Cedric Walker grew up in Baltimore, but moved to Tuskegee, Alabama, in 1971 at age 18 to become a music promoter and stage manager, and later toured with the funk and soul band The Commodores. “I was with them when we were getting $300 a job, and we were building and struggling,” Walker says. “I learned discipline and much more in those early years, which set me on the trajectory of seeking excellence in live entertainment.” But in 1994 Walker gave up the music business and founded a circus.

Veronica Blair grew up in San Francisco, where she loved watching traveling circuses like the Pickle Family Circus, which performed for free in the nearby city parks. In 1998 at age 14, Blair joined the Make*A*Circus teen apprentice program and later studied at both the San Francisco School for Circus Arts—now the Circus Center in San Francisco—and the San Francisco Youth Circus. “I learned Chinese acrobatics from Master Yu Li, and I also studied aerials,” she says. “If you finished the program and wanted to make some money, you could go on tour.”

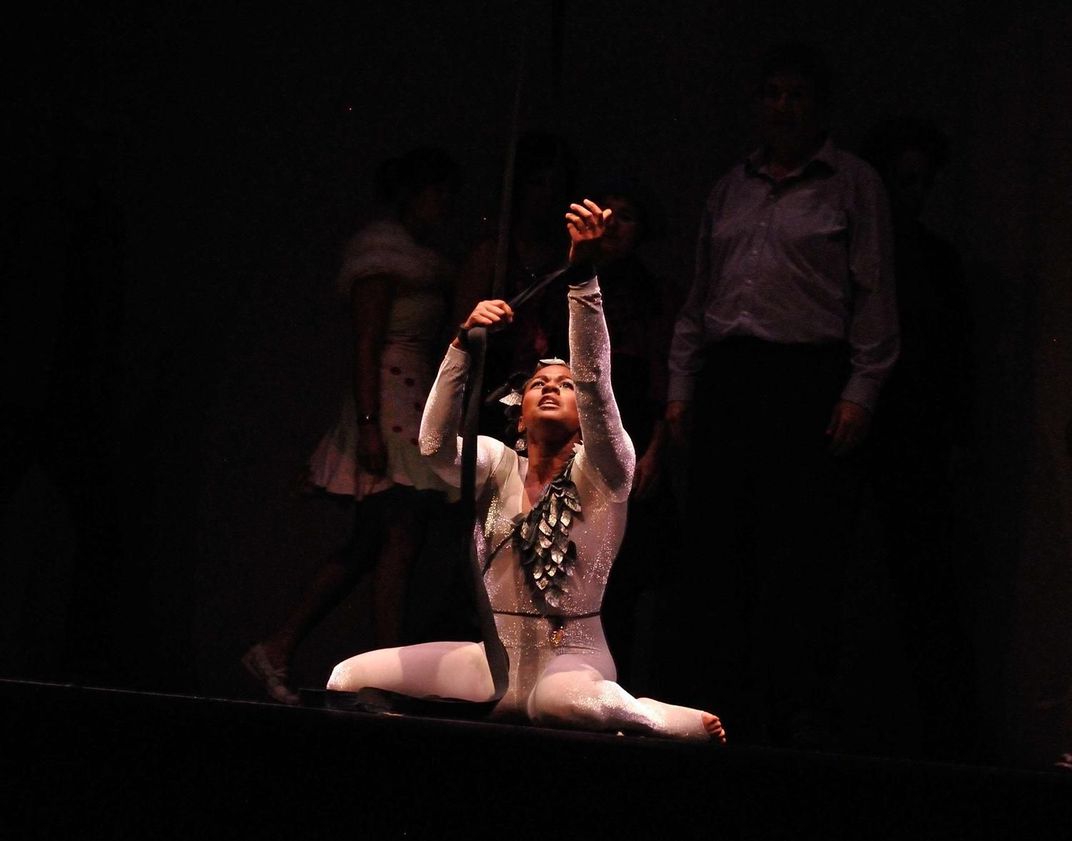

The career paths of Walker and Blair intersected when Blair joined Walker’s UniverSoul Circus in 2001 and for the next five years amazed audiences as one of the resident aerialists. Their paths will again cross at this year’s Smithsonian Folklife Festival, when both will be among the 500-plus participants—including acrobats, aerialists, clowns, cooks, equilibrists (or tightrope walkers), musicians, object manipulators (or jugglers) and riggers—in the Circus Arts program on the National Mall, starting June 29.

Walker and Blair also share a common fascination for the history of African-American circus. “I started studying black entertainment from the turn of the 20th century, and visited the Ringling Circus Museum in Sarasota, Florida,” Walker recalls.

Though not a circus performer himself, Walker sees potential in how the circus arts helps to promote cultural achievements and contributions of African-Americans. “We absorbed ourselves in the museum; we outlined the blending and merging of circus arts with African-American history, including music, dance, sports and much more.” Soon after his visit to the museum, Walker and his team founded UniverSoul Circus to promote and support inner-city communities. Walker explained, “UniverSoul is my way of combining the universe–by which I mean the global unity of people—with the soul—by which I mean the energy that moves us from within, that makes us laugh, that provides the color and the vibrancy of life.”

As UniverSoul’s resident aerialist, Blair learned of circus legend Emanuel Ruffin. Known as Junior, Ruffin was not only one of the foremost trainers of circus animals—lions, tigers, elephants, and more—but also a master of circus logistics while heading the transportation department for Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey’s Blue Unit. “I had met him a few times when he was elderly,” Blair noted, “but I had no idea about his significance until after he passed in 2010. Then I started to do my research, and learned how he was trained, how he came up through the circus, and how he was helpful in getting UniverSoul started, which had direct links to me.” Realizing that there was a dearth of information on African-American circus performers, Blair, who is currently with Circus Center in San Francisco, expanded her research and created the Uncle Junior Project, which includes a documentary film as well as oral histories collected from circus performers like aerial artist Susan Voyticky and Paris, the hip hop juggler, so that their lives and achievements will not be forgotten.

The Smithsonian’s Circus Arts program comes at an important moment in U.S. circus history, with the closing last month of Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey. Although many smaller circus companies are thriving, both Walker and Blair regret the loss of Ringling. As Walker explains, “Circus is a family, and we’ve lost a part of our family. Losing a part of Ringling is losing a part of ourselves. It is a great loss to all of us in the circus and around the world.”

In part because Blair was mentored by Pa’Mela Hernandez, the first African-American aerialist to perform with Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey, she sees Ringling’s departure as emblematic of a larger contemporary phenomenon. Having recently returned to the United States after eighteen months of studying circus arts in Japan, she observes, “America is not really a land of tradition. Unlike the Japanese, we are still trying to figure out who we are.”

“Circus is one of those things we will always have; it is like baseball, and will not ever completely disappear. But what we are losing are the circus traditions, especially as circus companies become more monetized,” she says. “As a performer now, you have to have an Instagram page, a YouTube page, a circus hashtag, and a thousand ‘likes.’ Circus is being Instagrammed, which helps to appeal to a larger audience, but it is losing its traditions.”

Visitors will explore not only historic circus traditions, but also many of the new expressions that reflect the changing social and cultural mores in the 21st century as part of the Circus Arts program at this year’s Smithsonian Folklife Festival, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this summer. Festival activities are free and open to the public on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., from June 29 through July 4 and from July 6 through July 9.