You’ve probably heard of “baby face”—that dubiously complimentary term for someone who looks greener than their years, and which Merriam-Webster defines as “a face that looks young and innocent.” But you may not know the canine equivalent, “petface.” Similarly, it refers to the puppy-like features common to certain breeds of dogs: for instance, French and English bulldogs, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and pugs. With their awkward shuffle-gait, adorably large heads and bulging eyes, they’re the quintessential fur babies.

Related Content

Unlike youthful-looking humans, however, these dogs have juvenile traits are systematically built into their DNA through centuries of rigorous breeding. That’s a problem, because many of same traits that make these dogs “cute” also make them dangerously unhealthy. Along with their desirable features come higher than average predisposition to respiratory disorders, skin conditions, reproductive issues and eye injuries.

As the popularity of these dogs continues to skyrocket, it begs the question: is what’s good for us good for dogs? “People have been trying to educate people that these dogs have problems for a long time,” says Brenda Bonnett, a Canada-based canine epidemiologist and CEO of the nonprofit International Partnership for Dogs, which is dedicated to improving dog health and well-being. Yet so far, there’s no end to breeding in sight.

Consider the French bulldog. On the plus side, this charismatic small dog is relatively low-maintenance, doesn’t need a lot of exercise and sticks close to its owner; for many, the makings of a perfect pet. But the health issues associated with brachycephaly, which refers to dog breeds that have wide and flat skulls, means that they often require a higher-than-average amount of veterinary treatment. Moreover, they are forced to rely on humans for things as simple as having their wrinkles cleaned out and giving birth.

The American Kennel Club, which oversees dog breeding standards in the United States, stipulates that Frenchies should have “bat ears” along with “heavy wrinkles forming a soft roll over the extremely short nose.” But those bat ears are prone to infection, as the AKC itself notes. Thanks to their short faces, “Frenchies have less tolerance of heat, exercise and stress, all of which increase their need to breathe,” the guide continues, advising that Frenchie owners keep their pets cool and avoid strenuous exercise. It also notes that the dog’s wrinkles “can be prone to yeast and bacterial infections,” and should be cleaned regularly.

This is just one example of how extreme breed conformation can affect dog welfare and increase the reliance of brachycephalic dogs on human intervention. Yet while it’s long been known that purebred dogs tend to suffer from body shapes and genetic conditions that hurt their health and limit their day-to-day existence, it’s only now that we’re beginning to understand the long history and scientific mechanisms behind this suffering.

How We Got Here

The purebred concept emerged in the Victorian period, when middle-class city dwellers started regularly keeping pets for themselves and their children, rather than just farm animals. Around this time, the eugenics movement preached that it was possible to breed “pure” and ideal animals and humans.

“The systematic breeding of dogs emerged in the middle of the nineteenth century,” writes animal welfare scientist James A. Serpell in Companion Animal Ethics. “Although there were already clearly distinguishable breeds of dogs and other domestic animals before this, the new trend was characterised by conscious efforts to ‘improve’ domestic animals through controlled breeding.” While eugenics is now looked down upon in humans, it’s in many ways alive and well in the pet world. The ideal of “purebred” dogs as being somehow more valuable and desirable is still upheld by kennel clubs, breeders and those who buy them, says Bonnett.

Over time, purebred dogs became a form of status. “Toy” breeds, bred for companionship, also became even more popular. (The practice of keeping these tiny dogs is centuries old. The Kennel Club, which oversees British purebred dogs, says that “the Imperial Courts of China saw ‘sleeve’ dogs carried in the ladies’ kimonos–the Pekingese–while in Europe the white Mediterranean breeds, loved for their size, luxurious white coats and contrasting dark pigmentation, were carried around in ornamental baskets; they were the ‘toys’ of the ladies of the household.”)

A number of brachycephalic breeds are also classified as toy breeds by the Kennel Club: pugs, Yorkshire terriers, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and Pekingese among them.

The most important requirement for a purebred dog is that its entire pedigree–its whole family tree–is recorded in a stud book. The original idea was to only breed from the best. Ironically, this attempt at creating healthier, more ideal dogs actually paved the way for more—and more devastating—genetic diseases.

Breeding from only the same line means inbreeding, which results in a buildup of the recessive genes that cause common non-conformation-related brachycephalic dog diseases like heart disease and skin issues. It also diminishes genetic variability, which protects populations from being wiped out by one catastrophic event. In other words, this kind of breeding is a double edged sword: It means desirable features are kept, but undesirable disease-causing genes can also be fixed within the breed.

A 2017 study of insurance claims conducted by the American pet insurer Nationwide found that brachycephalic breeds face a more than 100 percent increase in the likelihood of claims for corneal ulcers and ocular trauma, a more than 80 percent uptick in the likelihood of claims for skin cancer and fungal skin disease, and a more than 100 percent uptick in claims for pneumonia and heat stroke. Some of these issues are related to conformation, or body shape; others are linked to inbreeding.

Along with the idea of genetic purity came the idea of conformational purity: that dogs could be bred to have an ideal conformation. Dog conformations today are at an extreme, driven by novelty as well as breed standards and demand from dog owners.

A series of images comparing breeds from 1915 to 2015 demonstrates this transformation. The steps parallel that of cartoon character Mickey Mouse, who went from having a pointy nose and a head proportional to his body to having an upturned snout, big eyes and a large head. (Bonnett’s theory is that imaginary characters like Mickey help to set the trend for how real animals should look, showing that it’s not just kennel clubs that help to shape our expectations for dogs.)

To recap: The system created to ensure dog purity set dog breeds up for their current problems. “The inbreeding throws up unexpected health problems, which none of the breeders want,” Serpell tells Smithsonian.com. “But it gets very difficult when those health problems are directly related to the conformation of the breed, the standard of the breed.”

Breathing Room

For many dog lovers, behaviors like snoring and snuffling are considered aww-worthy (just check out the many Youtube videos of snoring pugs, reverse sneezing French Bulldogs and congested English bulldogs). But in actuality, they’re often symptoms of a clinical health problem that affects a dog’s everyday quality of life and may require surgical intervention, says Bonnett.

One of the big reasons brachy dogs snuffle is that their soft palate—the flesh on the roof of their mouths—is too long, a vestige of when they had longer snouts. The palate reaches back into their airway, partially blocking it when they breathe. “When the dog pants, extra effort is required to move the soft palate out of the larynx in order to allow air to pass,” writes the Cambridge University Department of Veterinary Medicine. If the dog is breathing through its nose, the extra-long palate creates the same kind of suction as in snoring, sometimes leading to so-called “awake snoring.”

Even sleeping can be painful. Many of these dogs have what’s known as sleep apnea, a condition shared with humans. Because their airway is narrowed, these dogs sometimes need to keep their heads propped up on something in order to sleep without choking.

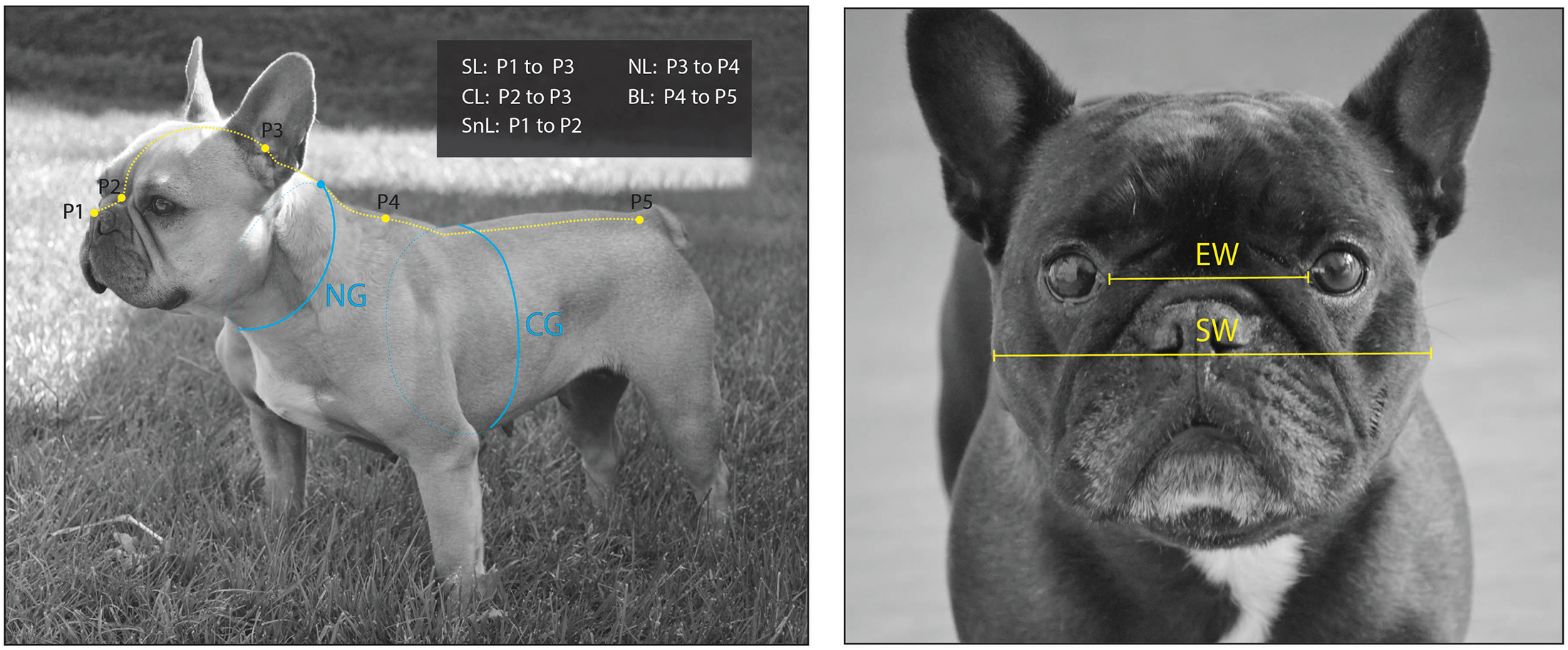

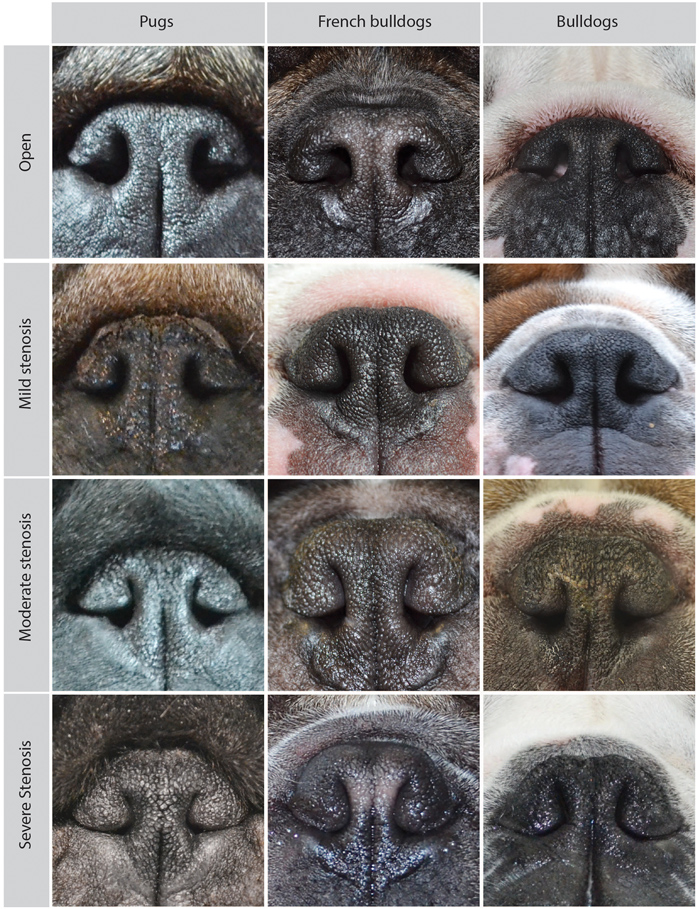

Another factor is nostril shape. In general, brachy dogs have narrowed nostrils, which makes it difficult for them to breathe through their noses and costs them more effort to breath at all, writes Cambridge. It’s also a big part of the reason for French Bulldogs’ characteristic open-mouthed grin. As Bonnett writes, “dogs with BOAS may be short of breath, snore, wheeze, gag, regurgitate and vomit.” Some dogs who suffer from these symptoms need surgery to correct their breathing issues.

Still, even surgery won’t solve the problem entirely. “While many patients have improvement of clinical signs following surgery, almost all animals will continue to exhibit some degree of upper airway obstructive signs,” reads a report from the University of Pennsylvania’s Ryan Veterinary Hospital. In a 2017 study of Danish dog insurance data published in the journal PLOSOne, Serpell and coauthors found that data showed that French Bulldogs have an astonishingly high risk of dying due to respiratory problems: 14-70 times the risk of all breeds.

Yet few owners and even vets recognize that these issues are problematic. In 2012, research from the Royal Veterinary College in Britain found that some owners of brachycephalic dogs perceive even wheezing strong enough to constitute brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome as “normal” for the breed. Vets can often contribute to this perception by calling these behaviors normal, says Bonnett.

“Well, it’s usual for the breed but it’s certainly not normal as a dog,” she says. “You can’t just say to people that it’s normal that your dog can’t breathe or he faints when he runs to the door.” Normalizing dog behaviors that are symptoms of chronic problems, she adds, means that owners may not ever realize their dog is unhealthy.

That’s why, in 2017, the British Veterinary Association launched an awareness campaign dubbed #breedtobreathe. According to a large survey of veterinarians, 75 percent of owners were unaware of the health problems of brachycephalic breeds before they chose their dog. And just 10 percent of owners could identify health problems related to such breeds, with many thinking that problems including snorting were “normal” for such dogs.

Other Health Issues

If there’s one condition that best illustrates the distance between nature and dogs deliberately bred to have extreme conformations, it’s the prevalence of Caesarean sections in brachycephalic breeds. A 2010 study published in the Journal of Small Animal Practice looked at the data from a UK Kennel Club survey of 13,141 female dogs who were pregnant to find that the rate of C-sections among the Boston terriers, bulldogs and French bulldogs was greater than 80 percent. In other words: human intervention was required for the continued propagation of these breeds.

Puppies with extra-big heads—as are common to the brachycephalic breeds—are difficult for mother dogs to birth naturally. Additionally, many brachycephalic breed standards, like that of the French bulldog, call for narrow hips, which makes birthing difficult if not impossible. In the case of English Bulldogs, “Survival of this breed is truly dependent on human intervention,” write the authors of a 2015 study in the journal Canine Genetic Epidemiology. “Because foetus head size of this breed … is too large to pass unaided through the female’s pelvis, up to 94 percent of all births require Caesarean sections to deliver litters.”

Then there’s syringomyelia, a neurological condition that occurs when the dogs’ brains are actually too large for their skulls. A 2010 study published in The Canadian Veterinary Journal found that a whopping 95 percent of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels are at risk of developing the skull-brain size mismatch that can result in syringomyelia, with clinical symptoms of the disease present in about 35 percent of those dogs. Syringomyelia is also a (smaller) risk for small dog breeds including brachycephalic breeds like the Chihuahua, Griffon Bruxellois and Papillion.

Dogs with the condition experience cerebral fluid leaking into their upper spines, creating cysts. This can cause them to drool, exhibit neurological symptoms like not being able to walk properly, and–as was dramatically captured in the documentary Pedigree Dogs Exposed–sometimes scream in agony. These dogs can be treated with seizure medication, with steroids and anti-inflammatories to help bring down swelling and with surgery–but some dogs have to be put down.

A 2014 study of the 240 Cavalier King Charles Spaniels registered with the Danish Kennel Club found that 20 percent of the dogs showing symptomatic syringomyelia were euthanized as a result of the condition.

Spinal issues also threaten the wellbeing of some brachycephalic breeds. Flat-faced dogs often have a vertebral malformation called hemivertebrae, which causes the oddly-shaped vertebrae that causes the curly tail of pugs and French bulldogs. But as the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare notes, if hemivertebrae are present in other parts of the spine it can “lead to instability and deformity of the spinal column.” This condition then leads to the spinal cord or the nerves that rely on it getting squished or damaged, resulting in pain, wobbliness, paralysis and incontinence.

Yet despite the fact that tail conformation is directly linked to these conditions, kennel clubs consider curly tails to be a desirable breed characteristic. The breed standard for pugs listed by the Kennel Club stipulates that the tail should be “curled as tightly as possible over hip, double curl highly desirable.” The American Kennel Club breed standards are similar, adding that “the double curl is perfection.”

…..

If brachy dogs have problems like these—which are lifelong, expensive and cause stress to both pets owners—why are these breeds still so popular? Recent research points to a surprising answer. In 2017, Serpell and study coauthors including ethicist Peter Sandoe surveyed brachy dog owners in Denmark to find an apparent paradox at work. The authors write: “people buy breeds of dog that are predisposed to disease and other welfare problems, while at the same time caring deeply about their dogs.”

Intriguingly, many study participants said they adopted dogs perceived to be unhealthy because they wanted the opportunity to provide caregiving rather than adopting a healthier dog. For both the owners of Chihuahuas and Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, high levels of behavior problems and health issues actually made the owners feel closer to their dogs and more likely to get a dog of that breed again. For the owners of French bulldogs, this was also somewhat true, though those with very sick individual dogs were unlikely to get another French bulldog.

Once, purebred dogs were bred for their speed, strength and athleticism. With brachy breeds, “we still breed these dogs for a function,” Bonnett says. But today “the function is called ‘companion.’” As Rowena Packer of the Royal Veterinary College puts it to The Guardian: These dogs “have been bred to effectively have problems.”

In a culture that celebrates pups that sport adorable faces but can barely fend for themselves, the fact that many of our pets are burdened by breed-related conditions raises the question: can the damage we’ve done been undone?