The basketball is scuffed and scruffy, its provenance unknown, its rotating tricolors, when in motion, creating a mesmerizing pinwheel effect.

This sacred relic—an official game ball used by the late, lamented American Basketball Association—reposes behind glass at the new National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. It came to symbolize the ABA, a renegade professional league that ditched the traditional brown ball almost as an act of youthful defiance.

The ABA was launched exactly 50 years ago when 11 owners ponied up franchise fees of at least $5,000 to get into a league whose purpose—not unlike many of today’s internet start-ups—was to force an eventual merger, in this case with the National Basketball Association. The kaleidoscopic ball had been ordered up by the nearsighted commissioner, NBA legend George Mikan, who said he could barely see its drab counterpart in a dimly lit arena.

The Audacity of Hoop: Basketball and the Age of Obama

Equal parts biographical sketch, political narrative, and cultural history, “The Audacity of Hoop” shows how the game became a touchstone in Obama’s exercise of the power of the presidency.

And the neighborhood gyms in which ABA teams often competed were pretty much all dimly lit. In the 1997 ABA documentary Long Shots, Lloyd Gardner, trainer for the Kentucky Colonels, remembered crowds so small that you could count the house in the time it took to play the national anthem. “There were a bunch of people disguised as empty seats,” recalled the league’s first big star, Connie Hawkins.

In an attempt to challenge the NBA’s position as the basketball league, the ABA adopted a frantic, streetwise style of play redolent of improvisational theater. “The imperative was entertainment,” says Alexander Wolff, author of The Audacity of Hoop.

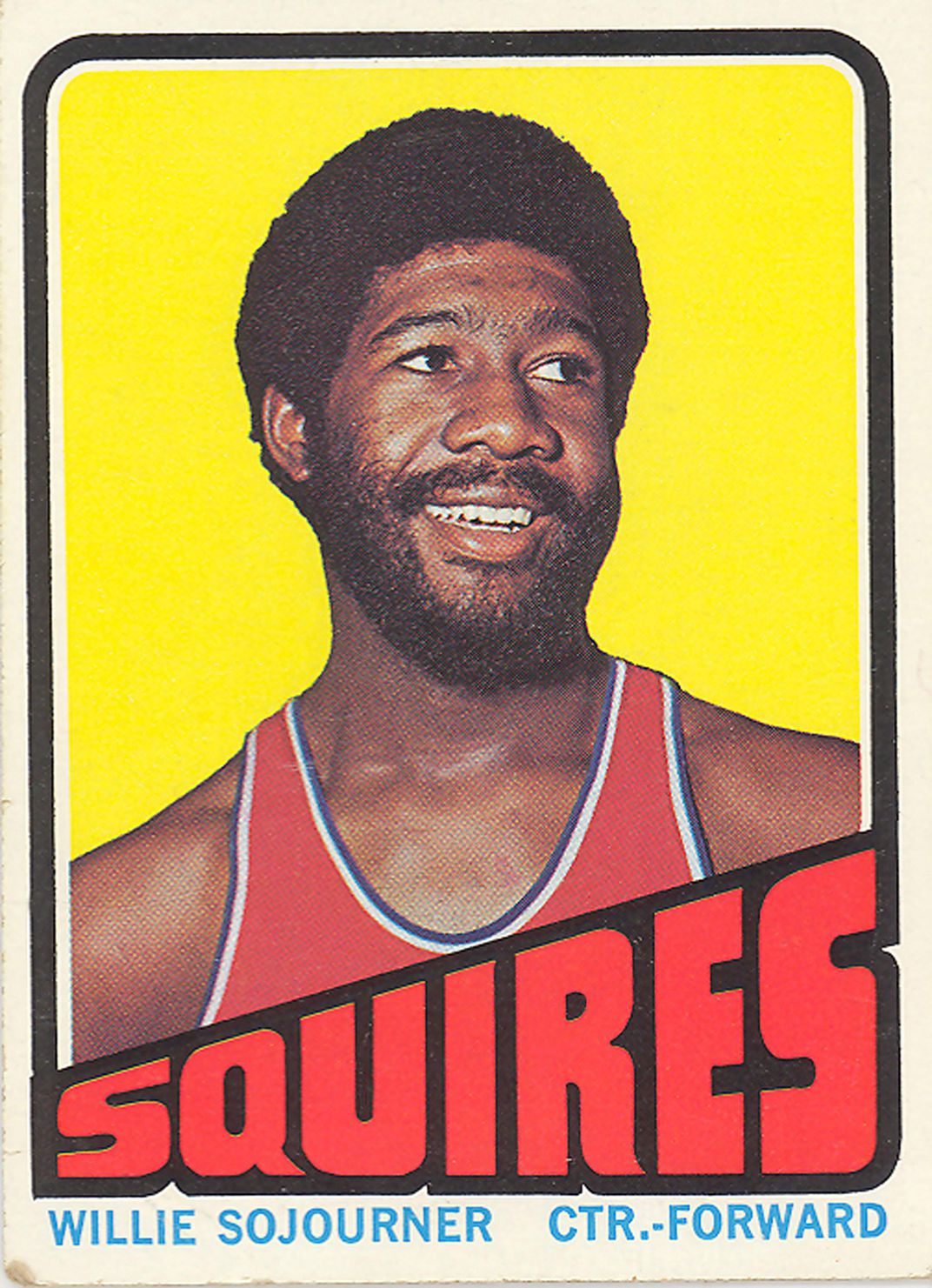

Unfortunately, the league never got much in the way of exposure. With no national TV deal, much of the revenue came from ticket sales. And to sell tickets, ABA players let every kind of freak flag fly—from Afros on their black players to handlebar mustaches on their white ones. No Afro was more bountiful than the “Mushroom Cloud” that crowned Darnell (“Dr. Dunk”) Hillman. It was Hillman who taught Julius (“Dr. J”) Erving—he of the jukes, jams and astonishing midair moves—to groom an Afro for maximum size and aerodynamics.

Jack McCallum, whose book Dream Team chronicles the 1992 U.S. Olympic men’s basketball squad, says the ABA was the outlaw game and not just because it employed players the NBA had blackballed and adopted rules that effectively discouraged effort on defense. “The senior circuit seemed constrained when compared to the free-flowing ABA, which gave us off-court apparel right out of Shaft, slam-dunk contests, a radical the world-is-ending three-point line (which the NBA derided, then adopted) and a jazzy up-tempo style that flew in the face of bounce passes, back doors and boxing out.”

These extemporaneous performers (Travis “The Machine” Grant, George “The Iceman” Gervin, Levern “Jelly” Tart) were often as colorful as the balls they dribbled. No one embodied the rebellious spirit of the ABA—and the excess of the disco era—more than Spirits of St. Louis power forward Marvin “Bad News” Barnes. He was nothing if not resourceful. After a long night of revelry in New York, he overslept and failed to make his flight to Virginia. No problem: He arranged for a private plane and swanned into the arena during warm-ups, two women in tow, clutching a bag of burgers. Flinging open his ankle-length mink coat to show off his Spirits’ uniform, he announced, “Boys, Game Time is on time!” Though benched for the opening tip and most of the first quarter, Bad News ultimately contributed 43 points and 19 rebounds.

The vast majority of ABA franchises were financially stressed. Teams that didn’t move to other cities often vanished into the ether. Four ABA teams—the San Antonio Spurs, Indiana Pacers, Denver Nuggets and New York (then New Jersey and now Brooklyn) Nets—survived, when, in 1976, the league was finally bagged as a takeout order for the NBA.

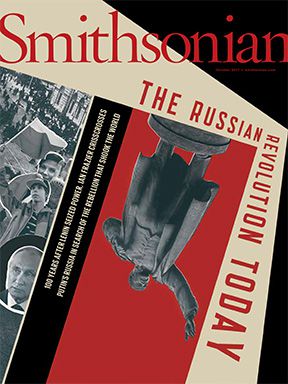

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $12

This article is a selection from the October issue of Smithsonian magazine