Daniil Kharms was born Daniil Ivanovich Yuvachyov in St. Petersburg in 1905. His father, a former member of the revolutionary group The People’s Will who had been imprisoned and exiled in his younger years, was a professor of philosophy.

Kharms first went to school in Tsarskoye Selo and then attended the German Peterschule, where he studied English and German. It was here that he came up with his pseudonym — word play of “harm” and “charm.” This was just one of his dozens of pennames, which included DanDan, Khorms, Charms and Shardam.

After a very short stint at the Leningrad Electrotechnicum in 1905, where he was expelled for not participating in “socially conscious activities,” and a course in film at the Leningrad Institute of Arts History, Kharms devoted his life to literature.

Kharms was very popular writer of children’s literature. From 1928 until 1941, he published stories and verse in children’s magazines and at the publishing house Detgiz under the writer and translator Samuil Marshak. He also published translations from German and English.

Kharms was at the forefront of the Russian avant-garde, forming and joining a variety of associations, such as the Association of Writers of Children’s Literature, the Leningrad branch of the All-Russian Union of Poets, and OBERIU (Association of Real Art), which he founded with a group of writers. Later he became a member of Left Art. “Poems aren’t pies; we aren’t herring” was part of the OBERIU foundation statement.

Only one of Kharms’ plays, “Yelizaveta Bam,” an absurdist tale of a woman accused of a crime she has yet to commit, was produced in 1928 to generally negative reviews. Only two adult poems were published in his lifetime.

In 1931 he was arrested as one of a group of “anti-Soviet children’s writers” and exiled to Kursk. Upon his return to Leningrad, he found it increasingly difficult to get his children’s works published. In 1941 he was arrested for a “defeatist attitude” about the war. It is believed that he feigned insanity to avoid execution. He was incarcerated at the Kresty Prison in Leningrad, where he died of starvation on Feb. 2, 1942.

His works were banned or forgotten for most of the Soviet period, and his writing would have been lost entirely had not his friend Yakov Druskin gone to his apartment during the Siege of Leningrad and filled a suitcase with works by Kharms and his fellow poet and friend Alexander Vvedensky. The works were hidden until the 1960s, and although some works by Kharms began to be published in the 1960s and 1970s, Kharms was not fully rehabilitated until the 1980s.

Daniil Kharms wrote plays, stories, vignettes, miniatures, and philosophical analyses. In his absurd world, there is little logic, no linear progression of events, and no sacred cows. He makes fun of every literary great from Pushkin to Tolstoy.

“I am interested only in ‘nonsense,’” he wrote, “only in that which makes no practical sense. I am interested in life only in its absurd manifestation.”

“The Connection”

Philosopher!

1. I am writing to you in answer to the letter that you are preparing to write me in answer to the letter I sent you.

2. A violinist bought himself a magnet and set off with it towards home. On the way, some delinquents attacked the violinist and knocked his hat off his head. The wind caught the hat and carried it down the street.

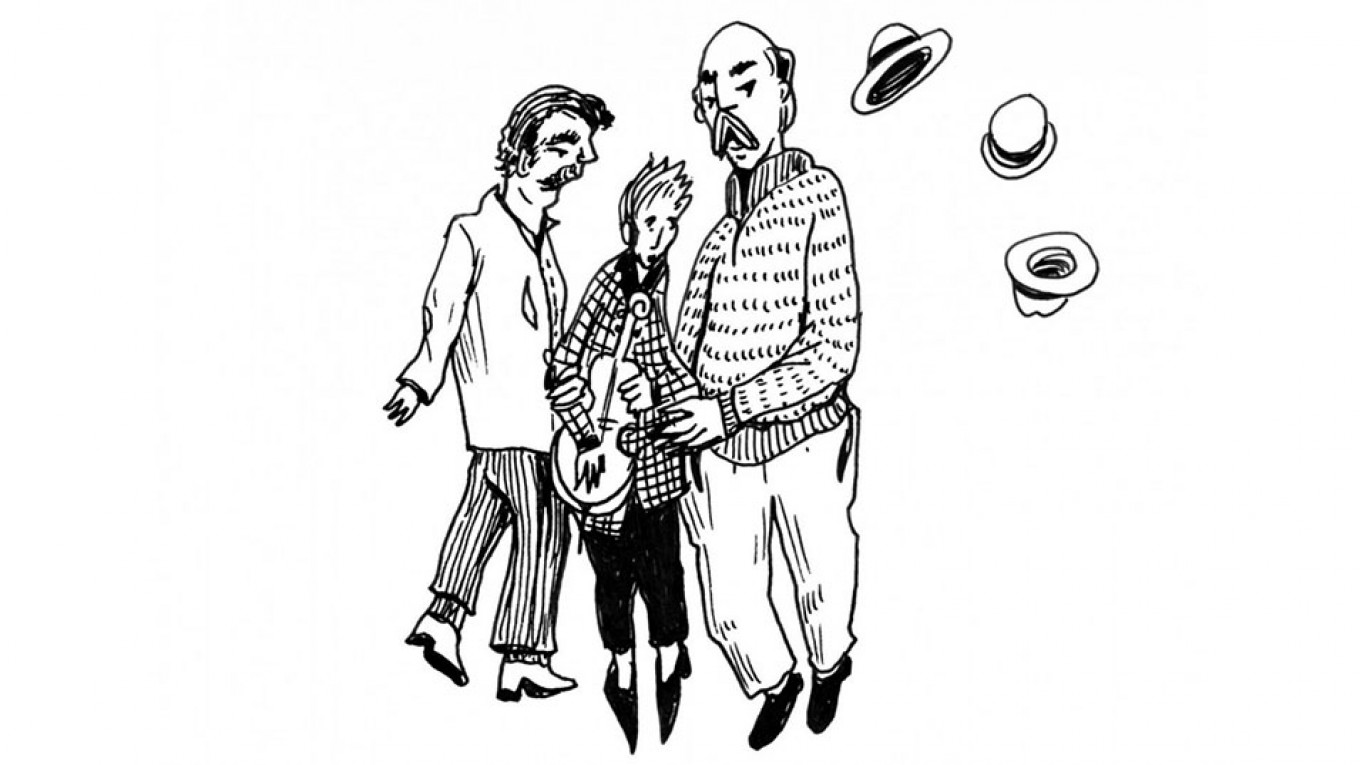

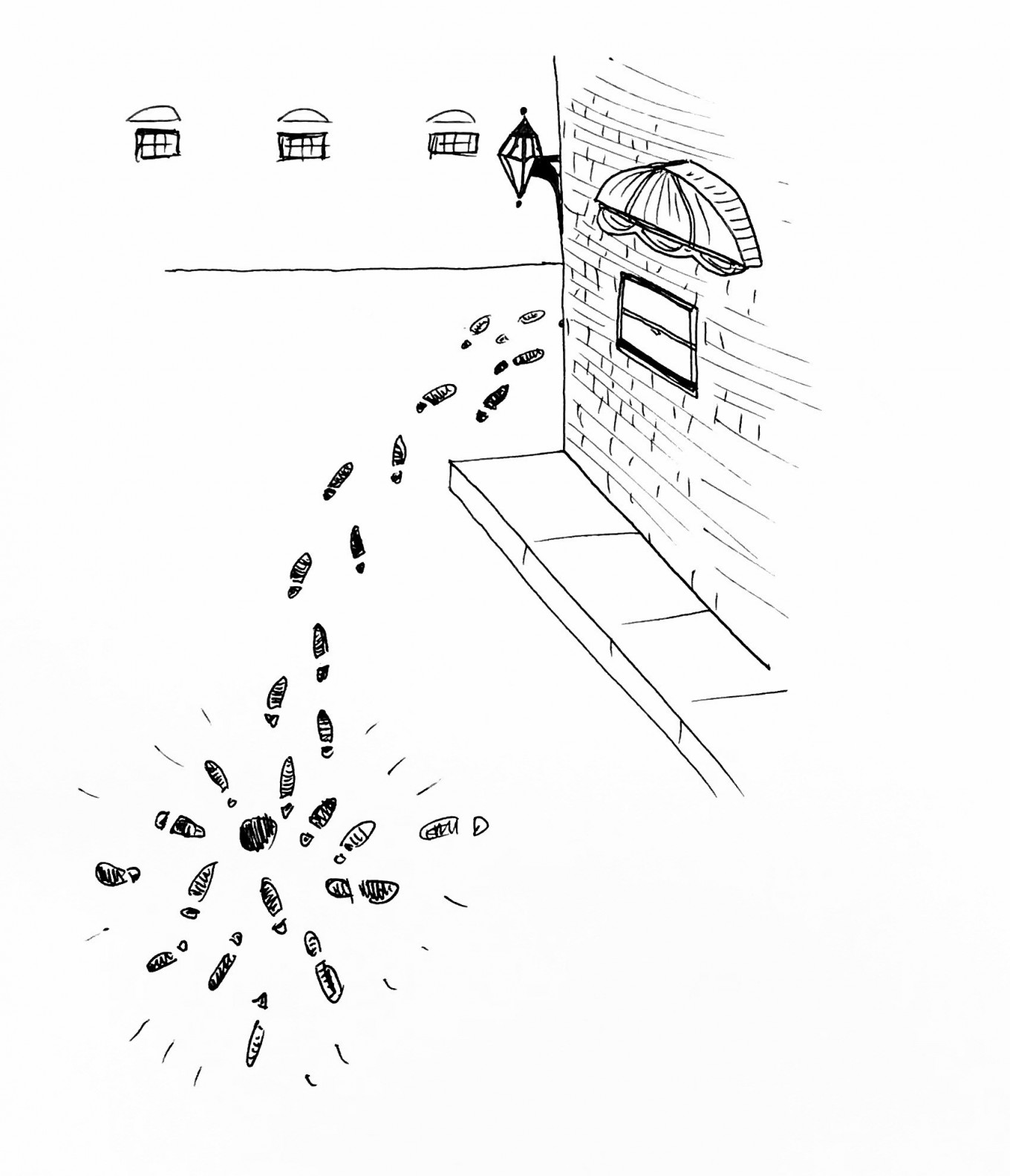

3. The violinist set the magnet down on the ground and ran after his hat. The hat blew into a puddle of nitric acid and decomposed.

4. Meanwhile, the delinquents grabbed the magnet and vanished.

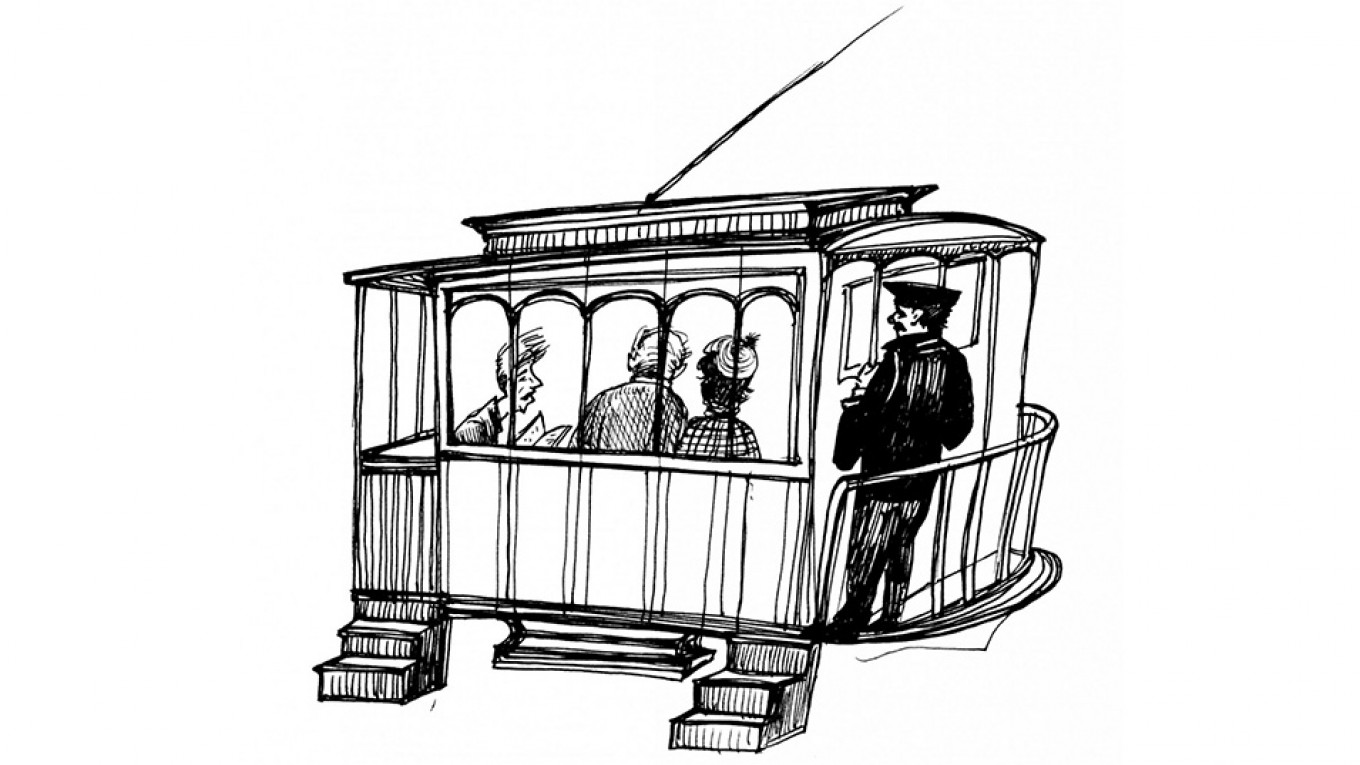

5. The violinist returned home without his coat and hat because the hat had decomposed in the nitric acid and the violinist, upset over the loss of his hat, forgot his coat in the tramcar.

6. The conductor on the tramcar took the coat to the flea market where he exchanged it for some sour cream, oats and tomatoes.

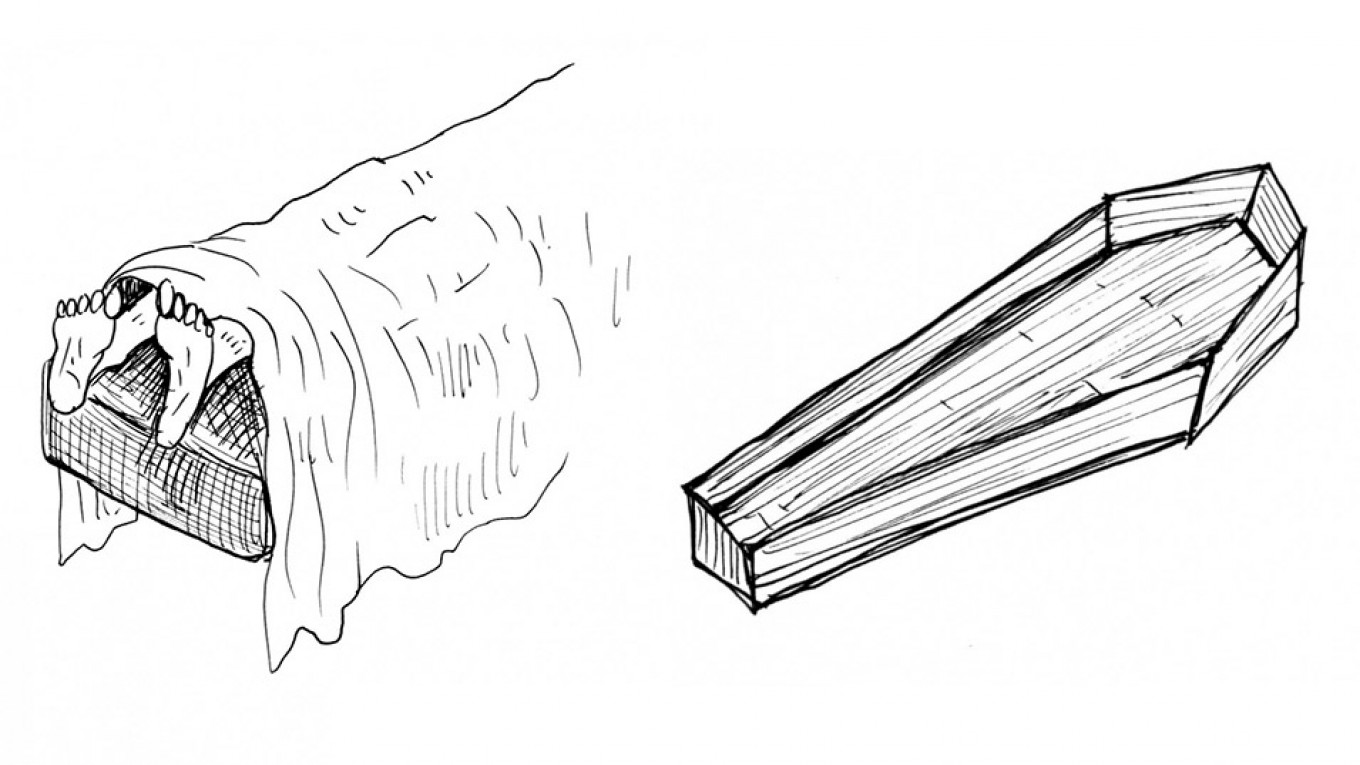

7. The conductor’s father-in-law ate too many tomatoes and died. The conductor’s father-in-law’s corpse was laid out in the mortuary but later, in a mix-up, some old woman was buried in place of the conductor’s father-in-law.

8. A white marker stating, “Anton Sergeevich Kondratyev,” was erected over the old woman’s grave.

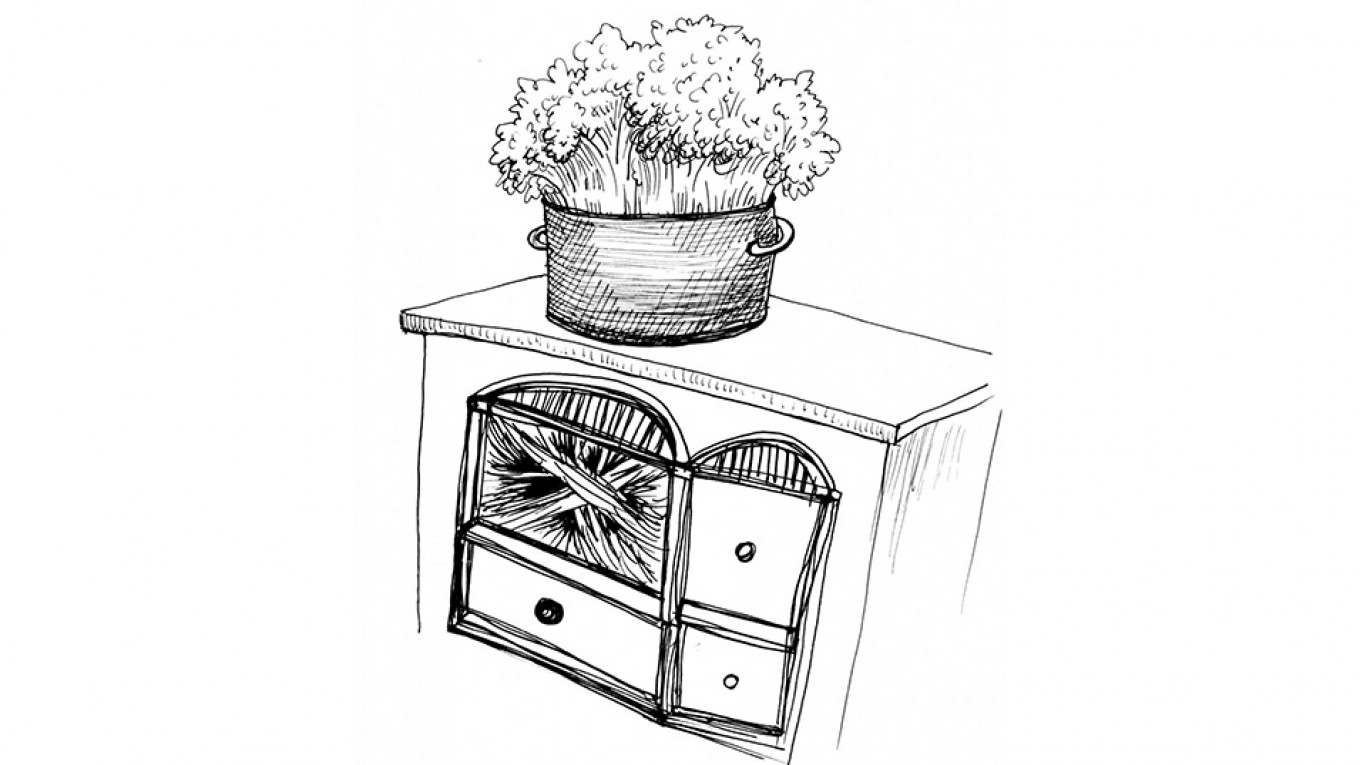

9. Eleven years later this marker was eaten through by worms and it fell over. The cemetery watchman sawed the marker into four pieces and burned it in his oven. The cemetery watchman’s wife boiled some cauliflower soup over the fire it provided.

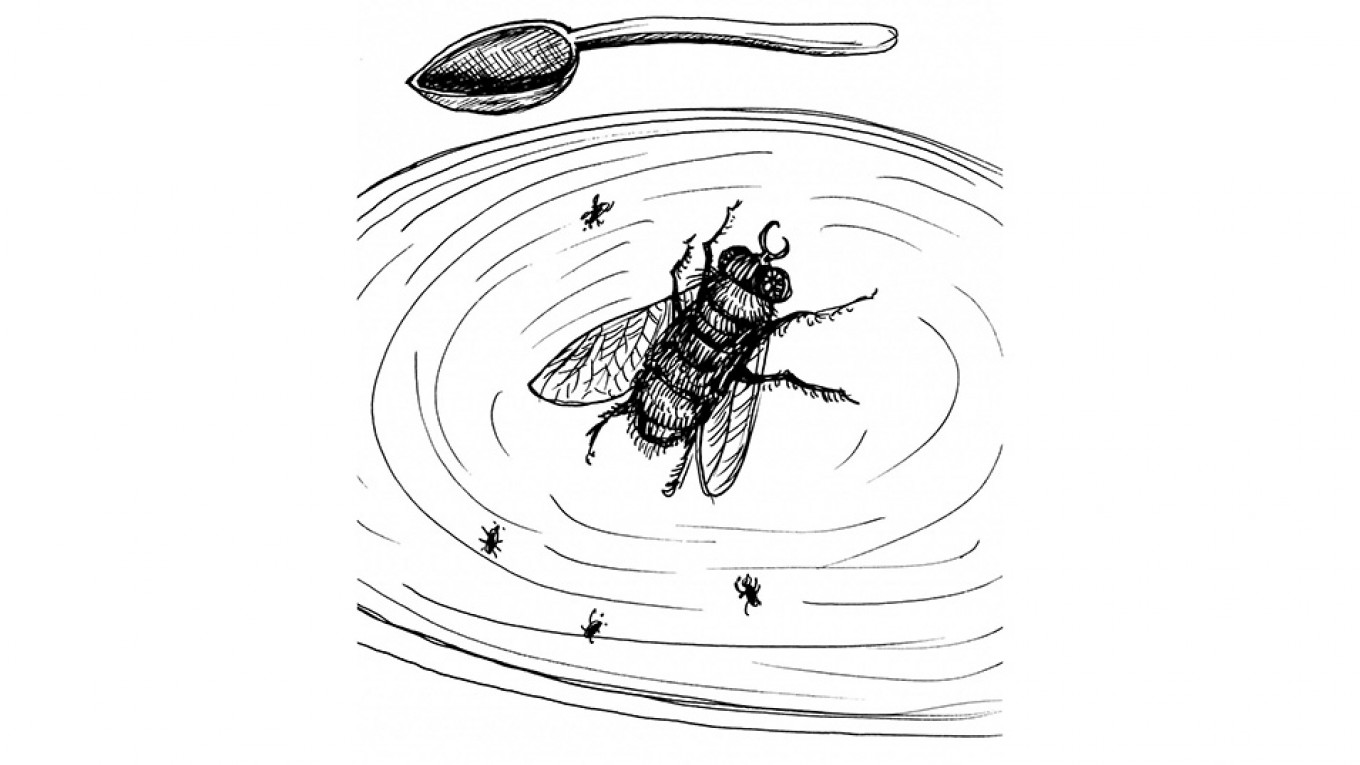

10. However, when the soup was ready, a clock fell off the wall right into the soup pot. They pulled the clock out of the soup, but there were bedbugs in the clock and now they were in the soup. They gave the soup to the beggar Timofei.

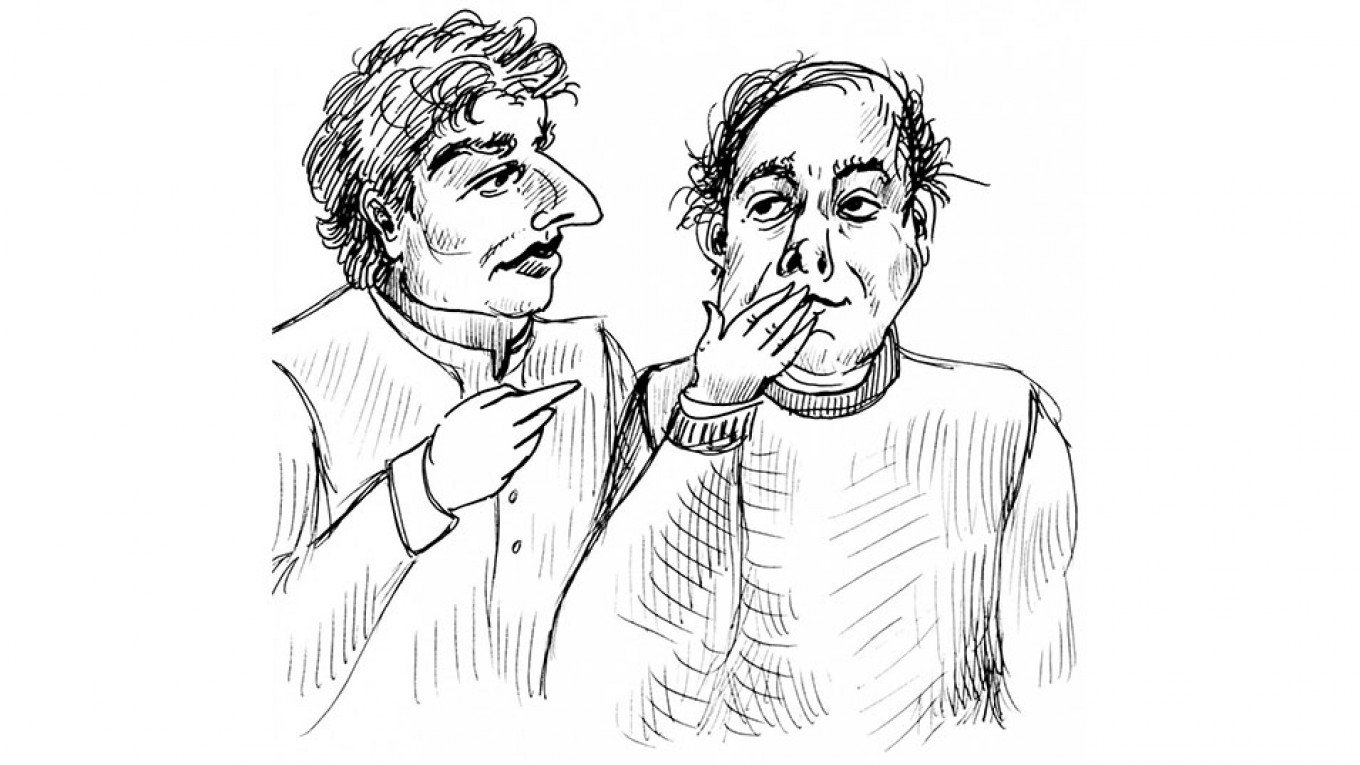

11. The beggar Timofei ate the soup with the bedbugs in it and told the beggar Nikolai of the cemetery watchman’s kindness.

12. The next day the beggar Nikolai came to the cemetery watchman and begged for alms. But the cemetery watchman gave nothing to the beggar Nikolai and chased him away.

13. The beggar Nikolai was so irate that he burned down the cemetery watchman’s house.

14. The flames leaped from the house to the church and the church burned down.

15. A lengthy investigation was conducted but no one could establish the origin of the fire.

16. A club was built in place of the former church and on the club’s opening day, a concert was held at which the violinist performed who had lost his coat fourteen years ago.

17. Sitting among the listeners was the son of one of the delinquents who, fourteen years ago, had knocked the hat from the violinist’s head.

18. After the concert, they went home in the same tramcar. But driving the tramcar right behind them was that very same conductor who once had sold the violinist’s coat at the flea market.

19. So there they are, riding late one evening about the city – in the car ahead are the violinist and the delinquent’s son; right behind them is the tramcar driver, the former conductor.

20. They all ride on but none of them know what connection there is among them, nor will they know until they die.

***

John Freedman is a translator, writer and theater critic who wrote a column for The Moscow Times for 24 years.

Frances Cannon is a writer and artist who is currently teaching creative writing and visual arts at two colleges in Vermont. They are collaborating on a book of works by Daniil Kharms.