When Léna Roy was 7 years old, her teacher read the first chapter of A Wrinkle in Time aloud to her second-grade class. After school, Léna ran to her grandmother’s house, which was around the corner from her school on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, to finish the book on her own. She curled up in bed and devoured it. She felt just like the hotheaded, stubborn heroine Meg Murry, and took comfort in the fact that a flawed adolescent girl could save the world. “It was almost like your permission to be a real person,” Roy says. “You don’t have to be perfect.”

Millions of other adolescent girls (and boys) have made the same liberating discovery while reading A Wrinkle in Time. What’s different about Roy is that her grandmother happened to be Madeleine L’Engle, the book’s author, who revolutionized serious young adult fiction with her clever mash-up of big ideas, science fantasy and adventure—and a geeky girl action hero way ahead of her time.

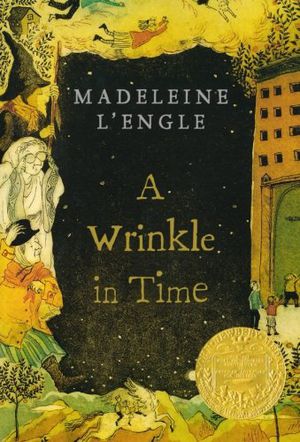

Since its 1962 publication, Wrinkle has sold more than ten million copies and been turned into a graphic novel, an opera and two films, including an ambitious adaptation from the director Ava DuVernay due out in March. The book also kicked open the door for other bright young heroines and the amazingly lucrative franchises they appear in, from whip-smart Hermione Granger in the Harry Potter books to lethal Katniss Everdeen in the Hunger Games. Leonard Marcus, author of the L’Engle biography Listening for Madeleine, says Wrinkle “set the stage for the reception of Harry Potter in this country.” Previously, he says, science fiction and fantasy were suitable for high-end British authors like C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien in Britain but in the States were relegated to pulp magazines and drugstore paperbacks.

Then came L’Engle, a 41-year-old writer who spent three months in 1959 writing the hard-to-categorize story that would become A Wrinkle in Time. While Meg Murry and her companions traveled through time and space to save her father, a scientist trapped by evil forces on a distant planet, readers had to wrap their minds around the fifth dimension, the horrors of conformity and the power of love. L’Engle believed that literature should show youngsters they were capable of taking on the forces of evil in the universe, not just the everyday pains of growing up. “If it’s not good enough for adults,” she once wrote, “it’s not good enough for children.”

Publishers hated it. Every firm her agent turned to rejected the manuscript. One advised to “do a cutting job on it—by half.” Another complained “it’s something between an adult and juvenile novel.” Finally, a friend advised L’Engle to send it to one of the most prestigious houses of all, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. John Farrar liked the manuscript. A test reader he gave it to, though, was unimpressed: “I think this is the worst book I have ever read, it reminds me of TheWizard of Oz.” Yet FSG acquired it, and Hal Vursell, the book’s editor, talked it up in letters he sent to reviewers: “It’s distinctly odd, extremely well written,” he wrote to one, “and is going to make greater intellectual and emotional demands on 12 to 16 year olds than most formula fiction for this age group.”

When it debuted, not only was Wrinkle widely praised—“wholly absorbing,” said the New York Times Book Review—but it won the Newbery Medal, the most important award in children’s lit. “The almost universal reaction of children to this year’s winning book, by wanting to talk about it to each other and to elders, shows the deep desire to understand as well as to enjoy,” said Newbery committee member Ruth Gagliardo. American publishers, initially resistant to genre bending, soon were producing their own teen epics, including Lloyd Alexander’s Newbery-winning Chronicles of Prydain books and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea series.

L’Engle went on to write more than 40 books, including works of nonfiction and poetry, though none was as acclaimed as Wrinkle. None was as controversial, either. Libraries and schools frequently banned the novel because of its entanglements with religion. In one passage, Jesus Christ is compared to Shakespeare, Einstein and the Buddha—a heretical notion to some authorities. On the American Library Association’s list of most “frequently challenged” for the 1990s, Wrinkle was No. 23.

Among the countless girls changed forever by L’Engle’s book was Diane Duane, who first read it as a 10-year-old in 1962. She’d consumed all the science fiction and fantasy at her local library but had never encountered anyone like Meg. “Finally,” Duane recalls, “here was a girl character being treated as if her take on what was going on around her, her analysis and her emotional reactions to the things that were happening around her, were real and were worth paying attention to.” Today Duane is hailed as the best-selling author of So You Want to Be a Wizard and other titles in her Young Wizards fantasy series, which features a young female protagonist, Nita. “All the time L’Engle’s shadow—and a very bright shadow, it has to be said—was lying over that work for me,” she says. “It would have been very difficult for me to do that writing without thinking about her a lot.”

Léna Roy, who is a writing teacher in New York and the co-author of an upcoming biography of her grandmother, Becoming Madeleine, doesn’t remember L’Engle ever calling herself a feminist, though she was proud of being what Roy calls a “trailblazing woman.” L’Engle had spent her years at Smith College editing the campus literary magazine alongside Betty Friedan, who later penned The Feminine Mystique. L’Engle herself suggested it was easy to make her protagonist a strong girl. “I’m a female,” she once said. “Why would I give all the best ideas to a male?”

Now the movie adaptation of Wrinkle is poised to make L’Engle’s creation even more groundbreaking. DuVernay, the first woman of color to direct a live-action film with a production budget over $100 million, intentionally cast nonwhite actors in lead roles. (Storm Reid will play Meg, and Deric McCabe will play her younger brother Charles.) In 1962, it was radical to see a young girl in charge. Now a new generation of black girls (and boys) can see themselves onscreen and dream of saving the world.

A Wrinkle in Time (Time Quintet)

It was a dark and stormy night; Meg Murry, her small brother Charles Wallace, and her mother had come down to the kitchen for a midnight snack when they were upset by the arrival of a most disturbing stranger.

Rebels With a Cause

The bravest and brainiest girls in literature have been breaking the rules for 150 years.

Jo March

Little Women (1868): Tomboyish Jo refuses to let household duties get in the way of what she loves most—writing.

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $12

This article is a selection from the January/February issue of Smithsonian magazine