It’s a warm day in May, and a group of locals are gathered on an upper floor of a Helsinki flat that’s undergoing construction—its walls covered with sheets, with tools strewn throughout. In one room, a group of strangers is seated upon floor cushions, each of them holding a piece of cardboard with a number scribbled on it. In the next are several home chefs preparing Japanese treats like saba and maki nigiri, plating them in pairs on a stack of ceramic tiles. In just a few moments, an auction will commence.

Welcome to Restaurant Day, a worldwide food carnival that originated in Finland’s capital city and has since expanded around the globe. It’s a day on which anyone can open a pop-up restaurant, allowing their imaginations to run wild. And while it began as a one-off event, thousands of people have since joined forces, opening and experiencing food-and-drink-centric pop-ups in cities, towns and villages worldwide. The next international Restaurant Day takes place on May 20, and its fans are eagerly waiting.

Finnish native Timo Santala and his friends first came up with Restaurant Day during the spring of 2011 while tossing around ideas to create something that would bring people together. A month later, the part-time journalist, photographer and event organizer was serving up gin and tonics from a bicycle bar that he peddled along downtown streets, while all around him were temporary stands, stalls and eateries selling everything from chocolate-covered bacon slices to bowls of crayfish soup. In fact, the inaugural event was so successful that the group decided to host it again just three months later. With that, Restaurant Day became a seasonal event, taking place four times annually over the next five years.

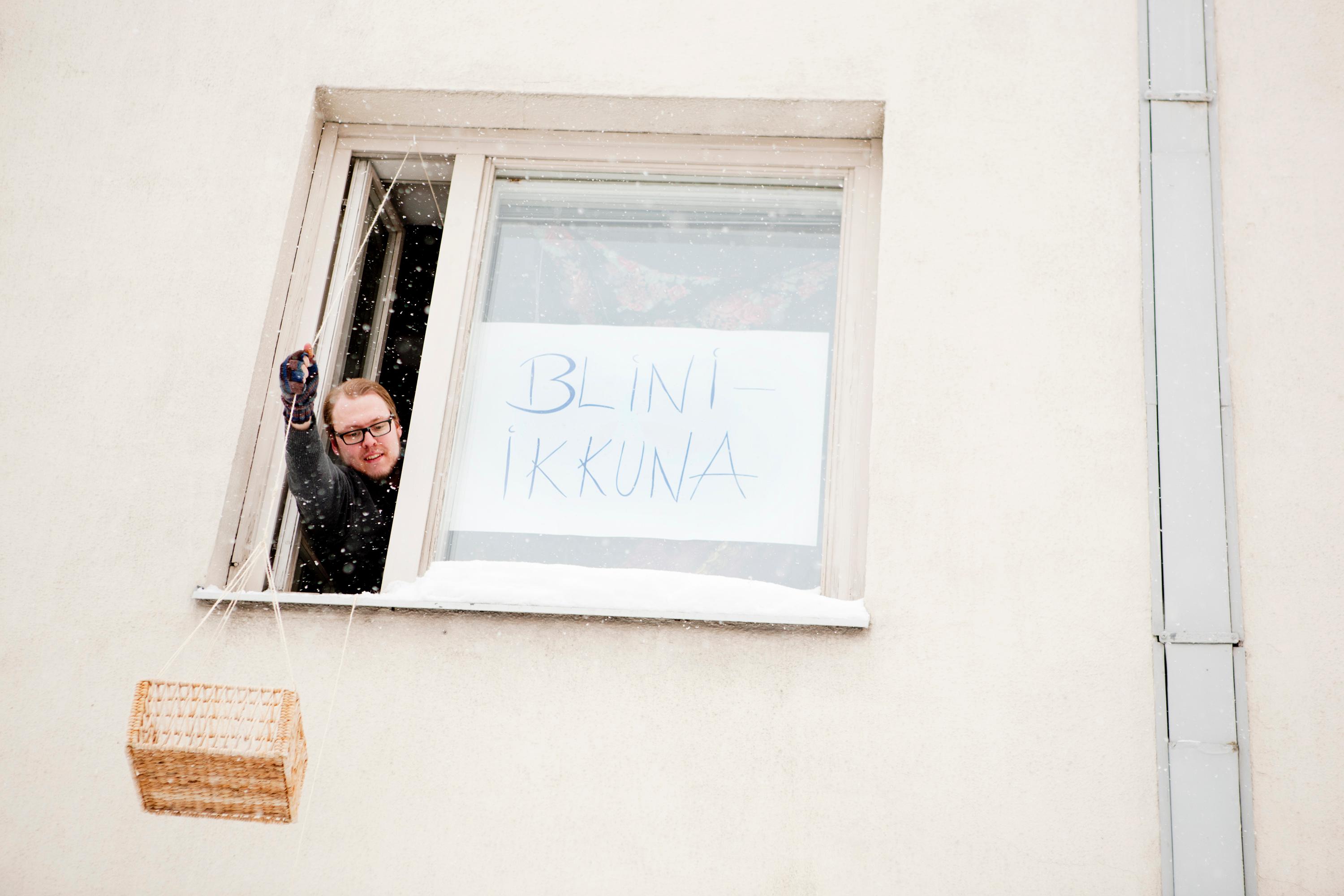

From its inception, Restaurant Day has been an outlet for originality. There have been purveyors of Viking-inspired dishes served from a tattoo shop, blinis delivered by basket from a third-floor window and a Somali family who hosted a traditional dinner within their own home. Santala even expanded on his “mobile bar” idea, this time trading in his bicycle for trench coats, which he and and a friend lined with small liquor bottles on one side and drinkware on the other—enabling them to “flash” their beverage selections around town. “Restaurant Day allows us all to test concepts we’re not sure about,” says Santala, “though the crazier, the better.”

By 2014, Helsinki Restaurant Day was welcoming over 700 pop-ups at once, and to this day, has not needed or secured permits or licenses, nor had any serious problems. “Police did make some inspections during the first year,” he says, “but they only issued two warnings—not tickets or citations—and [those] were to people who were standing around on the sidewalks drinking alcohol but not participating in Restaurant Day.” There are no known accounts of food poisoning, either. The whole thing seems practically impossible: a group of guerrilla restauranteurs joining forces for a day throughout a major city without any government interference. But it has worked—and then some.

“It’s brought something special to our city in many ways,” says Maija Hurmevirta, a restaurant manager who lives with her husband and 18-year-old daughter, Liisa, in the Helsinki suburb of Malmi. The couple happened upon the first Restaurant Day accidentally, she says. Impressed, they decided to open a pop-up of their own using the fruits that grow in the back garden of their home. Raparperitaisvas or “Rhubard Heaven” has appeared at every Restaurant Day since, with Liisa selling lemonade and pancakes from an old kiosk they had stored away in their garage, and Maija and her husband baking the made-to-order pancakes beneath the shade of lilac trees. “Our motto is ilo on ilmaista,” she says—joy at no cost.

Santala credits some of the event’s success with the autonomy of local government branches. “While the tourism department is aggressively promoting Restaurant Day, you’ve got the sanitation department saying, ‘we’re not so sure about this,’ so there’s no ‘official opinion.’” By the time city officials assembled to discuss the legality of Restaurant Day, it had already won both the prestigious Finland Prize as well as Helsinki City Library and Cultural Committee’s “Cultural Event of the Year.” In fact, Restaurant Day has garnered such a wonderful reputation in its originating city that even cruise ships docking in Helsinki are known to have begun timing their visits to coincide with it.

“We knew it was basically illegal—that we may even go to jail,” says Santala. “But we wanted to show that this idea of ‘proving you aren’t guilty before even having the chance to execute what you’re doing’ makes no sense.” Santala says it’s particularly interesting that Restaurant Day originated in Finland, which is part of the European Union, because “the Union has all kinds of laws and red tape. Strangely enough,” he continues, “Finland is one of the few countries that actually follows them.”

As word of Restaurant Day spread, so did its popularity. To date, Restaurant Day has been held in nearly 75 countries, including Italy, Peru and Pakistan, and there have been approximately 20,000 individual Restaurant Day pop-ups worldwide. Oslo, Norway, recently held its own Restaurant Day in February, and Montreal, Canada, is one of the most active Restaurant Day advocates, having adopted the event back in 2014 (in its case, however, special event permits are required). On a more local scale, the concept has even made its way across Finland—including tiny villages such as Rautjärvi in the country’s south-eastern corner, near to the Russian border. “We organized the ‘Smokesauna Pancake Cafe,’” writes local resident Arja Juuti, whose eatery specialized in large, thin pancakes cooked over an open fire, then served with homemade jams and a savory filling of cream cheese and smoked salmon. The pop-up’s name incorporates its location: a traditional Finnish sauna and its wooded surroundings, both belonging to family friends.

For many, Restaurant Day has become an entrepreneurial springboard. Santala says he knows of at least 15 restaurants, cafes and products that are a direct result of the event. One group of students worked with a local science lab to produce Ambronite—a drinkable “super-meal” of ingredients like nuts, berries, and spinach—for Restaurant Day, selling out of 200 of them in just two hours. This led to a lucrative Indiegogo campaign, and ultimately a bonafide business.

Then there’s Santala’s younger sister and her boyfriend, both of whom he describes as “not the kinds of people who would normally be entrepreneurs.” Their first foray into Restaurant Day consisted of a “cake cafe” in their apartment. “A woman stopped by and absolutely loved what she tasted,” says Santala. “She then asked my sister if she could bake a cake for her daughter’s wedding. The next time my sister opened her cafe, some residents of her building requested a cake for a meeting they were hosting the following week.” These days, she is studying to be a teacher while running a part-time catering business on the side.

One of Restaurant Day’s most impressive success stories is B-Smokery, run by a group of Helsinki filmmakers. According to Santala, as they became interested in the idea of Restaurant Day, they bought four large smoking pans from Germany and began running an outdoor barbecue. “I’ve seen these guys smoking meat in -20 Celsius,” he says. “Now that’s dedication.” Today, along with B-Smokery Productions, they run a dedicated eatery serving baby back ribs, brisket and sausage within the city’s Abattoir, a mix of outdoor food stalls and stationary indoor eateries.

Last May, Restaurant Day celebrated its fifth anniversary, and with it came a major change. “We thought, everyday and any day should be Restaurant Day, if you like,” says Santala. While many locations worldwide were happy to take the reigns, establishing more than 1,000 Restaurants Days of various sizes in the first eight months, others preferred a more global approach. To accommodate both, Santala and his team have designated the third Saturday in May as International Restaurant Day—though the encouragement to host your own events still remains.

Whether an independent or coordinated event, Santala believes Restaurant Day has changed how locals within numerous communities interact and has tapped into a creative consciousness that seems only to strengthen as it grows.

“Not only has Restaurant Day and our little pop up been increasing our social capital,” says Hurmevirta, “but it’s also inspired us to look for other small ways to spread the joy.”