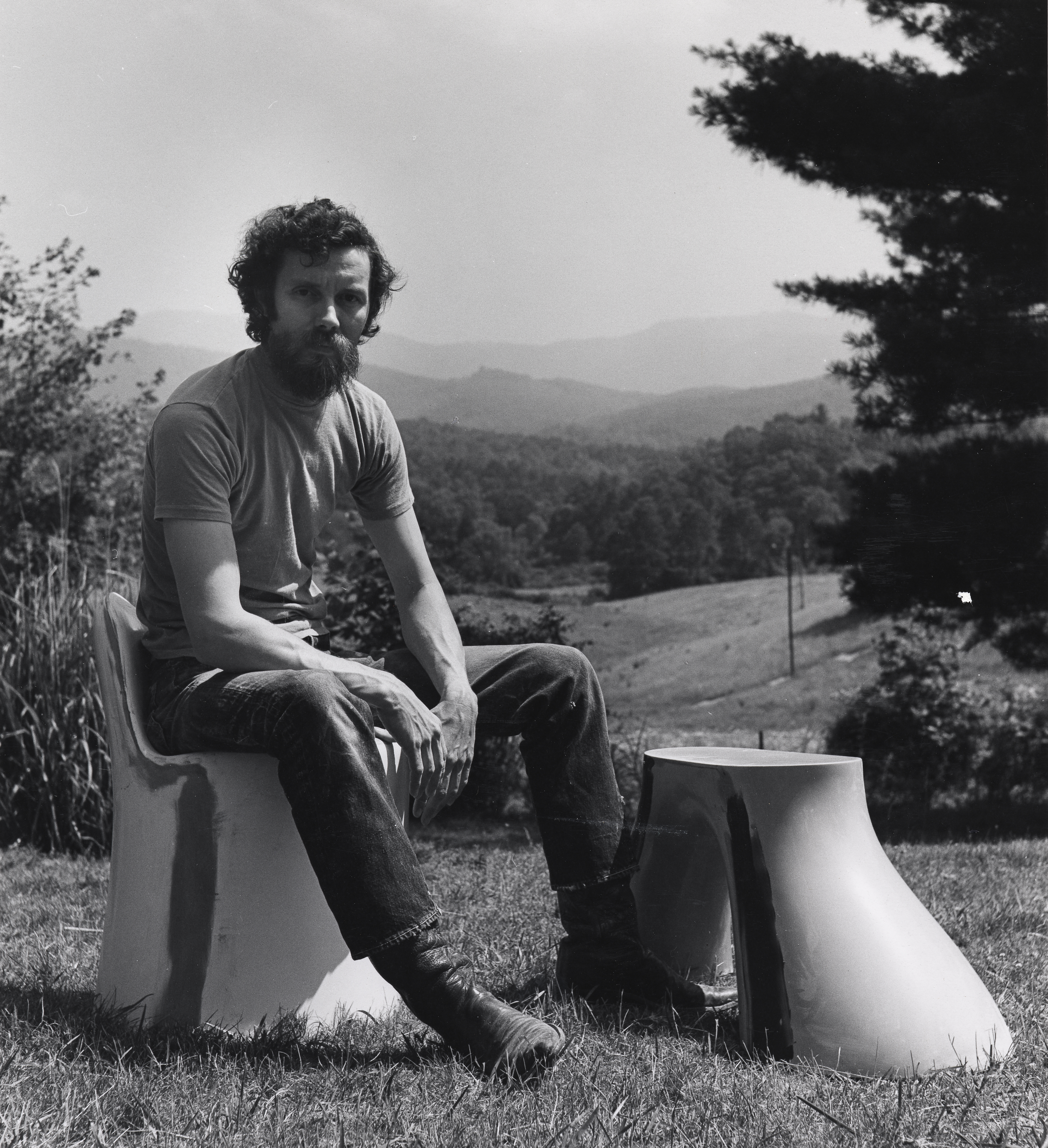

Wendell Castle—artist, craftsman, and educator—once explained that while form is paramount, “the function must be there. . . . A chair which is beautiful but cannot be sat in is nothing.”

As Castle told Newsweek in 1968, “I’m trying to get furniture off its legs and to be itself.” The furniture maker who once appeared on To Tell the Truth, and would go on to become a giant of the craft and design world, passed away on January 20 at age 85.

Smithsonian visitors familiar with the collections on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery likely have encountered Ghost Clock. The 1985 artwork has proven to be one of Castle’s most endearing and popular works. While a trompe l’oeil cloth—meaning to “fool the eye”—draped over a sculpture which is merely clock-shaped, does not find the counterbalance of form and function that enlivens so much of Castle’s furniture design, it does support evidence of his expert craftsmanship.

The ephemera of artists often have delightful stories to tell and as a reference archivist working in the collections of the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, I followed a trail rich with documentation showing Castle’s contributions to craft, including his own papers, the gallery records of two of his dealers Lee Nordness and Barbara Fendrick, two oral history interviews conducted in 1981 and 2012 and several letters.

One of them was from Mrs. Margo Mueller, who happened to catch Castle’s appearance in 1966 on television. In a note addressed “Dear Sir,” she wrote:

“On one of the daytime programs of ‘To Tell The Truth’ a man appeared who made furniture out of pieces of wood. He took whole hunks of trees to create his work. I believe he was a former sculptor,” wrote Mueller, before continuing to inquire about the three pieces shown on the air—a lamp, a desk and chair set, and a chest of drawers—and “any information you could supply concerning this gentleman, as I have forgotten his name.”

Castle’s appearance on “To Tell the Truth,” occurred the same year he was featured in LIFE magazine and also when he became acquainted with Nordness who contacted him about designing living room furniture for his apartment.

“I am just mad about your furniture, feeling that your handsome pieces are as much sculpture as furniture,” he wrote. Nordness came to represent Castle in his gallery and in 1968, gave him a one-man show at his gallery. It was not Castle’s first solo exhibition, but Nordness marketed the event to CUE magazine and House and Garden as the first showing for an artist-craftsman in a “fine arts gallery.”

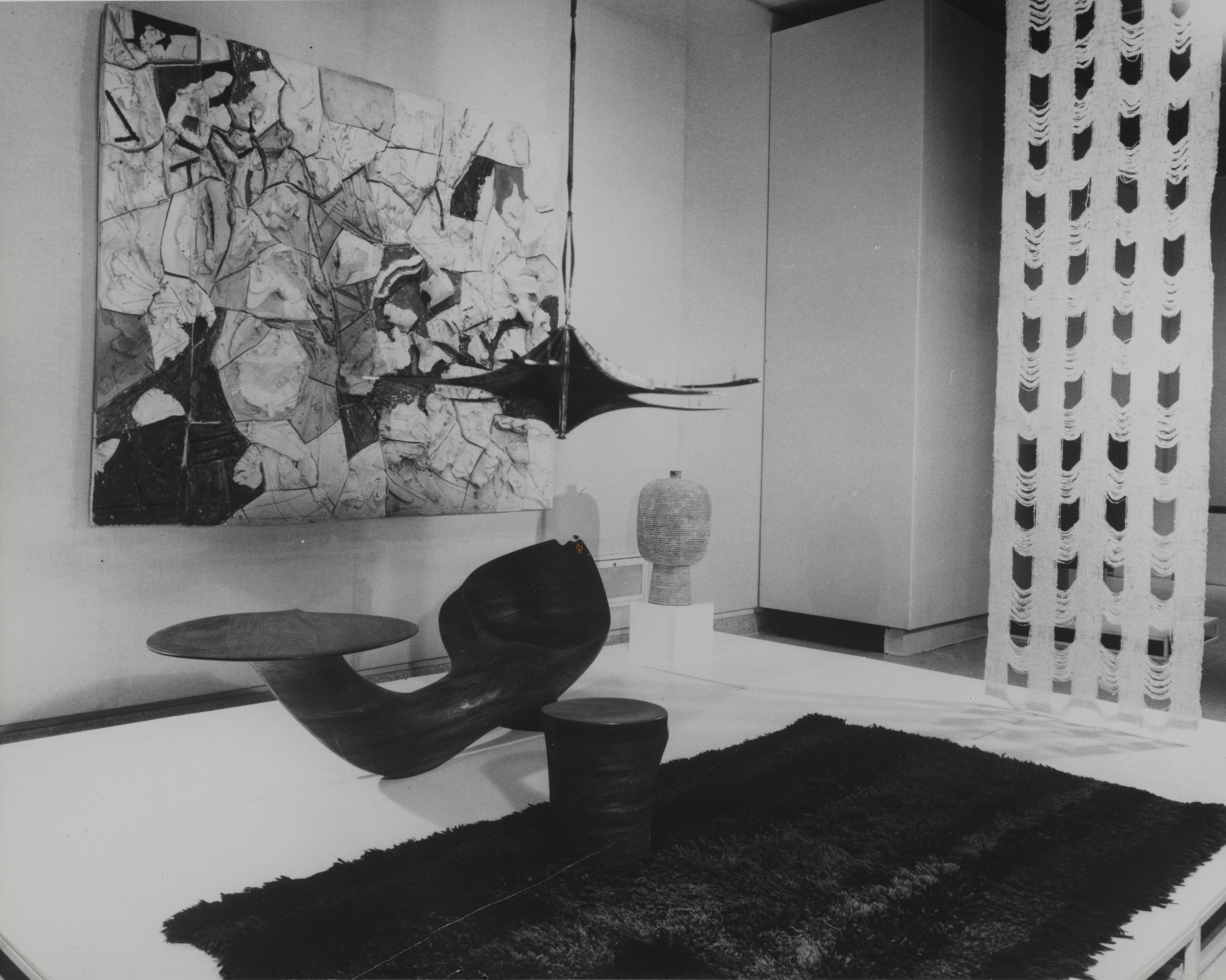

The idea of elevating craft into the realm of fine art, was one Nordness was committed to and explored in the seminal exhibition “Objects: USA,” which he organized with Paul J. Smith, the director of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Art and Design) acting as an advisor.

The show opened in 1969 at the National Collection of Fine Arts, known today as the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and travelled throughout the United States and internationally, under the sponsorship of the Johnson Wax Company until 1974. The exhibition featured 308 objects by more than 200 artists including Anni Albers, Robert Arneson, Lenore Tawney, Peter Voulkos, Dale Chihuly, Brent Kingston, Clayton Bailey, Ruth Duckworth and Lenore Tawney.

Meryl Seacrest noted in the Washington Post that the organizers “hope to show that the line traditionally dividing crafts from the realm of art is getting finer and at times may disappear altogether.” In the “Wood” section alongside Wharton Esherick, Sam Maloof and George Nakashima, among others, Wendell Castle had two pieces, Table-Chair-Stool (1968) and a mahogany and silver leaf piece, Desk (1968). A third piece Table (1969), made of laminated plastic, was in the “Plastic” section.

Castle’s process involved gluing and clamping one-inch layers of wood together to create large sculptural blocks that he then, as Gloria Dunlap notes, “carved away to create his furniture, rather than using more traditional methods of furniture making that involved adding rather than taking away.” He created a wide variety of forms in his work—sometimes bulbous, sinewy or serpentine, but always balanced.

Even a chair with three legs tapering down into graceful points, or his Stool from 1963, which has four thin legs that at the same time buckle inward and splay outward like a newborn foal, are at once delicate and sturdy. A 1989 headline in the Detroit Free Press declared him to be “The man who makes furniture dance.”

Along with experimenting with form, Castle imbued his work with a sense of playfulness. In particular, his Molar Chair of 1969, part of a series of brightly colored laminated plastic furniture with curves resembling teeth. And, his trompe l’oeil works, first exhibited in 1981 at Alexander F. Milliken, Inc. On the piece Table with Gloves and Keys, from that show, Joseph Giovannini writes,

But the gloves were more than an illusion. It seemed that Castle was throwing down the gauntlet, declaring that this table, which otherwise looked very much like an heirloom console was not a table: the gloves and keys made the piece nonfunctional, or at best only partly functional. What seemed to be furniture was, in fact, a work of art. What had promised to be a show of craftsmanship turned out to be an art exhibition.

Castle’s shows sometimes had “punny” titles: “Rockin’” a show made up primarily of chairs, and “Wendell Castle: About Time” which explored his clock designs. His interest in clocks grew out of a desire not to be seen solely as a furniture designer, but his notion, expressed in an interview for the “About Time” catalog: “there [is] one piece of furniture that’s more like a sculpture than any other—a tall case clock. . . . You don’t sit on it, you don’t put anything in it, you don’t eat off of it, you don’t do any of the normal things that you do with furniture. You look at it. And in some sense that’s what you do with sculpture.”

During the mid-1980s Castle began producing clocks, often with evocative titles such as Ziggurat Clock, Jester Clock and Four Years Before Lunch Clock, which had an original poem by Edward Lucie-Smith carved into its back. (Lucie-Smith also produced a limited edition chapbook of eight short verses in 1986, “Poems for Clocks for Wendell Castell.”) One of his clock sculptures was not a working timepiece, but also marked an ending. As Castle told Jeannine Falino in his 2012 interview for the Archives,

MR. CASTLE: . . . But it was very shortly after that I met [Alexander] Milliken, so the first thing I had to show Milliken were the trompe l’oeil pieces.

And he mounted a show—almost the same show; I may have added a piece or two—and he sold them all. But at that point I decided I didn’t want to do that anymore because, you know, you’d figured out how to do it, and the part that’s most exciting to me is that drawing and discovering new shapes and new ideas and new things.

Well, there wasn’t any room for that. That was just going to be doing the same thing over again. And at that point I also had gotten interested in the clock series—

MS. FALINO: Yes.

MR. CASTLE: — about that same time, because I had an employee, Greg Bloomfield, who was this kind of like a mechanical guy. He knew how to make things that worked, like clocks. But then also at the same time I decided that I would do one last trompe l’oeil piece, and that would be the end of it, and that was the grandfather clock called the Ghost Clock.

Castle’s Ghost Clock is a haunting sculpture, cleverly shrouded, and fooling the eye. But one thing this enigmatic work makes clear is Wendell Castle’s enduring legacy as a craftsman and artist.