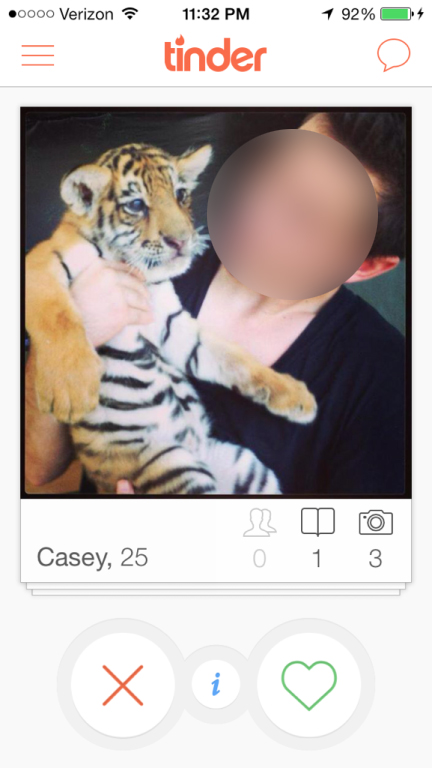

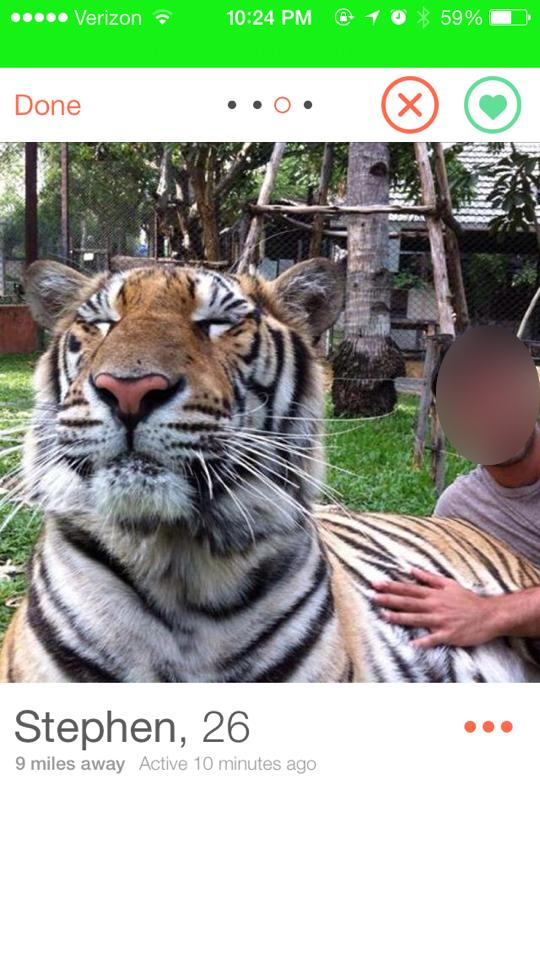

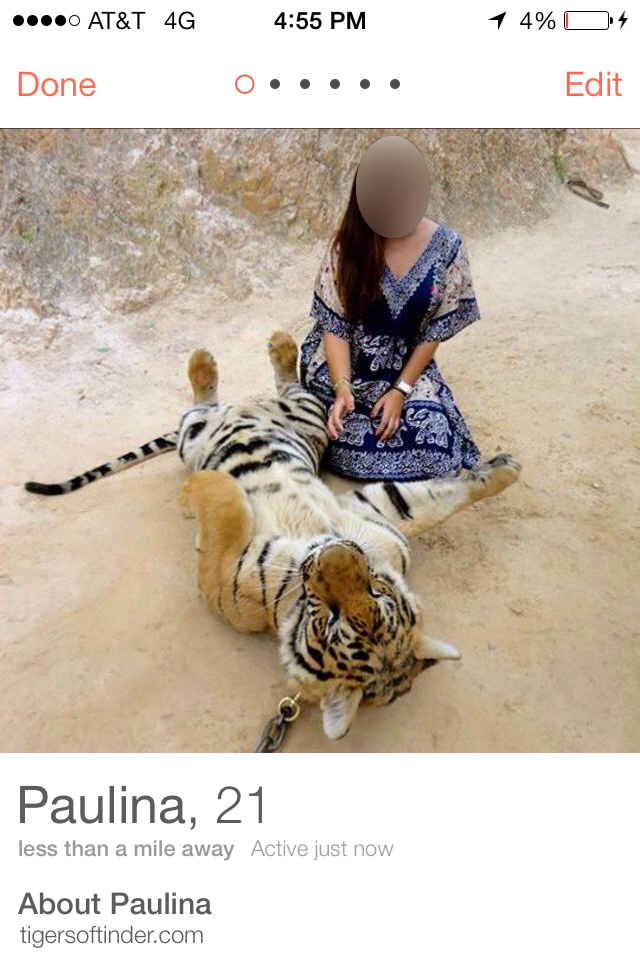

If you’ve ever prowled an online dating site, you’ve likely seen them: pictures of potential mates cuddling with an adorable tiger cub or petting a grown tiger in a cage. These photos have become so popular that they’re nearly as cliched as the stereotype of Tinder guy holding a fish; Tumblr feeds like Tigers of Tinder and Tinder Guys With Tigers have popped up to showcase users hanging out with the big stripey cats.

Related Content

What goes into those photos, though, isn’t very cute and cuddly. Last year’s exposé of Thailand’s notorious Tiger Temple, where 137 tigers were confiscated by wildlife officials, alerted many that the animals that grace these photos are often caged, drugged and tied down for our viewing and petting pleasure. That’s why, earlier this month, Tinder issued a blog post asking its members to “take down the tiger selfies” after receiving a letter from animal rights group PETA.

“We promise that your profile will be just as fierce without the drugged animals,” the post read. It added that Tinder would donate $10,000 to Project Cat, a tiger protection partnership between Discovery Communications and the World Wildlife Fund, in honor of International Tiger Day.

It may seem obvious that keeping tigers drugged and chained to make them more amenable to selfie-taking is messed up. But it’s worse than you think. This practice harms not only individual tigers, but conservation efforts to protect the endangered wild cats worldwide, says Marshall Jones, a senior conservation advisor at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute who works with tigers and other big cats. “Almost everything about this is wrong,” says Jones.

First, consider that there are a limited number of ways to make an adult tiger calmly lie down for a photo with a human—and none of them are good.

Harsh training regimens might condition cats to follow commands; undercover investigations have found that trainers at Thailand’s Sriracha Tiger Zoo keep tigers in line with whips, deprive them of food and prod them with sticks to make them roar. But even trained tigers wouldn’t be safe with the public. That’s why, according to PETA and other organizations, places that market tiger photo ops often turn to sedatives.

Sedatives can be used under responsible conditions: Minnesota Zoo associate veterinarian Rachel Thompson, who works with the zoo’s four tigers, says that her zoo relies on them to anesthetize tigers when the animals need medical attention. In zoos, these sedatives—a combination of the known anaesthetics ketamine, medetomidine and midazolam—are usually delivered by dart.

In some cases, animals are trained to press a shoulder or hip to the mesh of their enclosure so they can receive an injection. These trained “medical behaviors” are designed to reduce stress for the animal, says Thompson. “When used properly, I wouldn’t anticipate any long term effects” from sedatives, she says.

But nobody knows exactly what kind of drugs tiger attractions are using, nor in what quantities, says Jones. Long-term abuse of sedatives could lead to a host of side effects, such as changes in breeding behavior and problems with eating. “Imagine drugging an animal day after day,” says Jones. “They can’t live long lives and they probably have all sorts of side effects.”

While Thailand and its infamous temple have been the focus of the most recent tiger selfie controversies, there are plenty of places in the United States where people can and do take photos with the big cats. There are an estimated 5,000 tigers in private hands in the United States. That’s 10 times more than the number in accredited zoos and other institutions—and more than the some 3,900 tigers found in the wild globally.

Many of these privately owned cats are in roadside zoos, which often feature tiger petting and photo attractions, says PETA supervising veterinarian Heather Rally. These kinds of attractions often say they’re raising money for conservation initiatives, or claim to be otherwise helping conserve tigers. But in reality, they go against nearly every ideal of conservation. “Reputable zoos—that is, [accredited] members of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums—have guidelines,” says Jones.

These guidelines are governed by each species’ individual Species Survival Plan, which carefully monitors the wellbeing, breeding and overall genetic diversity of the captive population. Minnesota Zoo oversees the SSP for North American tigers, which are moved from one AZA-accredited zoo to another on the basis of their plan. “With wild animals, the whole idea in zoos is to maintain the gene pool and to keep the ‘wild gene,’” Jones says, in part so captive tigers are one day fit to be released into the wild.

But most of the tigers in America aren’t part of the SSP, says Jones. And at shoddily regulated roadside attractions, “nobody can really say how the tigers are being cared for”—how they’re being held, what they’re eating and whether they’re receiving vet care.

Regardless of how sedated the tigers are, Thompson adds, tiger attractions anywhere pose a risk to both visitors and handlers. Zoo vets like her might sedate tigers for a few different reasons—like to calm them down for transport or if construction was going on near them—but always just until the stressful event was over, and always on the other side of a barrier. “These animals are very large, they’re very strong, and their instincts are very powerful,” she says. “I don’t think we can predict what the behavior will be when they’re not allowed to be at full capacity mentally.”

“No reputable zoo is going to engineer a situation where people would be in contact with dangerous wild animals,” adds Jones.

Of course, tigers today face many other threats beyond irresponsible Tinder users. Poaching continues to pose a major threat to tigers in the wild, thanks in part to the high demand for tiger body parts on China’s black market. But tiger petting zoos in other countries can also contribute to that dubious market, says Jones. “What happens after they die? Where do their parts go?” he asks. “Every part of the tiger is worth a lot of money on the black market.”

During the raid on Tiger Temple, wildlife authorities found more than just live tigers: they uncovered a freezer full of 40 tiger cub carcasses, 20 more preserved in formaldehyde, and numerous body parts and charms made from tiger skin. Every time someone poses for a tiger selfie, Jones says, they’re “supporting an industry that causes suffering to tigers and may contribute to the decline of wild tigers, because every time parts go into the illegal black market … it just fuels the demand.”

The practice can also contribute to the pet tiger industry. In the U.S., most petting zoo tigers tend to be young cubs, Rally and Jones say. For instance, Doc Antle’s Myrtle Beach Safari in South Carolina advertises that visitors can “interact with tiger cubs”; Dade City’s Wild Things in Florida advertises petting and cuddling sessions with baby “Tigers, lions, jaguars, leopards or panthers.”

In most cases, these cubs are “forcibly taken from their mothers” at a young age, says Jones. The idea is to get them acclimated to humans early so that they can be handled. Besides being psychologically traumatic, Rally says, this early separation interferes with their natural development and may cause them serious health problems. Cubs “can’t even regulate their own temperature for the first four weeks of their lives,” she says. “They don’t have fully developed immune systems for the first couple of months of life.”

Tiger cubs reach adult size within about a year and a half. After that, if they’re in the U.S. they usually end up as somebody’s pet. As you might expect, “the quality of care by private owners varies tremendously,” write conservationists Philip J. Nyhus, Ronald Tilson and Michael Hutchin in Tigers of the World: The Science, Politics and Conservation of Panthera tigris. Some pet tiger owners are responsible and provide “adequate care,” but “another subset provides inadequate care or abuse their animals or are interested only in illegally trafficking tigers for commercial gain.”

…..

The ready availability of tigers for selfie opportunities might create the illusion that the cats are abundant. In reality, tigers are considered endangered, and populations around the world are decreasing. “Four of nine subspecies have disappeared from the wild just in the past hundred years,” writes the AZA. International Tiger Day is intended to draw attention to the plight of these majestic wild cats; meanwhile, tiger selfies only highlight tigers in captivity, kept in conditions unlikely to help them ever return to the wild.

With that in mind, Thompson reminds online daters that there’s no safe and ethical way to directly interact with tigers unless you’re a zookeeper or conservationist. Fortunately, you can always catch some stripey cuteness on non-intrusive tiger cams: both Minnesota Zoo and Oklahoma City Zoo have cameras trained on their tiger families right now. As for your dating profile, maybe just stick to selfies with your dog.