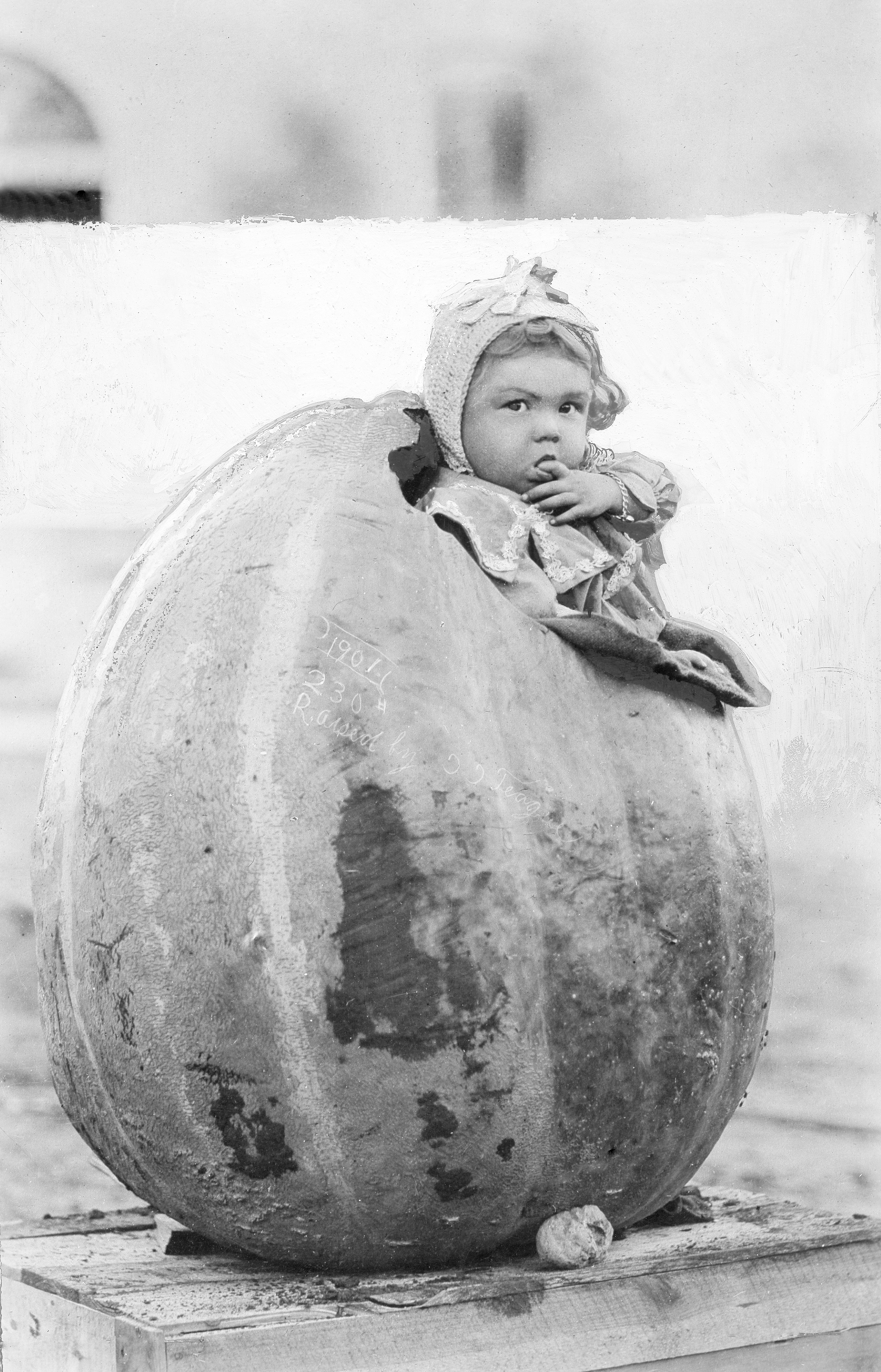

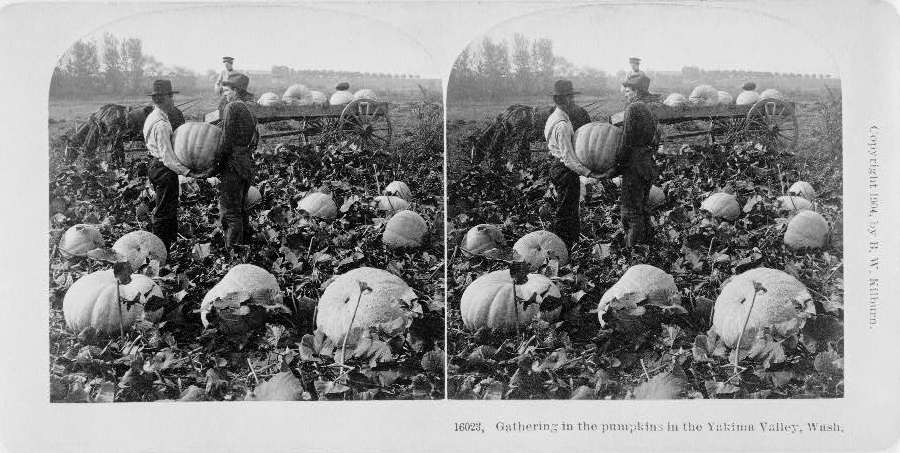

Belgium is supposed to specialize in Brussels sprouts, but last autumn a horticulturist there raised a 2,624.6-pound pumpkin, squashing the world record for the heaviest fruit. American growers were dismayed. Pumpkins, after all, are indigenous to the New World. The first European settlers were stunned by the Native Americans’ ample squash crop, which they mistook for melon. Centuries later, pumpkins so impressed newly arrived Irish immigrants that they abandoned the turnips they’d carved into jack-o’-lanterns for All Hallows’ Eve back home. And pumpkins became an American Halloween doorstep classic.

Yet for two out of the last three years, the world’s largest pumpkins have sprung up in Europe. “They’re doing very well, and I tip my hat to them,” says Ron Wallace, a country club manager in Greene, Rhode Island, who was paraded on the shoulders of jubilant pumpkin growers one glorious day in 2006 after his squash became the world’s first to break 1,500 pounds. Today, pumpkin growers are gaining on 3,000 pounds, but the Belgians, Swiss and British are in the lead.

While other fruits and vegetables may flourish in warm climates, the record-setting pumpkins—a variety of Cucurbita maxima bred in Nova Scotia—actually prefer cooler weather. New England has long been considered an ideal environment for them. “We get warm but not too warm, cool but not too cool,” explains Matt DeBacco of Rocky Hill, Connecticut. Summer days are in the mid-80s, maximizing photosynthesis without desiccating the bloated fruit, and the semi-northerly locale means bonus sunlight hours throughout the growing season. By June the burgeoning giants are growing at an exponential rate, and by August, they’re packing on one to two pounds per hour, while guzzling about 100 gallons of water every day.

In addition to gentle sunshine, the Northeast specializes in Yankee ingenuity. Nearly all the giant pumpkins in America are grown by amateur gardeners who toil in backyards after work, hardened by hailstorms and hungry woodchucks. “Some of these guys will try anything!” says Steve Reiners, a horticulture professor and commercial pumpkin specialist at Cornell University. They are almost fiendishly inventive—for instance, designing their own snowshoe-like footwear that won’t crush the soil, or spiking the stingy local dirt with fertilizers and fungi to maximize a pumpkin’s water and nutrient absorption.

Many growers keep online pumpkin diaries, so there is plenty of cross-pollination. Still, the hobby is full of closely gourded secrets. High-performance pumpkins like the Pleasure Dome and the Freak II have left lasting genetic legacies, and individual seeds of the sort you might ordinarily salt and crunch by the handful have sold at auction for as much as $1,781.

European giant pumpkin contests first took root around 2000, just about the time a prominent American giant pumpkin grower was assigned to a U.S. Army base in Germany. The arrival of his orange thumb, notes Jan Molter, treasurer of the European Giant Vegetable Growers Association, coincided with a burgeoning European interest in American-style Halloween. (Yes, the giant pumpkins, with their foot-thick walls, can be carved, ideally with a chain saw. They also make excellent boats.) The first German gourd-baking championship and pumpkin expo took place in 2001.

Europe’s subsequent rise has been defined by the controversy over indoor growing. The Old World’s big players cluster in Northern Europe, where the weather is often harsher than New England’s. However, high-tech greenhouses with heating and air-conditioning, irrigation systems, automatic fertilization and other frills allow growers to mimic, and in the last few seasons, maybe even improve upon a New England-like climate. There are no ravenous white-tailed deer in greenhouses, and it can be a perfect June afternoon in Vermont every day of the year.

And because not just anybody can have an industrial greenhouse, it just so happens that several recent overseas champs have been professional plant scientists. The 24-year-old Belgian winner, Mathias Willemijns, is the lead technician at a large vegetable research center, for example, and has his own personal 130-foot polytunnel, in which he grew just four pumpkins, each of which, by harvest time, tipped the scales at more than 2,000 pounds.

This autumn, the news from New England is not reassuring. The patches suffered through a cloudy spring, and in peak season the giants were barely gaining 30 pounds a day, compared with their typical 50. There is some griping about the affordability of European hydroelectric greenhouse heat in Europe, but spirits remain high. DeBacco believes salvation lies in soil nutrient nanotechnology and genetic technologies. Wallace has faith in the providence of New England weather. In the meantime, he’s encountered a keen new market for his signature giant pumpkin fertilizer, which is called Wallace Organic Wonder, or WOW. (“The cannabis growers have found me,” he says, “and they are very, very happy.”)

It’s raining during a visit to a suburban Connecticut backyard giant pumpkin patch. Despite the drizzle, the sprinkler sways over the rambling pumpkin vines nearby: A hundred gallons is a whole lot of water. From under his dripping hat, Steve Maydan beams down at his pumpkin, which he is thinking of calling the Creamsicle. The whole community is rooting for him. He points out where three of his neighbors cut down trees at the same time—to allow his garden more sunlight, he suspects. He shows how he slakes the thirst of a second, remotely located pumpkin patch by snaking a very long green garden hose through the neighborhood sewers.

Barring a miracle, the Creamsicle will weigh in at a relatively dinky 1,000 pounds, just a statewide finisher at best. But Maydan is getting wilier every year. His problem woodchuck has been vanquished at last, the powdery mildew hasn’t destroyed him yet, and he’s feeling…pumped.

A Brief History of Improbably Large Produce

In the madcap world of competitive horticulture, the pumpkin takes the prize, reaching the weight of a Ford Fiesta thanks to its sturdy shape, souped-up genes, bountiful sugars and nourishing root fungi. But in recent years even cabbage has been supersized. –Kyle Frischkorn

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $12

This article is a selection from the October issue of Smithsonian magazine