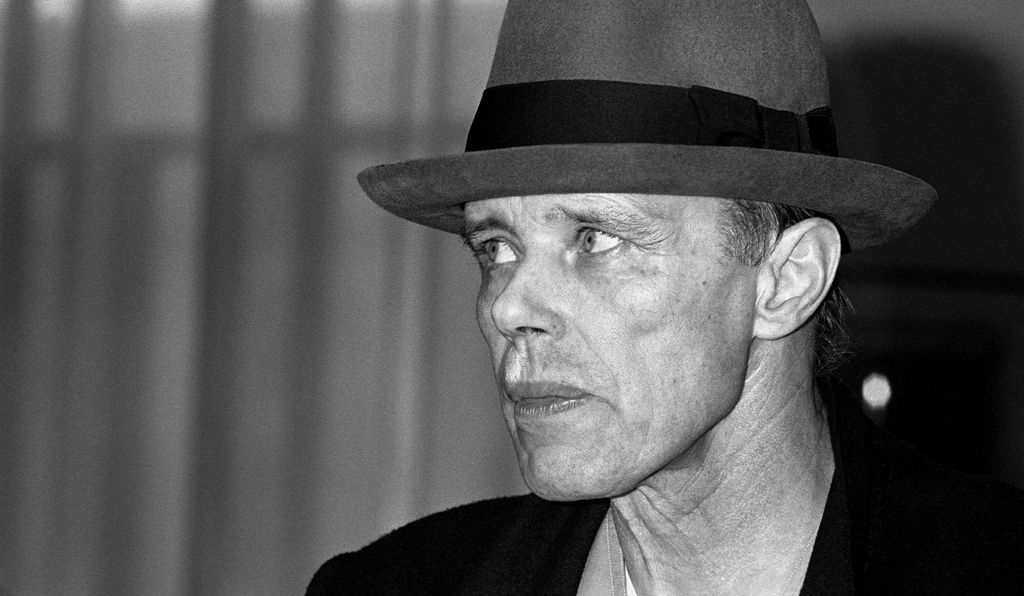

It was the summer of 1977, and the Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research was in full swing. As part of an art exhibition called Documenta, in what was then West Germany, the avant-garde artist Joseph Beuysled a series of public seminars and workshops on improving the future of society. An artwork in the discussion space set the unconventional tone: hundreds of gallons of honey oozing through an array of pumps and tubes, in a project Beuys likened to “the bloodstream of society.”

The topics included “Urban Decay and Institutionalization” and “Nuclear Energy and Alternatives,” with speakers from the worlds of science, history and politics as well as art. As the participants tossed around ideas, Beuys took notes and sketched diagrams on large blackboards. When the boards were full, he would erase them, then begin scribbling anew. Lecturing, listening, writing and erasing, he continued the sessions over 100 days. Afterward, he washed the blackboards clean.

Forty years later, two of those blackboards, along with a rag and the bucket Beuys used to clean them, are now part of the collections of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. The work is called F.I.U. Blackboards, after the Free International University, and according to Stéphane Aquin, chief curator at the Hirshhorn, the piece touches on Beuys’ deep dedication to teaching and to making society more inclusive, egalitarian and just. The work is “very much of the ’70s,” Aquin says—an era when, following on the cultural upheavals of the late 1960s, “society was understood by a whole generation as needing to be changed.”

Beuys saw art as an essential driver of that change. He envisioned art as “social sculpture”—a means to shape society, as classical sculptors shaped stone. “Every man is an artist,” he said, and only by channeling the creative work of all human beings could society be changed for the better. Beuys and other artists of his generation made a radical break from the abstract artists who came before them.

Artists, like the rest of us, read the news and wonder whether and how to respond. Many artists today reject the vision of their artwork as a means to improve society. So much has been tried already, and who knows if it’s helped. After all, as Aquin points out, Pablo Picasso’s anti-war meditation Guernica “didn’t do anything to Franco’s regime.” Instead, some artists separate their activism from their art, bolstering causes they believe in through volunteering and financial support. Andy Warhol could be a model here. “Warhol came across as the opposite of an activist,” Aquin says. “But he left $300 million in his will to support contemporary artists” and arts organizations. “He made sure there would be enough money for artists to continue thinking freely.”

Documenta, where Beuys made F.I.U. Blackboards, is an international art show that has been held in Germany about every five years since its founding in the 1950s. At its start, “it was dedicated to abstract painting, as a means to solve all the problems left by World War II,” Aquin says. Abstract art “was seen as a universal lingua franca that all men could understand—a way to look beyond the nationalisms” that had brought on the cataclysm.

But by the late 1960s, it was clear that, lingua franca or no, abstract art hadn’t transformed society, and Beuys and his peers began demanding a new role for art in social change. Aquin says, “These were people who thought, ‘You will not solve history with abstract painting. You will have to look elsewhere.’”

Beuys most certainly did look elsewhere, and long before 1977 he had been stirring up controversy with performance pieces—he called them “actions”—that thrilled some critics and appalled others. In one, he spent three days in a New York art gallery alone with a live coyote; in another, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, he did just what the title described, for several hours. (One critic would dismiss his ideas about art, science and politics as “simple-minded utopian drivel lacking elementary political and educational practicality.”)

The founding of the Free International University was itself a kind of “action,” and a further step on the artist’s path toward overt political activism. Beuys, a charismatic teacher and a natural disrupter, had taught at the State Art Academy in Düsseldorf during the 1960s, but he was dismissed in 1972 for, among other things, protesting the academy’s selective admissions policy. He argued that education was a human right and that the school should be open to all.

Fired but hardly silenced, he kept on teaching, attracting students with his magnetic personality and his sweeping vision of all that art should do. Under a manifesto he co-authored with the German writer Heinrich Böll, Beuys and a group of peers founded the F.I.U., a free-floating school-without-walls made up of intellectuals who believed in political, cultural and economic equality for all people. It rejected capitalism, institutional structures and the traditional teacher-student hierarchy, instead promoting wide-open discussions like those Beuys arranged at Documenta in 1977. The Free International University, Aquin says, “was quite a revolution itself.”

Beuys, who died in 1986, was an activist in work and in life, protesting inequality, environmental destruction and nuclear weapons. He was among the many founders of the German Green Party and even won a spot on a party ballot (although he withdrew before the election). He represents one model of activist art, Aquin says. “His main legacy is to have us think of art as social sculpture: Art is not just responding to history in the making, it is shaping history. It gives possibility to other ways of being.”

A second aspect of Beuys’ model of activism, he adds, is that as a charismatic artist, teacher and mythmaker, Beuys was a “party leader/guru kind of figure” with an avid following among artists and supporters, who helped manage his projects and spread his influence around the world.

Still, Beuys is hardly the only model of artistic activism. In Guernica, Picasso’s response to the 1937 bombing of a Spanish village by supporters of the fascist general Francisco Franco, bears witness to the horrors of war. The work, which may be the best-known piece of antiwar art of all time, is a completely different approach to political engagement from Beuys’. “Picasso is in his studio by himself, painting Guernica,” says Aquin. “It is a great statement. But he doesn’t have a following, he doesn’t establish teaching institutions, he is not in a didactic role.” He adds, “Sometimes an artist is just testifying, saying ‘This is what I see.’ It’s a response. It’s not always saying, ‘We have to do away with the system in place.’”

Other artists, though, continue to address social issues very pointedly in their work. Cameron Rowland, for example, “looks into systems of abuse of the African-American population in America,” Aquin says, such as the ongoing use of forced labor among prison inmates, a century and a half after slavery’s abolition. His works include captions that spell out in rigorous detail the links between the incarceration of African-American men after the Civil War, chain gangs and inmate labor today. He declines to sell much of his artwork. Aquin says, “You can’t buy his work. You can rent it. [He is saying,] ‘No, I’ll keep the power to myself.’. . . He is taking [up] arms against a whole system.”

Which brings us back to Joseph Beuys and those blackboards. At first glance, they are empty. A blank slate. There’s nothing there. But look at them for a while, and they start to ask questions. What was written there 40 years ago, written and then erased? What happened to all those ideas for the improvement of society? Did any of them take root? Is the world a better place?

And: What idea should we try next?

F.I.U. Blackboards is on view at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden as part of the exhibition “What Absence Is Made Of” through summer 2019.