Peter Voulkos was a game changer for modern ceramics.

Related Content

The Renwick Gallery’s exhibition “Voulkos: The Breakthrough Years,” documents the 15 years of groundbreaking experimentation that enabled the ceramicist to redefine his medium and transform the craft into fine art.

“Voulkos is the man who punches his pots,” says Andrew Perchuk, deputy director of the Getty Research Institute and one of a trio of the exhibition’s curators. “He inverted traditional ideas of how a well-made piece of ceramics is constructed,” explains Perchuk, describing the unorthodox methods that Voulkos adopted including slashing, gashing, and over-firing his work.

Born in Montana of Greek immigrant parents, Voulkos got his start in ceramics after World War II while attending college on the GI bill. At the University of Montana, he studied under the renowned art professor and functional ceramicist Frances Senska and developed into a masterful craftsman praised for his throwing technique. Soon, he was selling his own dinnerware at leading department stores and winning awards.

But by 1955, Voulkos abandoned these functional pieces and began experimenting with increasingly unconventional methods. Among the influences he cited for inspiring his new direction were Japanese pottery, the artworks of Pablo Picasso, Abstract Expressionist painters like Franz Kline, as well as avant-garde poets and writers.

“He was very successful within a limited framework, and then he threw it all away,” says curator Glenn Adamson, senior scholar at the Yale Center for British Art who, along with Perchuk and associate curator Barbara Paris Gifford, originated the Voulkos exhibition at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City.

The ceramics exhibition is offered next to a retrospective of another mid-century California artist, enamelist June Schwarcz whose hallmark is innovation and abstraction.

“I love the point counterpoint of June being virtually self-taught learning electroplating and sandblasting, and then you have Peter Voulkos who is this absolute master of wheel-thrown vessels who starts breaking it all apart,” says Robyn Kennedy, chief administrator at the Renwick Gallery who helped to coordinate both shows.

“The Breakthrough Years” features 31 examples from Voulkos’ early experimentation, including three paintings on canvas. Organized in chronological order, the trajectory of his work is apparent.

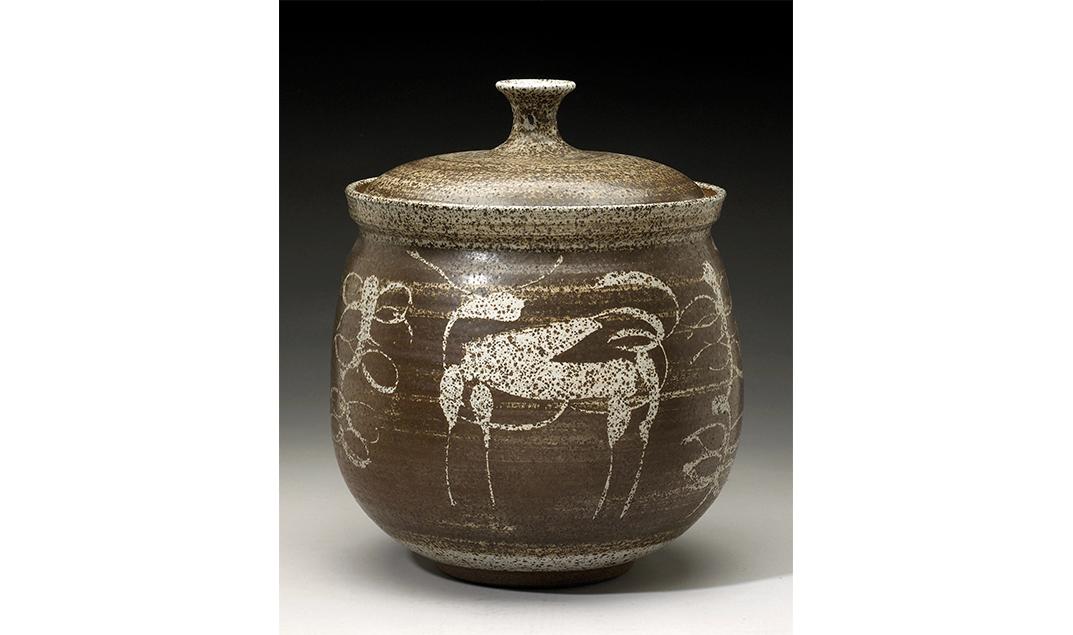

The section entitled “Early-Works, 1953-56” showcases objects that are still recognizably utilitarian. However, the rest of the show highlights his deconstruction and innovation.

According to Perchuk, the Rocking Pot is a seminal early work that demonstrates Voulkos’ break with traditional ceramics. It is wheel-thrown, but then turned upside down, with holes gouged into it. Crescent shaped slabs are placed through some of the holes, and the entire pot sits on rockers, seemingly to defy the tenet that a well-made pot does not rock on a flat surface.

Adamson revealed that this piece had served for years as a doorstop in Voulkos’ studio, and the artist had dubbed it the “goddamn pot” because he knocked in to it so frequently.

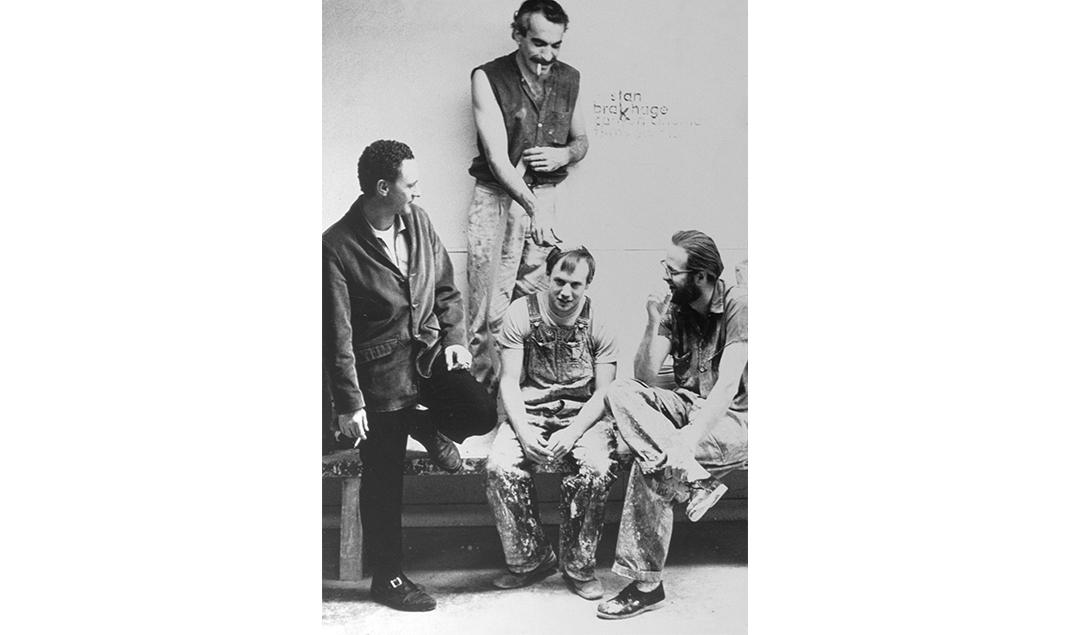

In 1957, Voulkos joined the faculty of the Otis College of Art and Design, a famed Los Angeles art school where instead of lecturing or demonstrating, he just worked alongside his students. Perchuk described how class meant jumping into cars to drive throughout the city exploring building construction sites as well as new sculpture and paintings appearing in local galleries and museums.

He surrounded himself with an all-male posse of students and colleagues who would work through the night, fueled by coffee, beer, cigarettes (and possibly other smoked substances) as jazz or flamenco guitar blared in the background.

While at Otis, Voulkos created an industrial-capacity studio with fellow artist John Mason so they could make pieces on a much larger scale. They modified their wheel with extra horsepower to handle up to 100 pounds of clay and created a new clay mixture that would offer more structural integrity. They built an oversize kiln that could be loaded with a forklift. The bought a second-hand dough mixer from a bread factory to knead the clay and humidifiers designed for fruit warehouses to keep the clay from drying out.

“As they were scaling up in the first year and a half, none of their pieces survived the firing process,” says Adamson. But eventually, Voulkos devised methods for interior and exterior architectural elements that would support each other and allow for colossal pieces.

After a disagreement over his teaching style with school director and painter Millard Sheets, Voulkos left Otis in 1960 for a job at the University of California, Berkeley. There he took up bronze casting, which also took his ceramics in a different direction.

“He was not just playing around in different media, but also mastering them,” says Adamson. “He was feeding his imagination with a lot of different things, including cross-disciplinary energy.” Despite his new interests, Voulkos never abandoned ceramics or wheel throwing.

“The Breakthrough” exhibition includes archival footage of public demonstrations in which Voulkos creates pieces in front of audiences. ‘The films capture the monumentality and impressiveness of him at work and the speed and intuitiveness that he was able to bring to the process of groping with clay,” says Adamson.

The show closes with four haunting works from 1968 called “blackwares” whose black slip and metallic sheen give them a somber, funerary quality. The curators saw these pieces as marking the end of his exploration.

“These stacked forms as well as plates, and jars, would become the three formats that Voulkos would work on for the rest of his career without nearly the amount of experimentation and variation that we see in this breakthrough period,” says Glenn Adamson.

“He’s become the mature artist that he is now always going to be, and his days of sowing his wild oats as an artist have come to a close,” Adamson adds.

“Voulkos: The Breakthrough Years” continues through August 20 at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.