On page and on screen, few settings carry the cultural weight of the humble American diner. Inviting us in with slick chrome and blinking neon, the diner is coolly seductive. It appeals to our baser impulses with outsized portions of high-cholesterol breakfast and pie, wins us over with chatty waitresses and classic jukebox jams, and reminds us, in a fundamental yet inscrutable way, that America itself isn’t always what it seems.

A diner is where Pumpkin and Honey Bunny make their move in Pulp Fiction; where Tony sits down for his final meal on The Sopranos; where the adrift young men of American Graffiti gather to discuss their futures; where Danny and Sandy’s date gets crashed in Grease. Diners suffuse the writings of hard-boiled authors like Jack Kerouac and James Ellroy. In “Twin Peaks,” the otherworldly Washington State locale dreamed up by David Lynch, the Double R is a community mainstay.

Actress Lara Flynn Boyle, who portrayed “Twin Peaks”’ Donna Hayward in the 1990s, says she once waited tables herself at the venerable Ann Sather restaurant in her native Chicago (the cinnamon rolls are legendary). More than anything, Boyle adores the casual camaraderie of a countertop meal. “There’s nothing like it! It’s a dying art form,” she says, a hint of wistfulness in her voice. “It’s just so lovely. People actually talk to each other.” Half the fun, in Boyle’s view, is striking up off-the-wall dialogues with strangers—an increasingly rare activity in the smartphone era. “You meet the most delicious people,” she says, “and it’s just fantastic. Diners are my life.”

What is it about cheap eats, long hours, counters, and booths that so consistently captures the American imagination? Putting a finger on it is no mean feat, but unpacking the history crammed tight within diners’ walls seems like a fine place to start.

The name “diner” first referred to railway cars in which riders chowed down (compare “sleepers”). Later, it was applied to rough-and-tumble eateries that catered to factory hands in late-1800s industrial America. In many cases, these establishments were, in fact, retrofitted boxcars, placed outside blue-collar workplaces to provide sustenance to the late-night crowds, with little emphasis on nutrition or decorum.

Food critic and diner buff Michael Stern, co-author (with his wife Jane) of the Roadfood book series, recounts the transformation diners underwent in the Roaring Twenties, when young, fashionable women were out on the town in force, looking for a good time and unafraid to drain their pocketbooks.

“That was when many diners were spiffing up,” Stern says, “and trying to welcome ladies. They had indoor bathrooms, and booths, so you didn’t have to sit at a counter.” This meant that the womenfolk wouldn’t have to rub elbows with stinky and suspicious males, and that diners would henceforth be viable date night locations (Danny and Sandy’s misadventure notwithstanding).

Many such diners were mass-produced in factories in East Coast hubs, each one a cookie-cutter copy of every other. They all had the same silvery exterior, the same counter, the same open kitchen, the same cramped quarters. From their plants, the diners were driven across the nation, their oblong, RV-like structure lending them to transport via flatbed trucks. In the case of larger diners, the buildings were often conveyed to their destinations in two separate pieces, and reassembled on site.

Despite the rebranding campaign, Stern notes that early films depicting diners remained fixated on the idea of the diner as a dangerous, unpredictable place, where louche characters mingled and violence was liable to erupt.

In the Preston Sturges odyssey movie Sullivan’s Travels, released in 1941, a Hollywood director goes out of his way to mingle with the lowly citizens assembled in a town diner. In Stern’s view, such an excursion was—and in some cases, still is—thought to constitute “a walk on the wild side of culture.” Sturges’s protagonist was “slumming it”—perhaps risking personal injury in the process.

Richard Gutman, avid diner historian and former director of the Culinary Arts Museum at Johnson & Wales University, agrees with this assessment. “Certain people didn’t go into diners,” he says, “because they were these places that somehow attracted a ‘lesser clientele.’”

After the Second World War, diners kicked their respectability efforts into overdrive. Gutman recalls a Saturday Evening Post piece, published on June 19, 1948, with the punning headline, “The Diner Puts on Airs.” “It basically talked about all the fabulous new air-conditioned gigantic diners, where you could get lobster, everything,” Gutman says. Finally, the diner was a truly across-the-board destination. “Everybody wants to go.”

Even so, the appeal of classic no-frills diners never quite wore off—and neither did the darker side of their reputation. Modern-day gangster films remain likely to feature diner scenes, and Jack Kerouac’s meticulous descriptions of the stench of dishwater and counters pocked with knife marks are, in Michael Stern’s mind, immortal.

With this said, the anomie and unpredictability we sometimes associate with diners derives, at heart, from their democratic nature; the only reason we suppose anything can happen in a diner is that everyone is welcome there. What makes diners strange and unnerving from one point of view is exactly what renders them warm and homey from another: the eclectic blend of the people who eat there, and their willingness to approach you on a whim.

This openness to idle chatter frequently extends to waitstaff. “I really think a diner is a place where, if you want to buy into it, you can become a favorite customer practically the first time you’re there,” Gutman says, “by engaging the people behind the counter, by having a conversation with them, by speaking up, by making a joke. And they will, generally speaking, respond in kind.”

Gutman fondly recalls a recent occasion on which he and his daughter visited a diner that had served as a childhood haunt of hers. “When we pulled up,” he says, “they literally put her grilled cheese sandwich on the grill,” no questions asked. Gutman’s daughter is 33 years old now, and she had her young son in tow. But for old times’ sake, the cooks whipped up “exactly what she had when she was five!”

Boyle, the “Twin Peaks” actress, points out that, in their acceptance of lone visitors, diners are not dissimilar to town parishes. In most restaurants, she says, going stag means that “people are looking at you, and you’re like, ‘Oh my god, they either feel sorry for me or I’m a weirdo.’” Not so with diners. In a diner, she says, “I’m all good. I don’t have to pretend like I’m reading a paper. I don’t have to pretend like I’m on my phone. I can just sit there. And if I look like a loser? Fine, whatever. I don’t care.”

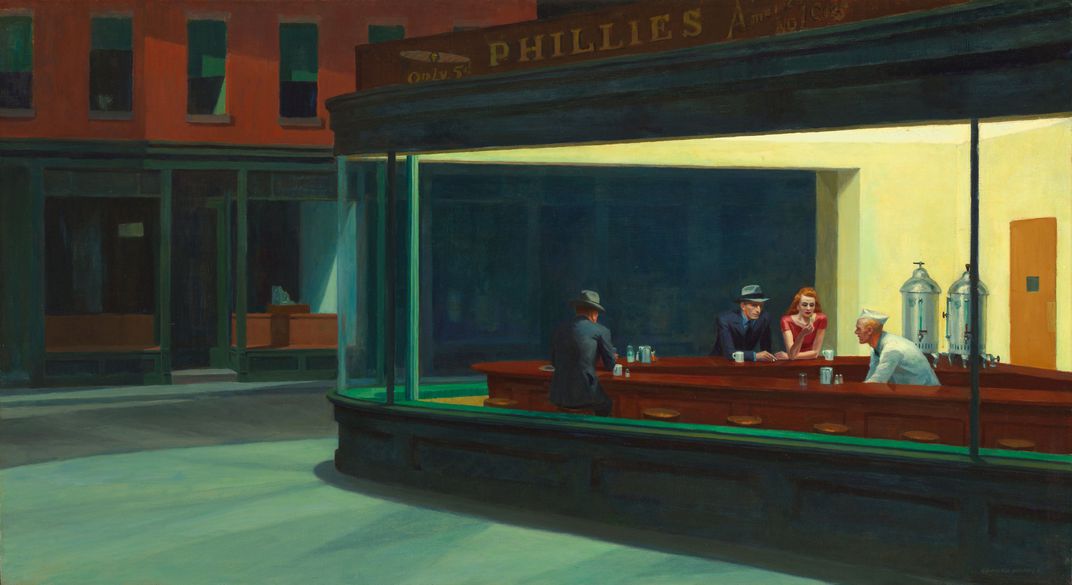

Where Michael Stern sees in Edward Hopper’s classic diner tableau Nighthawks an isolating and fearful place, Boyle sees just the opposite—an opportunity to enjoy a meal free from judgment, and the delightful possibility of unexpected conversation. Cold and solitary from one vantage, warm and convivial from another—it is this duality, bolstered by the American democratic ideal, that explains diners’ evergreen intrigue.

In Boyle’s view, it was the home-away-from-home side of diners that David Lynch so successfully brought to bear when he created the larger-than-life Double R. On “Twin Peaks,” the bereaved of the town mass at the diner in the wake of Laura Palmer’s death, seeking answers, swapping words, and ordering ample comfort food.

“What David tapped into is, as much as you’re different, you go into the coffee shop, you sit at the counter, you’re all the same person. And then, once you walk out the door, who knows what’s going to happen?” For Lynch, the Double R serves as a place of refuge from the town’s churning darkness, a benevolent sanctuary where differences are smoothed over.

“It was just a wonderful place to try to find some solace and some warmth,” Boyle says. “And that’s really what diners are all about.”