Before we get to the matters at hand—including the ways in which we humans judge one another and an energetic puppet with autism named Julia—let’s consider the current value of a piece of imaginary real estate known as Sesame Street. Since its launch in 1969, the show has often been kids’ first step into the world beyond their living room rugs, the common cultural campfire for 95 percent of preschoolers—about 200 million Americans—who watched the show as children.

And it is a place—an ingenious staging of reality. “Here, they created a street and a community that closely resembles what kids experience,” says Jeffrey D. Dunn, who arrived to run Sesame Workshop as CEO in 2014. “It’s not fantasy land, and it’s not a made-up, faraway place.” He pauses. “That’s one of the things that makes it so powerful.”

For years the show’s creators have been spicing up their alluring, hand-held curriculum of ABC’s and 1,2,3’s with lessons about life as it is. There has been standout content on marriage and death, on the families of those in the military, on hunger in America and kids with incarcerated parents, and there was an HIV-positive Muppet on the South African series.

But one of the most groundbreaking innovations in its long history of wondrous storytelling began in the late 1990s, when Leslie Kimmelman, then an editor at Sesame Magazine, noticed that she had company at work: other folks who had kids with autism. What was more, the characters that her colleagues crafted spoke powerfully to her son, Greg. At 3, he seemed to connect deeply to Sesame characters. “Mention Elmo, he’d turn to you,” she says. A naturally musical child, he watched episodes with glee, singing the songs. By age 5, he’d spent two Halloweens dressed like Elmo.

“There was a little cell of us,” she recalls. “Parents with kids on the spectrum, who knew how powerful the show’s effect was on our children.” Of course, they all thought about their kids someday seeing a reflection of themselves on the show. “And then other kids could see them, too? Wouldn’t that be something?”

Currently, one in every 68 children—and one in every 42 boys, or 2.9 percent of the male population—are on the autism spectrum. But autism is a diverse and divided continent. The spectrum stretches from what, in the 1940s, Hans Asperger first dubbed his “little professors”—chatty but socially obtuse children, intensely focused on some narrow interest—to kids with no speech who are often self-injurious, caught in sensory tsunamis. It’s also a battleground, with self-advocates asserting they’re just differently abled, not disabled, and others crying out for supports to live the most basic life.

How would it be possible to create a Sesame Street character that could bridge this span?

In 2010, Sesame began consulting with educators, psychologists and activists, and Sherrie Westin, Sesame Workshop’s executive vice president of global impact and philanthropy, decided to put resources into an autism initiative. Creative teams worked with experts. Staff visited clinics and schools. Kimmelman was assigned to write a storybook featuring an autistic character.

Although boys with autism or autism spectrum disorders, collectively termed ASD, outnumber girls about 4.5 to one, it was decided, after much debate, that the Sesame character would be a girl. (Sesame viewed the choice as more counterintuitive.) Kimmelman suggested the name Julia (after her older daughter, who’d been such a support to Greg). Julia it would be.

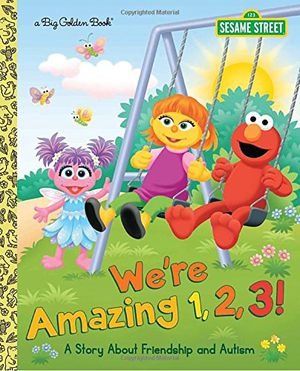

At first all a toddler sees is a giant yellow bird and a grouch in a trash can. But episode by episode, he or she realizes that Big Bird’s defining characteristic may not, in fact, be his conspicuous height or the hue of his feathers, any more than Oscar can be judged solely by his taste in condominiums. They are defined by an array of human traits, which young viewers somehow recognize with heightened clarity when expressed by puppets. Julia has autism, but she also has green eyes and red hair and an artistic temperament. Does autism define her? Isn’t the first thing we tend to notice about people whatever makes them different from us? Sesame’s autism initiative is about fighting this most harmful of human instincts. Its battle cry is “See Amazing in All Children.” Kimmelman’s picture book, We’re Amazing, 1,2,3, helped to introduce Julia to the world in 2015, and soon the board of Sesame Workshop determined that Julia had passed her audition. She’d be moving up to the show. Sesame’s longtime home, PBS, and its new joint home, HBO, decided to simulcast the episode.

What followed was months of work for the artists, writers, actors, puppeteers and others—work that often drew on their personal experience. The puppeteer, Stacey Gordon, has a son on the spectrum. The designer, Louis Mitchell, had volunteered at a school where he had befriended a girl with autism. The scriptwriter, Christine Ferraro, who has penned around 100 or so “Sesame Street” episodes, had a sibling on the spectrum, Steve, two years her senior.

A sibling sees things a parent doesn’t. They live in the same present tense as the affected individual. The parents eventually fade. The sib, in it for the full-life journey, is shaped by the brother or sister on the spectrum, and is often the only neuro-typical person an ASD person knows intimately, the one they turn to in distress. Or elation. Steve enjoyed ”Sesame Street” as a kid, then moved on to science fiction of all kinds, in all media. This is what folks on the spectrum generally do: make sense of the world through their passions. Asimov or Arthur C. Clarke or the real trouble with Tribbles—it’s what Christine and Steve shared, a place where he’d lead the game. “My experience with my brother informed my writing,” Christine says. “My goal was to help clarify and destigmatize autism for viewers.” After Christine had written the episode but before it aired, Steve died suddenly of a heart attack at 51.

When I met with Christine in the conference room at Sesame’s office, just across from Lincoln Center, she recounted how she and her parents went through his 5,000 VHS cassettes, none of them marked except the one she most wanted to see: Conan O’Brien, August 2005. She opens up her computer. The recording is now on her hard drive. “He was so proud of this.” In the segment, Conan’s “reporter” visits a sci-fi convention. And there’s Steve, wearing a “Dr. Who” scarf. He’s discussing the yearly cast changes in “Doctor Who” and the merits of “Battlestar Galactica.” The audience laughs. “Steve loved this tape. He didn’t realize they were mocking him. Or he didn’t care.”

In the show’s next segment, Conan ventures into the audience and greets a surprise guest in an aisle seat: Donald Trump. “Remarkable!” Christine laughs. Steve and Trump, on the same tape! Audience members laughed at Steve. They laugh with Trump. Two ways of looking at the world. Two ways of telling your story. One plays the role of winner. The other stands at the opposite pole, swathed in a muffler recalling a benevolent time traveler, Dr. Who, a seeker who conjured what he knows from what he found in the world. One man is destined for history’s largest stage. The other is, simply, amazing.

Julia made her on-air debut this past April, during Autism Awareness Month. Sesame’s brilliant ten-minute episode starts with Abby Cadabby, Elmo and Julia gathered at a table to paint, as Alan, who runs Hooper’s store, hands them art supplies. Big Bird sidles up, and says hi to Julia, who is deeply involved in her painting and doesn’t respond. Big Bird’s confused. Alan explains that she’s “just concentrating on her painting right now.” More entreaties follow, but there is no response. When Alan asks to see it, she holds up her painting, which is vivid and precise.

“Julia, you’re so creative!” Abby says. The episode skips along from there, as Alan soon explains to Big Bird that Julia “has autism, and she likes it when people know that.”

“Autism. What’s autism?”

“Well, for Julia, it means that she might not answer you right away…and she may not do what you expect. Yea, she does things just a little differently, in a Julia sort of way.”

Midway through the episode, Julia gets excited as the kids begin to play a game of tag. She, like many spectrum kids, begins to jump for joy as she joins in. “Looks like she’s playing tag, while jumping,” Alan says.

We’re Amazing 1,2,3! A Story About Friendship and Autism (Sesame Street) (Big Golden Book)

We’re Amazing 1,2,3! is the first Sesame Street storybook to focus on autism, which, according to the most recent US government survey, may, in some form, affect as many as one in forty-five children.

“I’ve never seen tag played like that,” says Big Bird. Alan explains that Julia does some things that for Big Bird “might seem confusing,” like the way she flaps her hands when she’s excited. Then, nodding to the kids, who’ve returned, he adds, “Julia also does some things that you might want to try.” Abby, Elmo and Julia bounce across Sesame Street, ecstatically playing Julia’s reinvention. “Look,” Abby cries, with joy. “It’s a whole new game. It’s boing-tag!”

Julia made her entrance to national fanfare. “My reaction was total excitement, the excitement of seeing a new life come into the world,” recalls Rose Jochum of the Autism Society of America. “For all the little kids who have autism, it’s validating to see characters like themselves on television, instead of feeling invisible.” Jochum connected to one scene in particular. “When Julia interacted with the character of Alan, he takes her upstairs when the noise of a passing police siren upsets her. Watching the two of them interact. That was special to see.” Julia’s artwork, too, was inspiring. “The picture she drew—the wonderful bunny with wings—I love that she might be a budding artist.”

The Georgetown Center for Child and Human Development, in a study of the impact of Sesame’s autism initiative’s website on two populations of parents—those with an ASD child, and those without—concluded that the site can help “reduce biases and stigma, increase acceptance and inclusion, and empower ASD children with knowledge and positive information about themselves,” according to Bruno Anthony, the center’s deputy director.

The most impressive evidence of Julia’s power came from people with autism, who saw something they’d never seen before: a reflection of themselves. Letters and emails flooded into Sesame from across America and around the world. Everyone, from Dunn on down, read and wept and cheered.

“I am a grown-up. But I am like you,” reads one email pulled from the tide, addressed directly to Julia. “I am scared of noises. I don’t like my hair to bother me. What I say doesn’t always make sense to other people.”

“I hope you like ‘Sesame Street,’” the writer continues. “I hope you meet lots of kind, good people there. I will watch you on TV. And maybe I will get to meet you some day…but only if that’s okay with you.”

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $12

This article is a selection from the December/January issue of Smithsonian magazine