On Sept. 1 fifteen years ago, all across Russia families were beginning to celebrate the First Bell — the start of the new school year: children lined up in their school best, parents and grandparents beamed and took photographs, and school principals gave speeches to welcome the students. The scene was repeated in every city and town in the country.

But at a few minutes after 9 a.m. in the small city of Beslan, North Ossetia, the festivities were shattered when dozens of armed men and women descended on School #1, shooting into the air and at anyone who tried to stop them from pushing more than 1,200 children, teachers and parents into the small school gym. Instantly the terrorists wired the auditorium with bombs, broke all the windows — to prevent the use of any gas — and shot dead in front of the hostages two fathers who protested.

The group was Riyad-us Saliheen, a force of suicide attackers under the Chechen warlord Shamil Basayev. They had driven into Beslan that morning from Ingushetia — in part by bribing the officers at checkpoints, it would be revealed — and had two main demands: that all Russian forces be withdrawn from Chechnya, and that Chechnya be granted independence.

Soon after the siege began, the militants pulled out about 20 men and took them in the hallway to be shot. A bomb on a woman terrorist’s belt exploded (possibly detonated by one of the terrorists because she objected to taking children hostage), killing a number of attackers and hostages. The militants killed the survivors and tossed their bodies in front of the school.

And so the siege began. The hostages were not given food or drink. Children stripped down to their underclothes, sweltering in the extreme heat, sometimes drinking their own urine to keep from completely dehydrating. While a crisis team was set up in Moscow, several negotiators entered the school, including the pediatrician Leonid Roshal, who had helped at the Nord-Ost siege in Moscow (2002), and Ruslan Aushev, ex-president of Ingushetia, who managed to lead out 11 nursing mothers and 15 infants. Anna Politkovskaya was flying in to escort Aslan Maskhadov, then the president of the self-proclaimed Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, to negotiate, but she was apparently poisoned on route. Neither she nor Maskhadov made it to Beslan.

According to most accounts of participants, the Riyad-us Saliheen group was open to negotiation, providing a telephone for contact and a video cassette with demands. But in Moscow the newscasters, who were maintaining that there were only 354 hostages, announced that the telephone didn’t answer and the video cassette was empty. Media, both Russian and foreign, flooded into Beslan, reporting events minute-by-minute, although Russian state media coverage was decidedly less detailed than the non-governmental stations. In Russia, life seemed to stop. In every house and apartment, the sound of news from radios and televisions drifted out of the windows.

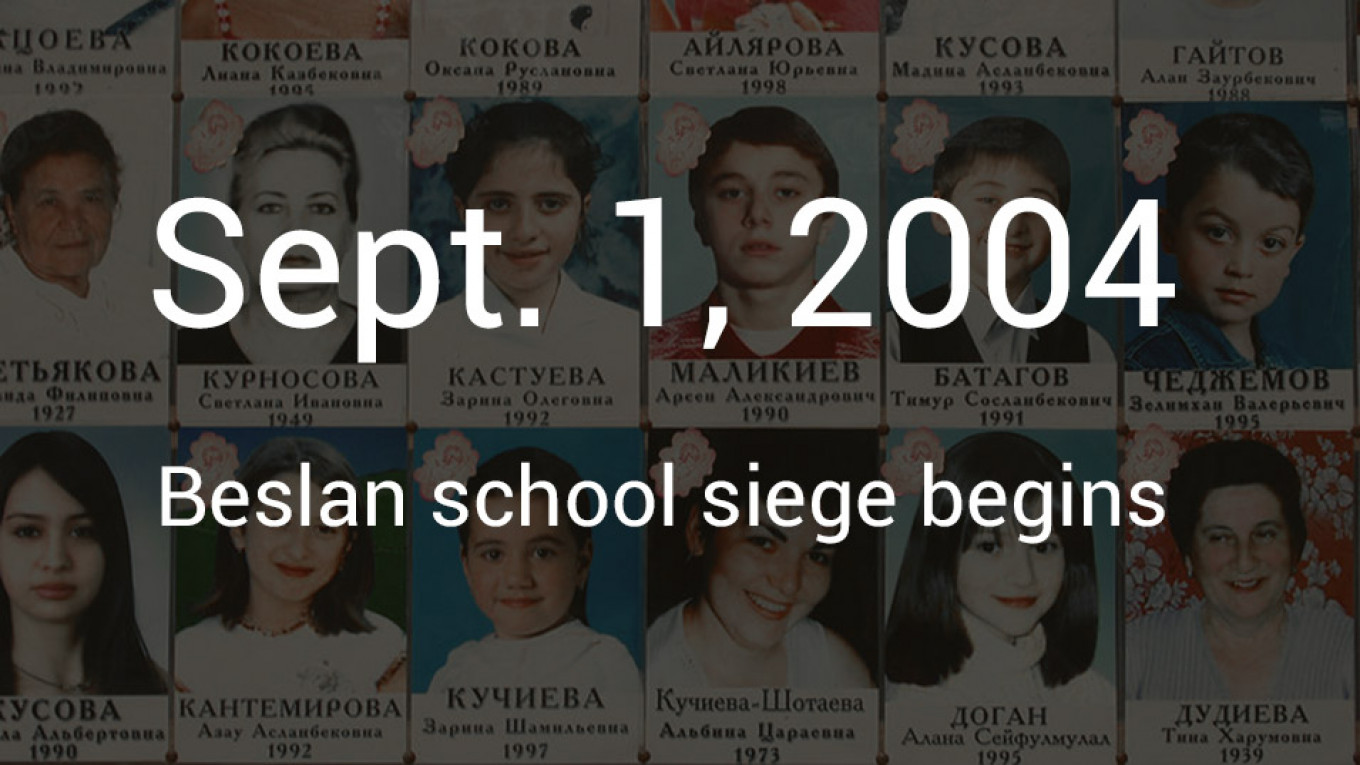

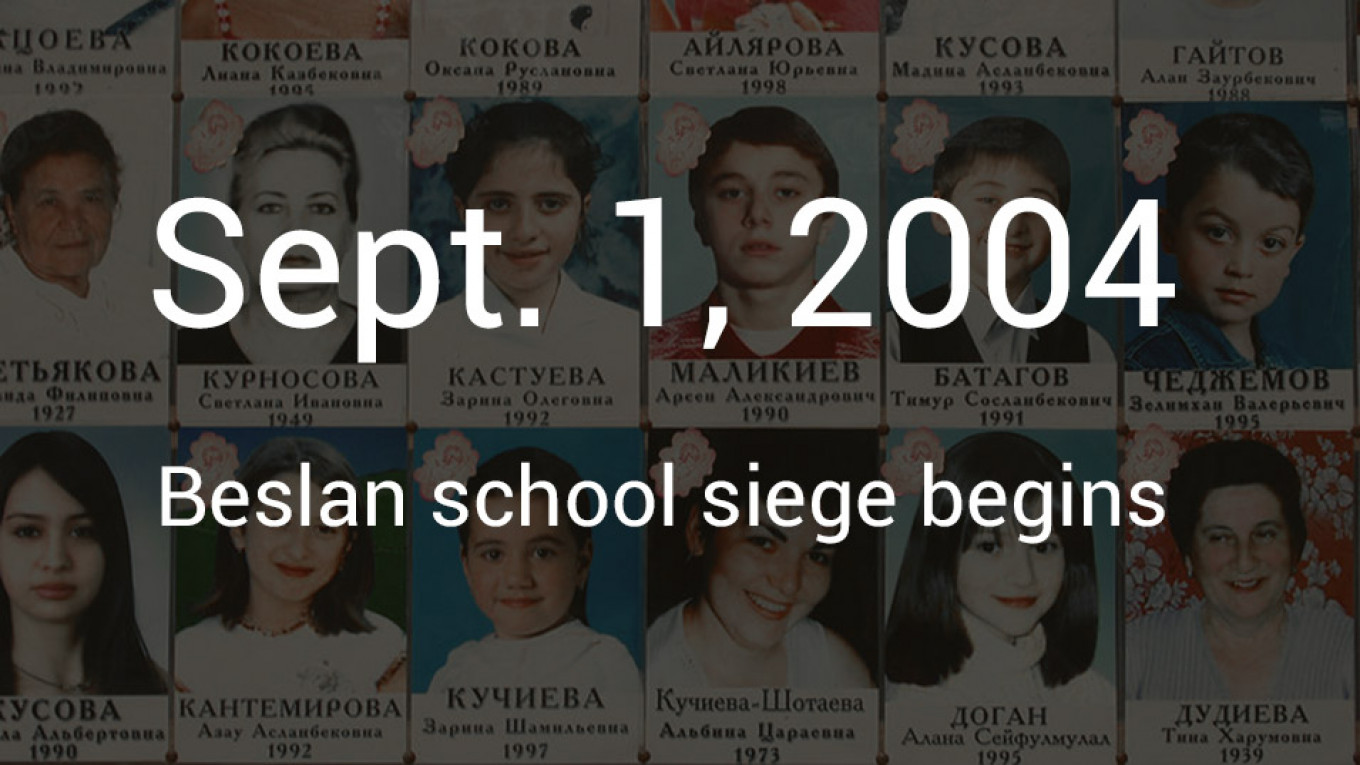

On the third day the terrorists allowed medics to gather up the dead bodies lying in front of school. As that was underway, there were a series of explosions, and the huge force of Russian troops stormed the building. The wired roof over the gym exploded, burst into flames and collapsed on hundreds of hostages. The troops used tanks, incendiary devices, rockets, and other weaponry. In the end, 334 people died, including 186 children. All the militants but one were killed; the survivor gave testimony about the event and is now serving a life sentence.

Beslan has never really recovered. Unconvinced by the official version of events — in particular, that the storming was in response to shots fired out of the school — 89 families brought their case to the European Court of Human Rights. In 2017 the court ruled that the Russian government had been negligent for not acting on evidence of a likely attack on a North Ossetian school, for using “indiscriminate force,” and for other failures to protect their lives of Russian citizens. The court ordered Russia to pay almost 3 million euros in damages.

Almost immediately after the event, changes were made to the state system. President Vladimir Putin signed into effect laws that eliminated direct election of governors and single-mandate parliamentary districts. Laws gave law enforcement agencies new powers to fight terrorism. Crackdowns on the media and non-governmental organizations would ensue.

The documentary in Russian below provides a full account of the event.