The story of the infant Hercules derived from Greek and Roman mythology, has long been associated with the idea of fighting malice and corruption. The love-child of the god Zeus and the mortal Queen Alcmena, Hercules was repeatedly targeted for death by his jealous stepmother Hera. Demonstrating his considerable strength at an early age, the baby demigod strangled two serpents that Hera had placed in his cradle.

Since ancient times, the story of the infant Hercules has represented the weak overcoming the strong; it was a particularly symbolic metaphor in America—a young nation fighting for independence from powerful Britain.

Not long ago, on a tour of Great Britain’s Spencer House (the ancestral town house of Diana, née Spencer, Princess of Wales), I came across a sculpture combining the weirdest mix of classical imagery and political satire that I’ve ever seen. I think it’s fair to say that I’ve become slightly obsessed with what possibly could be the ugliest sculpture in London.

What follows is a herculean trail through the annals of art history that leads from ancient Greece and Rome, to 18th century Britain, to the American Civil War and ends at the doorstep of President Theodore Roosevelt.

Made of refined marble and about 28 inches in diameter, the Spencer House sculpture is dominated by a baby with the head of a man strangling two snakes. The snakes also have human heads, and the baby-man has been so effective in his defense that he’s managed to sever the head of the one on his right.

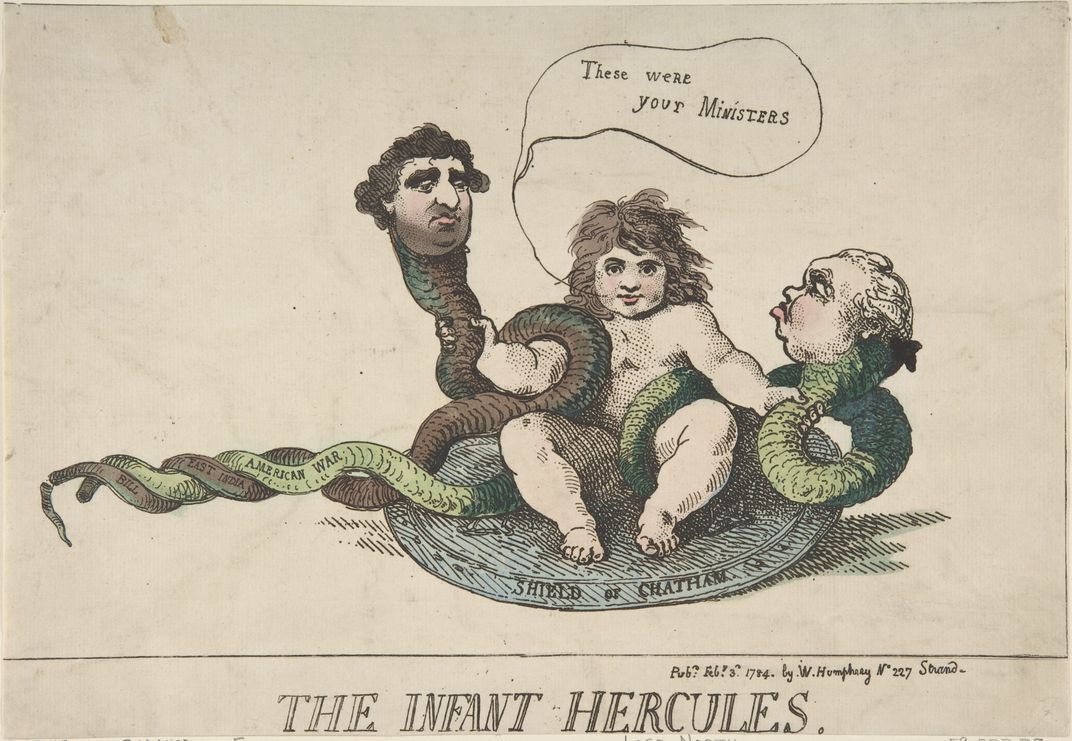

The composition was based on a satirical cartoon titled The Infant Hercules, by Thomas Rowlandson and published on February 3, 1784. The child is identified as William Pitt the Younger because he is perched on the “Shield of Chatham” the name of his ancestral seat. Inscribed on the bodies of the intertwined snakes are the words “American War,”and “East India Bill,” alluding to Pitt’s political rivals Charles James Fox and Lord North whose coalition government had lost America for the King. Produced on the day following Pitt’s successful election to office in 1784, the baby Pitt looks directly at the viewer and say with some measure of chagrin: “These were your MINISTERS.”

In 1783 William Pitt, second son to the Earl of Chatham, became the youngest prime minister of Great Britain at the tender age of 24. Appointed by King George III, Pitt initially faced such a vicious opposition that only the threat of the King’s abdication forced Parliament to accept the choice of his young protégé. Eventually over time however, much of the British peerage grew to admire Pitt as he eliminated the national debt—grown ponderously large after fighting the American colonists—and advanced the power and size of the British Empire by curtailing the growth of the East India Company.

One of Pitt’s admirers was Frederick Augustus Hervey the Fourth Earl of Bristol, who around 1790 commissioned the relatively unknown Italian sculptor Pierantoni (called “Sposino”), to create the Spencer House sculpture. What makes the object so remarkable—and ugly—is that Hervey turned a satirical cartoon into a form of high art that is more traditionally reserved for ennobling portraits and morally uplifting stories generally from mythology, the Bible, or classical literature.

And without surprise, as the sculpture was shown publicly, audiences were shocked and appalled.

A discerning Lady Elizabeth Webster wrote in her journal after visiting Sposini’s studio: “..the sculptor [is] a man who has made a lasting monument of Lord Bristol’s bad taste. . .”

Moreover because “the English artists all to a man refused to execute this puerile conceit,” reported Lady Webster, Bristol had to inveigle a copy-artist of classical sculpture based in Italy to do the work.

First-hand accounts of the cheeky and no doubt expensive commission posit that the Earl may have gotten his idea for a marble sculpture by coming across the portrait of Emperor Caracalla as the infant Hercules strangling serpents from 193-200 AD at the Capitoline Museum in Rome on one of his many trips to Europe. Another source of inspiration may have been the painting of The Infant Hercules Strangling Serpents in his Cradle by the British artist Sir Joshua Reynolds on commission for Catherine II of Russia and exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1788.

But allusion of the infant America struggling to free him/herself from British patriarchy was probably already well known by the Earl of Bristol through various forms of popular culture circulating within Europe at the time.

In 1782 for example, the Frenchman A.E. Gibelin represented France as the goddess Minerva, who is depicted protecting the infant Hercules from an attacking Lion, symbolic of Britain. Hercules battles the snakes “Saratoga”and Yorktown,” referring to the American military victories that convinced the French government to formally recognize their cause.

Interestingly, the infant Hercules as “Young America” becomes a term used in the 1840s and 1850s to point to the challenges the new nation was having appeasing factions within its own country. In a Harper’s Weekly cartoon dated September 1, 1860 we see that the French parent Minerva has given way to Columbia, mother of the Republic, who watches over her infant seated on the ballot box struggling with the snakes of disunion and secession on the eve of the Civil War: “Well done, Sonny!,”she says, “Go at it while you are still young, for when you are old you can’t.”

Four years later an engraving by William Sartain of Philadelphia shows that Minerva nee-Columbia is now the American bald eagle watching over Young America seated on a bear rug (symbolizing Britain) crushing the snakes of Rebellion and Sedition. In this context, the infant Hercules embodies the idea of the Union who is trying to stop the dissolution of the United States. The snakes may also reference the contentious “copperhead” democrats who opposed the idea of civil war and wanted an immediate peace settlement with the Confederacy.

Finally, in 1906—closely echoing the Spencer House sculpture with human-headed snakes—a satirical cartoon by Frank A. Nankivell for Puck Magazine captioned “The infant Hercules and the Standard Oil Serpents,” depicts President Theodore Roosevelt as the demigod fighting the serpents John D. Rockefeller, the founder of Standard Oil, and Senator Nelson W. Aldrich, the powerful chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. Aldrich was often the targeted in the satirical press for favoring the interests of big business over social reform, and his head placed on all manner of creatures from spiders, to giant octopus and serpents to signify that his influence was far reaching, controlling and not to the trusted.

This obsession with an ugly sculpture from the 18th century, found by happenstance in London, had led me to early 20th century American politics and banking reform with stops along the way in ancient Greek and Roman mythology, the British peerage and Parliament, France and the American Revolutionary and Civil Wars. Such is the nature of art history; crossing continents, touching multiple disciplines, wending its threads through the course of human events. To quote Beverly Sills “Art is the signature of civilizations.”

As for the ugly Bristol sculpture, how did it end up at Spencer house? It was bought at auction in 1990 as an example of 18th century English folly.