For 150 years, a massive building and its annexes loomed over the East River and Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood. Inside its humid and sticky walls, workers spent long days laboring over machines refining raw sugar from Caribbean plantations. But in 2004, the machines stopped and workers laid off. For the next decade, the buildings sat still, quiet and empty—falling into disrepair, awaiting destruction.

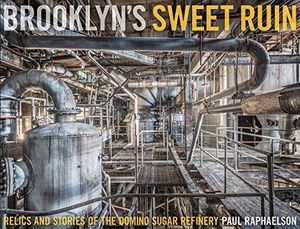

A year before demolition began clearing the way for new developments along the waterfront, photographer Paul Raphaelson documented the refinery’s remnants. Long fascinated by old factories and urban landscapes, he found in the buildings an intriguing subject: a type of Rorschach test because, he said in an interview, the factory “represents different things to so many different groups of people.” Raphaelson’s desire to explore how cities and societies relate to their symbols of modernity and progress—and what happens when they are outgrown and abandoned—drives his new photo book, Brooklyn’s Sweet Ruin: Relics and Stories of the Domino Sugary Refinery. Photographs from the book are also on display at New York’s Front Room Gallery until January 14.

Brooklyn’s Sweet Ruin: Relics and Stories of the Domino Sugar Refinery

Brooklyn’s Domino Sugar Refinery, once the largest in the world, shut down in 2004 after a long struggle. Paul Raphaelson, known internationally for his formally intricate urban landscape photographs, was given access to photograph every square foot of the refinery weeks before its demolition.

First built in 1855 by the Havemeyers, a wealthy, industrialist family, the refinery survived a fire in 1882, endured a couple changes in ownership, and underwent a rapid expansion, becoming the largest such complex in the world. Only 25 years after it opened, the factory refined more than half of the nation’s sugar. In 1900, the refinery was bought by Domino, a company whose iconic illuminated sign would later light up the Brooklyn skyline with a star dotting its “i.” The complex grew to occupy more than a quarter mile of Williamsburg’s waterfront and at its peak in the 1920s, the factory had the capacity to refine 4 million pounds of sugar daily and employed 4,500 workers. The thousands of employees, who made their living at the factory and lived in the areas surrounding it, cultivated the neighborhood’s early development and became an integral part of Williamsburg’s history.

Devoid of human figures, many of Raphaelson’s photos examine the once powerful, now dormant, machines used to refine the sugar. The processes ceased long ago but they scarred the building; walls are stained by rust and oxidized sugar, and the bottoms of massive bone char filters are streaked where the sugary syrup had dripped. From afar, some of the images become almost abstract and geometric: a bin distributor is reminiscent of a pipe organ; a view of staircases and railings blend together in an M.C. Escher-esque fashion.

But up close, Raphaelson reminds us that these objects once required knowledge—once specialized and useful—now irrelevant. “A thought lingered in the shadows between the machines: someone, not long ago, knew how to work these things,” he writes. Even though the factory is abandoned and those “someones” are long gone, details of former workers remain throughout: lockers plastered with 9/11 commemorative and American flag stickers and the occasional pin-up poster, a supervisor’s abandoned office strewn with paperwork and files, a machine with writing etched into its metal exterior.

By the time the factory shuttered in 2004, production and employee rolls had been falling for decades, as the company traded hands between various conglomerates and food producers’ increasing relied on cheaper corn sweeteners. Only a few years prior, refinery workers had staged the longest strike in New York City’s history: for more than 600 days, from 1999 to 2001, they protested treatment by Domino’s new parent company, Amstar. Despite the labor unrest, Domino had “became a kind of time capsule,” says Raphaelson. “The workers were in a place that was, for someone who had an industrial job, a utopian situation. They had, over the course of the 20th century, negotiated better and better worker contracts in terms of conditions and compensation.” But when the closure came, the workers, with so much specialized knowledge and no plans in place to be retrained, were abandoned like the factory itself.

One of the workers who was struggling to re-enter the workforce told The New York Times, “’I learned this past week that I’m a dinosaur… Having a job for a long time in one place is not necessarily a good thing. It used to mean I was reliable.” A decade later, another former employee shared with The Atlantic the pain he’d witnessed since the factory shut: “when the refinery closed some men lost their jobs, they had a pension but they became alcoholics because their wives left them, their kids had to drop out of college. If you’ve never been down and have to scuffle and scrape you don’t know how to survive.”

Artists have drawn on ruins for their work for centuries. As Raphaelson explains, the Renaissance movement used ruins to symbolize the conquest of Christianity over paganism, while Neoclassicsts found inspiration in Roman ruins and Romanticists focused on what happens when nature overtakes architecture.

More recently, the genre gained renewed attention, as well as criticism and the derogatory label “ruin porn” when photographers starting flocking to post industrial cities, most notably Detroit, to document urban decay. The artists, many of whom were privileged outsiders, received criticism for “aestheticizing suffering, while keeping aloof from the ruins’ history and the people directly affected,” says Raphaelson. “The work ends up devoid “any sense of just how life was going on and what this all meant to the people who were there; what the history was and how much suffering it all represented.”

There is danger in the intoxicating nostalgia that ignores or lessens the history surrounding decay, and it’s something that ruin artists must grapple with. The solution, Raphaelson argues, is contextualizing and working through the history. Alongside his 50-odd photographs of Domino’s ruins are an essay, an historical overview, and a smattering of interviews with former workers. That way, he says, “we can see beauty and historical horror; we can see timeless symbol and allegorical decay, all at once.”

Ruin photography often relies, to varying degrees of success, on emptiness to tell the story of a place and people. In 2014, months after Raphaelson photographed the buildings and before they were torn down, African-American artist Kara Walker challenged this vacuum, by bringing the history of the sugar industry and the human cost of capitalism into the Domino refinery.

Her piece, “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby,” was a massive installation: a 35-foot tall, sensualized Sphinx-like black woman sculpted out of white sugar and placed in the former raw sugar warehouse of the refinery, surrounded by small statues of serving boys coated in molasses. Nato Thompson of Creative Time, the arts organization that presented the project, wrote, “Walker’s gigantic temporary sugar-sculpture speaks of power, race, bodies, women, sexuality, slavery, sugar refining, sugar consumption, wealth inequity, and industrial might that uses the human body to get what it needs no matter the cost to life and limb. Looming over a plant whose entire history was one of sweetening tastes and aggregating wealth, of refining sweetness from dark to white, she stands mute, a riddle so wrapped up in the history of power and its sensual appeal that one can only stare stupefied, unable to answer.”

All of the Domino complex buildings, save for the main refinery which is slated to become office space, were demolished in 2014 by Two Trees Management, a real estate development firm. Designated a landmark in 2007, the sole-surviving building, which used to dwarf all the others, will soon find itself in the shadows of new high-rises, some towering 400 feet tall.

The Domino factory itself is just one part of the larger battle for development: building and demolition permits were issued so rapidly that in 2007, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named the East River waterfront to its “Endangered” list. And as the long-term residents have been pushed out over the past decade, Williamsburg and its neighboring Greenpoint have almost become metonyms for gentrification: the area saw the highest increase in rent average from 1990 to 2014 in all of New York.

Wary of waxing nostalgic, Raphaelson isn’t mourning the refinery per se, but he does reflect on what opportunities have been lost in its destruction. “I don’t necessarily think we need to have refineries on the waterfront, but I do think it’s a healthier city when people, like [former] refinery employees can live in that neighborhood if they want to, or not too far away,” he explains.

Because of the unionized wages, many Domino workers were able to afford housing in the surrounding neighborhoods but, since the refinery’s closing, they’ve been pushed out by rising rents. While the developers have agreed to provide some low-income housing in the new development, a lottery for the first redeveloped building had 87,000 applicants for the 104 affordable units. These fractions of availability offer little relief to the growing number of New Yorkers who, after being priced out of apartments, have been pushed to the city’s far edges.

More than a decade after the last workers left the refinery, hundreds of new residents and employees will flock to a commercial and residential complex (one building is open so far and the others are slated over the next few years). On the same waterfront, where a monument to both modernity and obsolescence once stood, a monument to gentrification rises in its place. At the top, the famous Domino sign, a relic of its past life and a continuing cultural marker, will alight again.