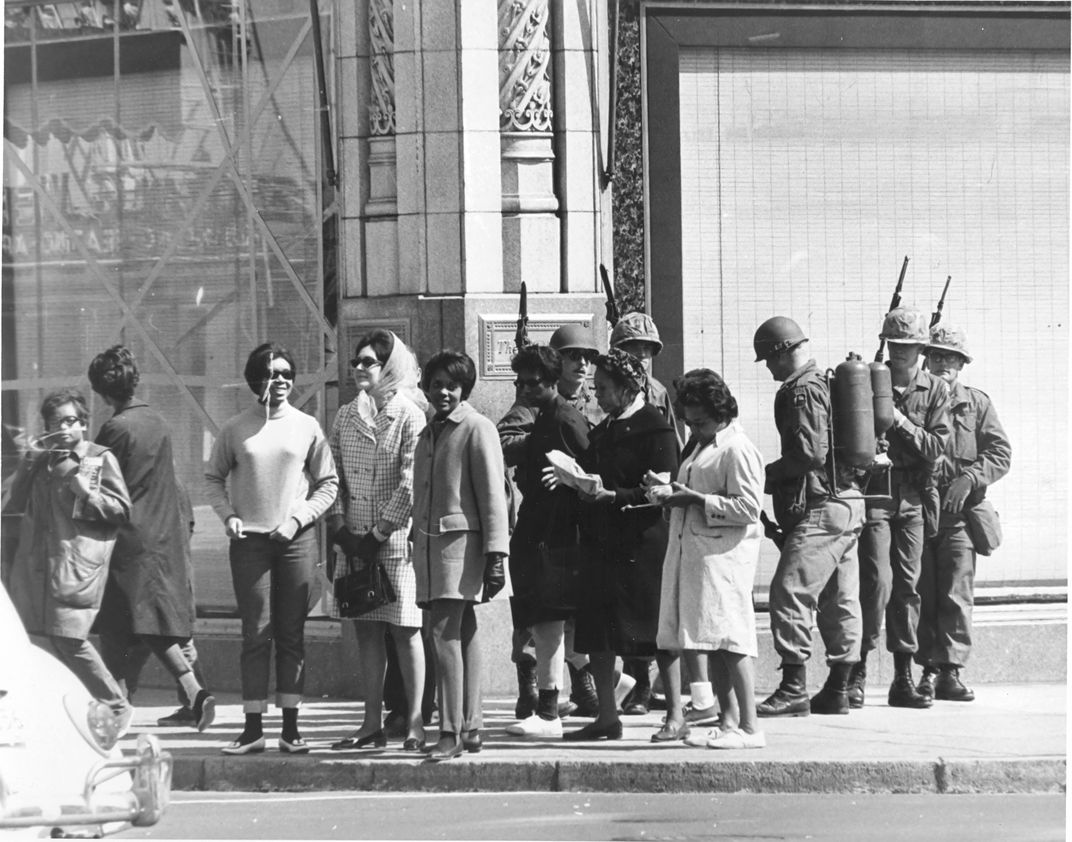

It’s a cool April’s Day in Washington, D.C. The year is 1968. A group of women are huddled on a street corner, the majority African-American. Behind them, one can make out a shuttered storefront—that of Hecht’s department store, vandalized in the days prior by rioters enflamed by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Alongside the women—some agitated, others at ease—stand five national guardsmen, looking like soldiers plucked from Vietnam with their long rifles, black boots and bulky helmets.

Not pictured in the arresting photo, taken on F Street, is a quietly majestic nearby edifice, left unscathed by looters and on the verge of its grand reopening to the public. That building, dedicated in 1836 by Andrew Jackson, had long served as a patent office. Over the years, however, it had fallen into a state of disrepair.

Now, amidst all the grief and fury of 1968, it was to be reopened as a beacon of across-the-board American achievement—a signifier of hope in a desperate time. The National Collection of Fine Art (a precursor to today’s Smithsonian American Art Musuem) would now occupy one half of the structure, and would begin admitting visitors that May. A new museum, the National Portrait Gallery, would occupy the other half, and would open in October.

This fraught origin story lies at the heart of the National Portrait Gallery’s new exhibition, “Celebrating 50 Years,” marking the anniversaries of both Smithsonian museums.

Housed in what was once the vestibule of the old patent office building, the exhibition showcases a wide assortment of photographs, ephemera and other artifacts dating back to the museums’ 1968 debut. The significance of the black-and-white image of those women and guardsmen sharing a street corner is not lost on National Portrait Gallery historian James Barber, the exhibition’s curator.

“This was not a happy time for Washington,” Barber says. “But museums were scheduled to open.” If anything, the widespread disillusionment over the death of Martin Luther King and the drawn-out conflict in Vietnam only confirmed the urgent need for the new twin museums, which would highlight aspects of America worth celebrating. Barber recalls that the “President said that the Smithsonian was the one bright spot in the area at this time.”

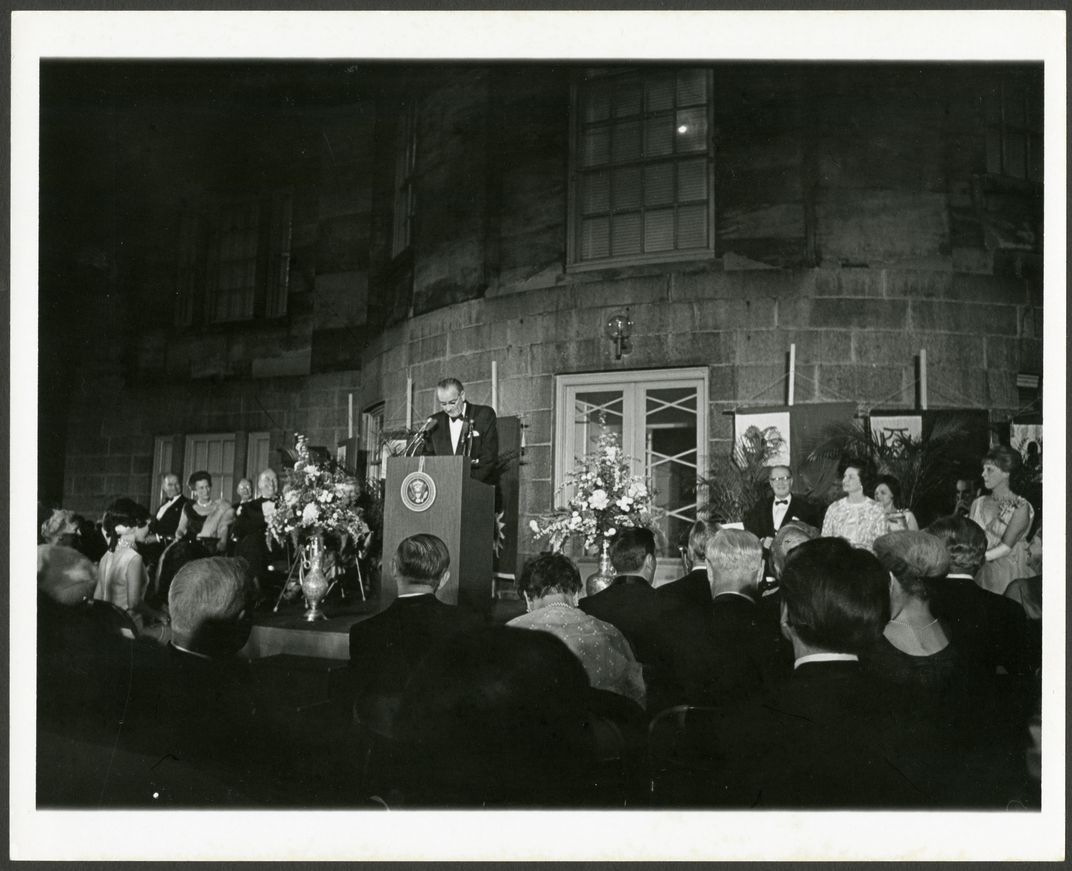

The beleaguered Lyndon Baines Johnson had just delivered a bombshell public speech in which he both disavowed the goal of victory in Vietnam and declared that he would not be seeking a second term. Yet, Johnson graciously oversaw the May unveiling of the National Collection of Fine Art. A pair of photographs depict Johnson and his wife Ladybird contemplating the artworks hung from the refurbished walls.

The President was no doubt cheered by what he saw: the NCFA collection, which was created in 1906, now had a beautiful, historic home. Under the stewardship of director David Scott, who broadened the scope of the collections, the museum came to include contemporary and modern art as well as classical works.

The principal artistic backdrop for the May opening was a series of six colorful and thematically disparate posters commissioned specially for the occasion. “Celebrating 50 Years” presents visitors with three of the six, one of them by famed New York-born artist Larry Rivers. Prior to the opening, the series had been displayed in the windows of Garfinckel’s department store, a Washington, D.C. shopping mainstay, as a lure for passersby.

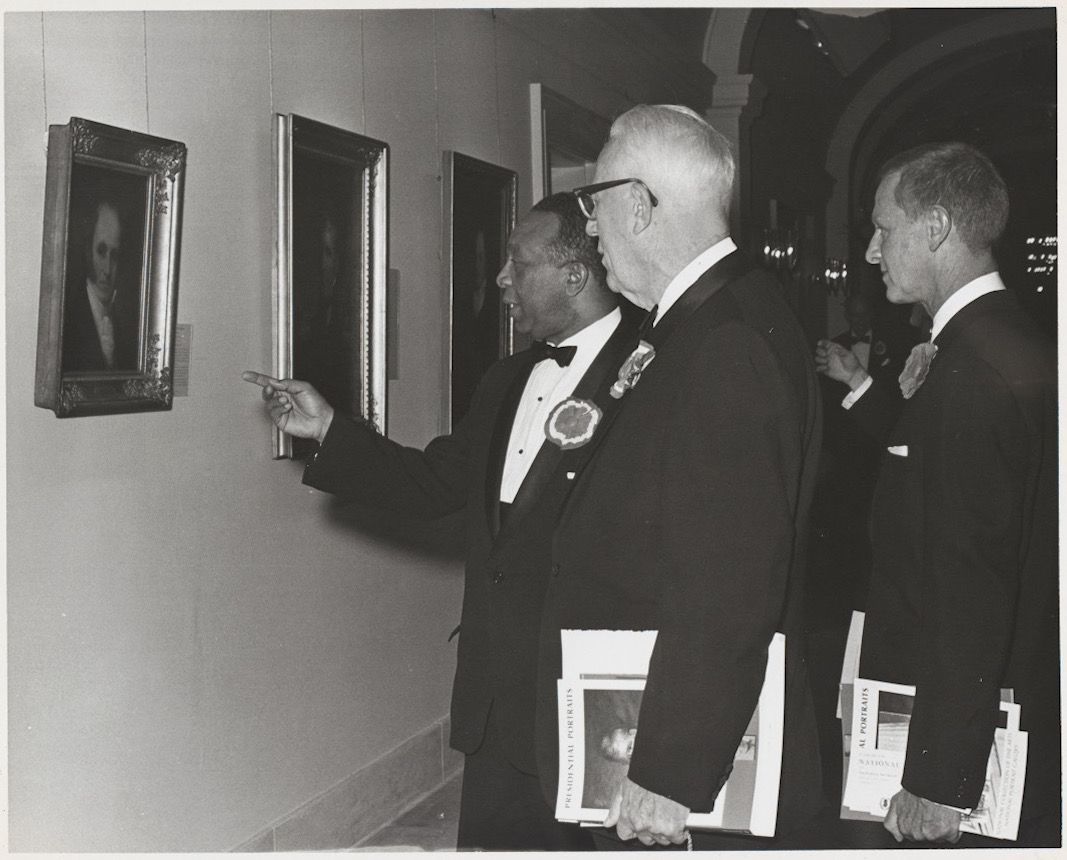

The Portrait Gallery’s debut later in October was also met with lively fanfare. It featured a symposium, and guests on hand for day one of the museum’s first show (entitled “The American—This New Man”) included future Librarian of Congress Daniel J. Boorstin, historian Marcus Cunliffe, and renowned anthropologist Margaret Mead.

The National Portrait Gallery was new. Founded just six years earlier, its inventory would have to be amassed from the ground up. Given this blank slate, striking the right tone from the outset was key.

In the inaugural catalog—on view in the exhibition—its first director, Charles Nagel, laid out his philosophical vision for the space, arguing that the National Portrait Gallery should not, at its heart, be a portrait museum, but rather an American museum. To him, the stories of those depicted were more important than the techniques used to depict them. Art would be the vehicle, but knowledge and understanding of America’s heritage would be the substance.

“The portrait gallery is a museum of history and biography that uses art as a medium,” curator Barber says. “And it could be many mediums. For the most part, it’s the fine arts—painting and sculpture—but it could be photography, theater arts, drama. . .”

The museum’s emphasis on knowledge and history is ultimately what drew community support to it. Initially, there was some worry that the fledgling 1968 collection—featuring a very high percentage of loaned pieces—would be able to get off the ground and establish itself in its own right. Such fears soon proved ill-founded: countless people were willing and able to contribute to the mission of the new museum.

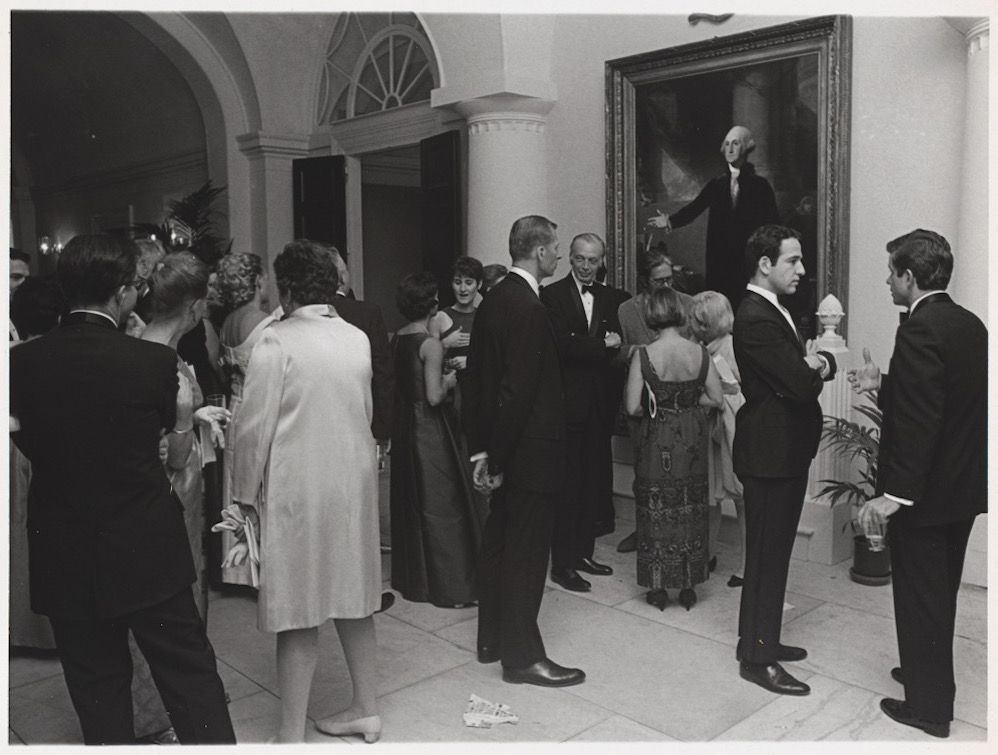

Most notably, perhaps, is the case of the National Portrait Gallery’s iconic Lansdowne portrait of George Washington, painted by Gilbert Stuart in 1796. Displayed at the 1968 opening ceremony, Washington looked out over the crowd, hand magnanimously outstretched—but the portrait was not yet owned by the museum. The owner of the painting, a native of the United Kingdom, had generously lent it to the Smithsonian, where it remained in place for 30 years. In 2000, the owner decided to sell the Landsdowne. His asking price: $20 million.

Where exactly this funding would come from was initially unclear. But when museum director Marc Pachter appeared on the “Today Show” one morning and pithily stressed the historical import of the painting, the money appeared instantaneously. Fred W. Smith, the president of the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, an organization traditionally focused on projects involving buildings and medical research, happened to be tuned in, and decided that this was to be his organization’s next major investment.

Single-handedly footing the $20-million bill, the Reynolds Foundation donated $10 million in additional funds to cover the cost of taking the Lansdowne on a crosscountry road trip while the museum was being upgraded. Evidently, the portrait gallery’s mission had resonated.

“That distinction”—between art for art’s sake and art for the people’s sake—“is so critical to what we do,” says Barber.

Walking among the ephemera gathered for the 50th anniversary exhibition, the curator’s attention is drawn to a modest gallery brochure—one of the very first to be printed. Depicted on its front is a portrait of Pocahontas, one of the oldest works in the collections. Reflecting on the story contained in this image, and those to be found within all the other varied materials in the collection, he can’t help but be moved.

Barber finds mirrored in the Portrait Gallery’s works the overwhelming, awe-inspiring diversity of American life. “Not just presidents,” he says, “but engineers, scientists, people in medicine, poets, artists, innovators. . .” all are celebrated here.

Now, just as during the tumult of the late 1960s, the old patent office building stands as a place of refuge and warmth, where Americans of all stripes can find themselves in their nation’s history.

“That’s what this catalog is about,” Barber tells me: “the wide variety of people that helped build this country, make this country what it is.”

“Celebrating 50 Years” is on view through January 6, 2019 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.