On a bright blue sea beneath a bright blue sky he jumps. On his water skis and in his leather jacket he rises. He flies. Forty years later he’s flying still. That was Fonzie’s leap into legend and language when he jumped the shark on “Happy Days” in September 1977.

A ’70s sitcom about life in the ’50s, the show’s title was at once literal and ironic, an incantation of better times. To its fans the program was a simple pleasure in a complicated age. It premiered the year Richard Nixon was swamped by Watergate and resigned. The show took a few chances with social issues, matters of race or class or character, but just as often it was a wisenheimer’s sendup of anodyne 1950s sitcoms like “The Donna Reed Show” or “Leave It to Beaver.”

Charming and largely harmless, “Happy Days” somehow thrived in the great moment of subversive television satire, when “All in the Family” and “M*A*S*H” were both runaway hits and prime-time indictments of American cupidity.

My Happy Days in Hollywood: A Memoir

In My Happy Days in Hollywood, Marshall takes us on a journey from his stickball-playing days in the Bronx to his time at the helm of some of the most popular television series and movies of all time.

“Happy Days” was also incredibly popular in an era of mass entertainment, breaking into television’s Top 10 ratings before streaming or bingeing or even the splintering effects of cable. American audiences routinely measured in the scores of millions, compared with today’s niche programming. (For the avidly anticipated Series 7 premiere of “Game of Thrones,” 10.1 million viewers tuned in, setting a record for HBO. )

It is a measure of how wide and deep the show reached that Fonzie’s jacket entered the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in 1980, while the series was still on the air.

At the museum, the jacket is cataloged in serviceable prose: “From the Western Costume Company, measures overall: 25 x 19 in.; 63.5 x 48.26 cm, brown leather with brown knit cuffs and bottom; zipper closure; slash pockets on front; brown satin lining.” But NMAH curator Eric Jentsch invokes its poetry. “Fonzie was a representation of cool at a time when you were learning about what cool was.” Correctamundo. That popped leather collar! That pompadour! Ayyyy! Arthur Fonzarelli was a hoodlum with a heart of gold on a 1949 Triumph Trophy TR5 Scrambler Custom. And bomber or biker or cowboy, from the Beatles to the Ramones, from Brando to Mad Max to Indiana Jones, the leather jacket has never run low on cool.

So the jacket is the jacket, ineffable, a pinned moment on the American timeline, but the complexity and wit and energy expressed by the phrase “jump the shark” was then and is now a living, breathing thing, a big idea in three small syllables. It means to have passed the peak moment of your greatness, and through some absurd act, some bad choice, begun your inevitable decline. That the phrase persists is a tribute to the vigor and dynamism of colloquial American English and clear, uncluttered language; to the perfections of brevity; to the power of metaphor; to the beauty of slang, which lies not only in its artistry but in its utility.

Said to have been coined, at least in one account, at a late-night college bull session at the University of Michigan in 1985 by undergraduate Sean Connolly, “jump the shark” was later popularized by his roommate, comedy writer and radio host Jon Hein. But its well-worn origin story is less important than its persistence or its aptness or its uncanny economy.

According to Ben Yagoda, author of When You Catch an Adjective, Kill It: The Parts of Speech, for Better and/or Worse and connoisseur of vernacular American English, the phrase “identifies this phenomenon and sort of nails the case by naming it in this very vivid, funny, specific way.”

Fred Fox Jr., the writer of the episode, famously maintains that “Happy Days” did not jump the shark that night. “If this was really the beginning of a downward spiral, why did the show stay on the air for six more seasons and shoot an additional 164 episodes? Why did we rank among the Top 25 in five of those six seasons? That’s why, when I first heard the phrase and found out what it meant, I was incredulous.”

To this day it follows Henry Winkler everywhere. Forty years an actor and author and activist, fly fisherman and photographer, producer and director—he remains The Fonz. “When did I first hear it? I’m not sure. But it never annoyed me, because we were still a hit. We continued to be a hit for years to come. It is part of the legacy of ‘Happy Days.’ People say it to me all the time. I just caught this gigantic trout in Wyoming, I put it on Twitter, and someone said, ‘Look at that—you just jumped the trout.’”

If we’re lucky, it’s a jump we all make, the long arc across the years, from youth and daring into uncertainty and old age, in brief defiance of logic and gravity.

In the end, it is a leap of faith. And the shark, after all, is insatiable.

So now and forever, we jump.

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $12

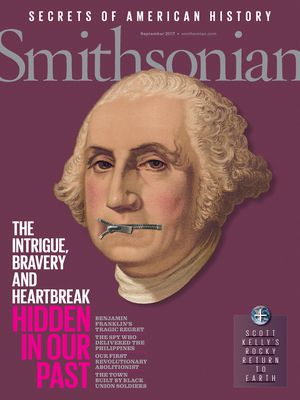

This article is a selection from the September issue of Smithsonian magazine