”—all part of a technique now well-known to most Americans. Rubenstein believes “the genius of his work is taking a very lofty ideal and bringing it down to the most personal experience.” He also sees Rockwell’s choice of domestic scenes as one of the paintings’ strengths: “These aren’t the politicians; these aren’t heroic soldiers. These are the people who support the nation, or what the nation had been and hoped to be again.”

Roosevelt admired Rockwell’s skillful delivery of a potent message. “I think you have done a superb job in bringing home to the plain, everyday citizens the plain, everyday truths behind the Four Freedoms,” he told Rockwell. Says Bird, the artist “dramatized their meaning in a way that was not available to Roosevelt, as great as he was as a radio orator and as a communicator.” Capturing idealized visions of Americans, what Bird calls “our better angels,” empowers Rockwell’s art.

After the war, the already well-traveled paintings made another national expedition aboard the Freedom Train. More than 3.5 million Americans in 326 cities saw them on that 1947-48 trek. The offices of the Saturday Evening Post served as the paintings’ home throughout the 1950s and most of the 1960s, with Rockwell finally reclaiming them before the magazine closed its doors in 1969.

Today, the paintings reside in the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, but this year, they begin another tour, entitled “Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & The Four Freedoms.” It starts in May at the New York Historical Society, and visits Detroit, Washington, D.C., Houston and Caen in Normandy, France.