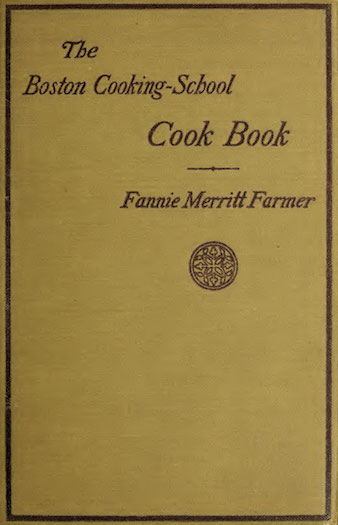

The first edition of the Boston Cooking-School Cook Book—now known as TheFannie Farmer Cookbook—reads like a road map for 20th-century American cuisine. Published in 1896, it was filled with recipes for such familiar 19th-century dishes as Potted Pigeons, Creamed Vegetables, and Mock Turtle Soup. But it added a forward-looking bent to older kitchen wisdom, casting ingredients such as cheese, chocolate, and ground beef—all bit players in 19th-century U.S. kitchens—in starring roles. It introduced cooks to recipes like Hamburg Steaks and French Fried Potatoes, early prototypes of hamburgers and fries, and Fruit Sandwiches, peanuts sprinkled on fig paste that were a clear precursor to peanut butter and jelly.

Americans went nuts for the 567-page volume, buying TheBoston Cooking-School Cook Book in numbers the publishing industry had never seen—around 360,000 copies by the time author Fannie Farmer died in 1915. Home cooks in the United States loved the tastiness and inventiveness of Farmer’s recipes. They also appreciated her methodical approach to cooking, which spoke to the unique conditions they faced. Farmer’s recipes were gratifyingly precise, and unprecedentedly replicable, perfect for Americans with newfangled gadgets like standardized cup and spoon measures, who worked in relative isolation from the friends and family who had passed along cooking knowledge in generations past. Farmer’s book popularized the modern recipe format, and it was a fitting guide to food and home life in a modernizing country.

Recipes today serve many purposes, from documenting cooking techniques, to showing off a creator’s skills, to serving up leisure reading for the food-obsessed. But their most important goal is replicability. A good recipe imparts enough information to let a cook reproduce a dish, in more or less the same form, in the future.

The earliest surviving recipes, which give instructions for a series of meaty stews, are inscribed on cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia. Recipes also survive from ancient Egypt, Greece, China, and Persia. For millennia, however, most people weren’t literate and never wrote down cooking instructions. New cooks picked up knowledge by watching more experienced friends and family at work, in the kitchen or around the fire, through looking, listening, and tasting.

Recipes, as a format and genre, only really began coming of age in the 18th century, as widespread literacy emerged. This was around the same time, of course, that the United States came into its own as a country. The first American cookbook, American Cookery, was published in 1796. Author Amelia Simmons copied some of her text from an English cookbook but also wrote sections that were wholly new, using native North American ingredients like “pompkins,” “cramberries,” and “Indian corn.” Simmons’s audience was mainly middle-class and elite women, who were more likely to be able to read and who could afford luxuries like a printed book in the first place.

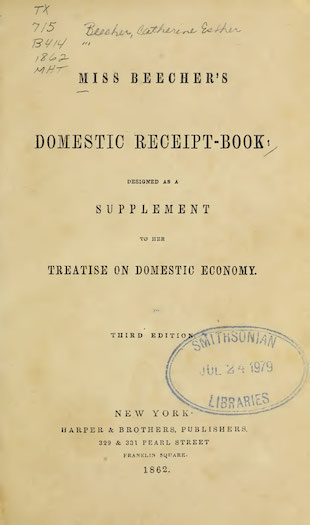

The reach of both handwritten recipes and cookbooks would expand steadily in the coming decades, and rising literacy was only one reason. Nineteenth-century Americans were prodigiously mobile. Some had emigrated from other countries, some relocated from farms to cities, and others moved from settled urban areas to the Western frontier. Young Americans regularly found themselves living far from friends and relatives who otherwise might have offered help with cooking questions. In response, mid-19th-century cookbooks attempted to offer comprehensive household advice, giving instructions not just on cooking but on everything from patching old clothes to caring for the sick to disciplining children. American authors routinely styled their cookbooks as “friends” or “teachers”—that is, as companions that could provide advice and instruction to struggling cooks in the most isolated of spots.

Americans’ mobility also demonstrated how easily a dish—or even a cuisine—could be lost if recipes weren’t written down. The upheaval wrought by the Civil War singlehandedly tore a hole in one of the most important bodies of unwritten American culinary knowledge: prewar plantation cookery. After the war, millions of formerly enslaved people fled the households where they had been compelled to live, taking their expertise with them. Upper-class Southern whites often had no idea how to light a stove, much less how to produce the dozens of complicated dishes they had enjoyed eating, and the same people who had worked to keep enslaved people illiterate now rued the dearth of written recipes. For decades after the war, there was a boom in cookbooks, often written by white women, attempting to approximate antebellum recipes.

Standardization of weights and measures, driven by industrial innovation, also fueled the rise of the modern American recipe. For most of the 19th century, recipes usually consisted of only a few sentences giving approximate ingredients and explaining basic procedure, with little in the way of an ingredient list and with nothing resembling precise guidance on quantities, heat, or timing. The reason for such imprecision was simple: There were no thermometers on ovens, few timepieces in American homes, and scant tools available to ordinary people to tell exactly how much of an ingredient they were adding.

Recipe writers in the mid-19th century struggled to express ingredient quantity, pointing to familiar objects to estimate how much of a certain item a dish needed. One common approximation, for instance, was “the weight of six eggs in sugar.” They also struggled to give instructions on temperature, sometimes advising readers to gauge an oven’s heat by putting a hand inside and counting the seconds they could stand to hold it there. Sometimes they hardly gave instructions at all. A typically vague recipe from 1864 for “Rusks,” a dried bread, read in its entirety: “One pound of flour, small piece of butter big as an egg, one egg, quarter pound white sugar, gill of milk, two great spoonfuls of yeast.”

By the very end of the 19th century, American home economics reformers, inspired by figures like Catharine Beecher, had begun arguing that housekeeping in general, and cooking in particular, should be more methodical and scientific, and they embraced motion studies and standardization measures that were redefining industrial production in this era. And that was where Fannie Merritt Farmer, who started working on The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book in the 1890s, entered the picture.

Farmer was an unlikely candidate to transform American cookery. As a teenager in Boston in the 1870s, she suffered a sudden attack of paralysis in her legs, and she was 30 years old before she regained enough mobility to begin taking classes at the nearby Boston Cooking School. Always a lover of food, Farmer proved to be an indomitable student with a knack for sharing knowledge with others. The school hired her as a teacher after she graduated. Within a few years, by the early 1890s, she was its principal.

Farmer started tinkering with a book published by her predecessor a few years earlier, Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cook Book. Farmer had come to believe that rigorous precision made cooking more satisfying and food more delicious, and her tinkering soon turned into wholesale revision.

She called for home cooks to obtain standardized teaspoons, tablespoons, and cups, and her recipes called for ultra-precise ingredient amounts such as seven-eighths of a teaspoon of salt, and four and two-thirds cups of flour. Also, crucially, Farmer insisted that all quantities be measured level across the top of the cup or spoon, not rounded in a changeable dome, as American cooks had done for generations.

This attention to detail, advocated by home economists and given life by Farmer’s enthusiasm, made American recipes more precise and reliable than they ever had been, and the wild popularity of Farmer’s book showed how eager home cooks were for such guidance. By the start of the 20th century, instead of offering a few prosy sentences that gestured vaguely toward ingredient amounts, American recipes increasingly began with a list of ingredients in precise, numerical quantities: teaspoons, ounces, cups.

In more than a century since, it’s a format that has hardly changed. American cooks today might be reading recipes online and trying out metric scales, but the American recipe format itself remains extraordinarily durable. Designed as a teaching tool for a mobile society, the modern recipe is grounded in principles of clarity, precision, and replicability that emerge clearly from the conditions of early American life. They are principles that continue to guide and empower cooks in America and around the world today.

Helen Zoe Veit is an associate professor of history at Michigan State University. She is the author of Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating and the editor of Food in the American Gilded Age. She directs the What America Ate website. She wrote this for What It Means to Be an American, a project of the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square.