At an early age, Jacob Lawrence knew something was missing from his education. “I’ve always been interested in history, but they never taught Negro history in the public schools. Sometimes they mentioned it in history clubs, but I never liked that way of presenting it. It was never studied seriously like regular subjects,” the prominent black artist once said.

It was this absence of black stories and black history—and his desire for them to be considered essential to understanding the American experience—that inspired his life’s work: from simple scenes to sweeping series, his art told the stories of everyday life in Harlem, stories of segregation in the South, and stories of liberation, resistance and resilience that were integral to African American and American history.

Lawrence was born in Atlantic City 100 years ago on September 7, 1917. Raised for a time in Philadelphia, he came of age in 1930s New York, heavily inspired by the cultural and artistic ethos of the Harlem Renaissance. A number of his works are among the collections of the Smithsonian’s museums.

At a time when the mainstream art world wasn’t open to black artists, Lawrence immersed himself in everything his neighborhood had to offer: he trained at the Harlem Art Workshop, studied under and shared a workspace with painter Charles Alston and was mentored, among others, by sculptor Augusta Savage, who helped him gain work through the WPA Federal Art Project.

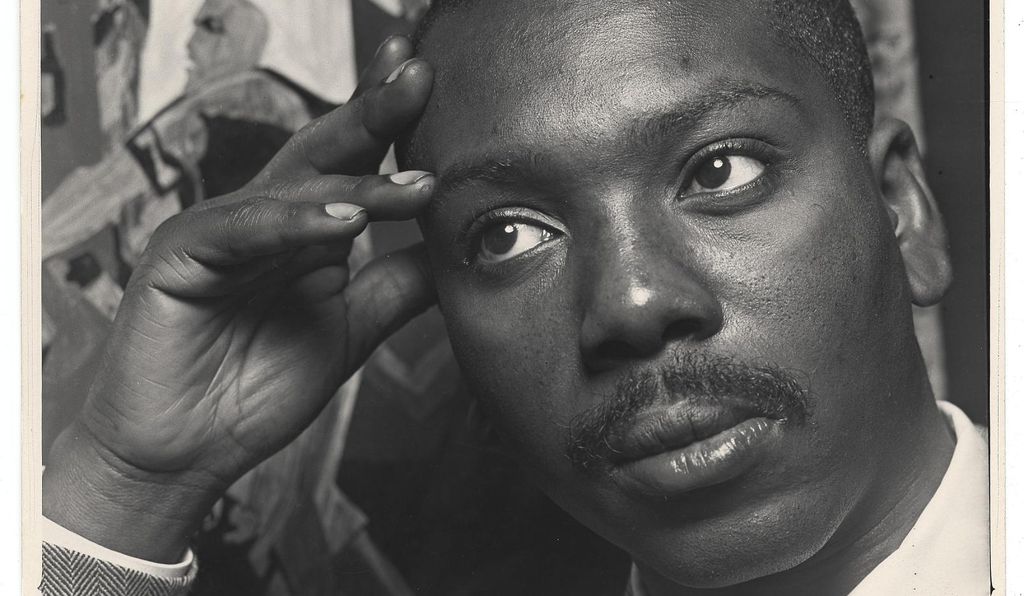

“He was a quiet individual who listened, looked, watched, absorbed all of what was going on around him,” according to Virginia Mecklenburg, chief curator at Smithsonian American Art Museum, home to nearly a dozen of Lawrence’s works.

Lawrence’s subjects and style were deliberate, conscientious choices. He formed his practice during a period when black artists were carefully considering their role and responsibility in depicting African American history and contemporary life.

In Harlem, Lawrence was surrounded and educated by progressive artists who “admired the historical rebels who had advocated revolutionary struggle to advance the cause of the oppressed,” writes art historian Patricia Hill in her book Painting Harlem Modern: The Art of Jacob Lawrence. From them, he was inspired to tell historical epics centered around major figures, all of whom have once been enslaved. His early series told the stories of Toussaint L’Ouverture (1938), who led the struggle for Haiti’s independence, Frederick Douglass (1939), the great abolitionist and statesman, and Harriet Tubman (completed 1940), the celebrated conductor of the Underground Railroad.

And how he told those stories mattered as much as choosing to tell them. Throughout his career, Lawrence painted with vibrant and bold colors and remained dedicated to an expressive figurative style, one that lent itself to visual narration. Jacquelyn Serwer, chief curator at National Museum of African American History and Culture, which features Lawrence’s Dixie Café (1948) in its exhibition “Visual Art and the American Experience,” says he wanted to make sure “that important aspects of African American history were documented in a way that could be appreciated and understood by a very broad audience.” If he adhered too closely to the modernist, abstract trends of the mid-20th century, he risked limiting those who could connect with his art. Certainly, “the commitment to figuration was a political one,” says Evelyn Hankins, senior curator at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, which counts Lawrence’s Vaudeville (1951) among its collections.

For his most renowned work, Lawrence turned to an event that had defined his own life. The son of parents who moved during the Great Migration—when millions of African Americans escaped the Jim Crow South to seek better lives in the North and West—he painted the stories he’d been told. Across 60 panels, he showed, and spelled out in the titles, the harsh racial injustice and economic difficulty African Americans faced in the South and the opportunities that brought them to places of greater hope.

The Phillips Memorial Gallery (now known as the Phillips Collection) and the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) purchased the Migration Series (1941) the year following its completion. While each museum took half of the series for their permanent collections—dividing it by even and odd numbered panels—the full series has been exhibited a number of times, most recently in 2016 at the Phillips Collection. Not only had Lawrence achieved a major personal success at 24, the sale was important for another reason: it marked the first time that MOMA had purchased artwork by an African American artist.

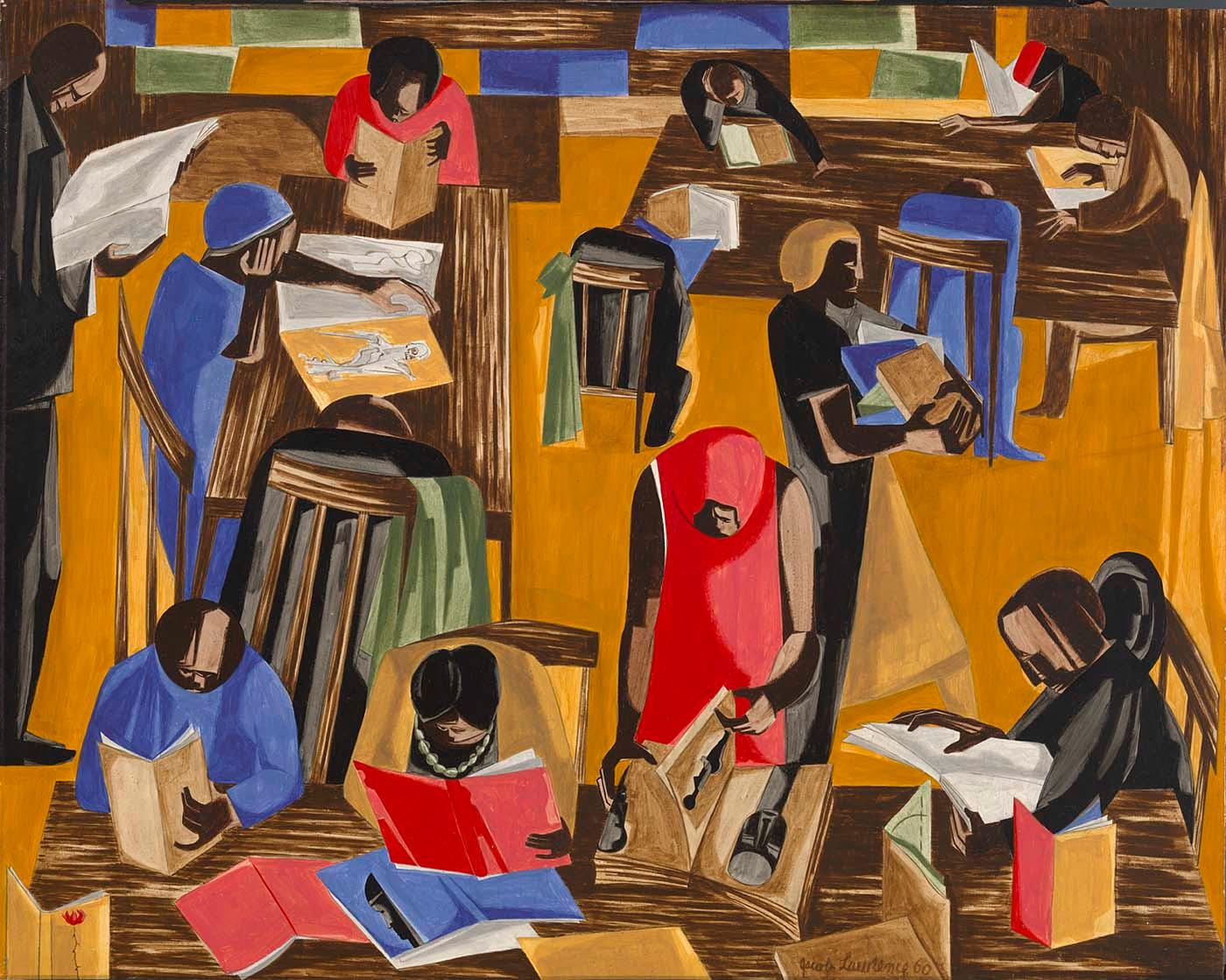

Much of his prodigious output was in genre paintings and in the portrayal of everyday scenes; he drew what he knew from his life in Harlem. One example, The Library (1960), depicts a few black figures reading books that reference African artwork. Curators speculate that the reading room “may show the 135th Street Library—now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture—where the country’s first significant collection of African American literature, history and prints opened in 1925.” It was at that library Lawrence spent hours researching his historical epics, poring over black history and heritage. In painting this scene, he spotlighted the discovery and learning catalyzed by the Harlem Renaissance.

If The Library offers a view of a comparative oasis in the North, a look at Lawrence’s Bar and Grill (1941) illustrates a sense of the stark reality in the South. The artist first visited the region when he and his wife, fellow artist Gwendolyn Knight, traveled to New Orleans in 1941. Although he’d depicted Jim Crow segregation in his Migration Series, the personal exposure to the harsh Southern laws left Lawrence shaken, and he went on to explore the experience in a number of works.

Emphasizing the artificial barrier between the two races, Bar and Grill puts in plain view the falsehood of separate but equal: the white customers are kept comfortable and cool on their side, attended to by the bartender, while the black patrons are relegated to a less spacious, overlooked section, emblematic of their second-class status in the South.

World War II again brought Lawrence in close contact with Southern racism: drafted into the Coast Guard in 1943, he trained in St. Augustine, Florida. He was later assigned to the Navy’s first integrated ship, where he was able to paint as part of his deployment.

Lawrence and Knight would later return to the South in 1946 where he taught a summer course at Black Mountain College, a liberal arts school in North Carolina. Invited there by the head instructor, German abstract artist Josef Albers, he and Gwendolyn steered clear of nearby Asheville, aware of the racism they might encounter there. On their journey down, Albers even reserved a private train car for the couple to avoid having to make the “humiliating move from integrated train cars to Jim Crow cars once they passed the Mason-Dixon Line.”

Having documented historic liberation struggles, Lawrence soon turned to explore the contemporary civil rights movement. As art historian Ellen Harkins Wheat wrote, “responding to this era of turmoil and antiwar upheaval. . . Lawrence produced a body of work that manifests his most overt social protest.” Involved in fundraising for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Lawrence painted scenes of counter sit-ins, freedom riders and protestors clashing with the police.

During his six decades as a practicing painter, Lawrence influenced a number of other artists. He began teaching at Pratt Institute in 1956 and, when the Lawrences lived in Nigeria in the early 60s, he offered workshops to young artists in Lagos. After stints teaching at the New School, Art Students League and Brandeis University, his final move was to Seattle in 1971 for a professorship at University of Washington. Lawrence’s celebrated career was filled with further milestones: he was a representative for the United States at 1956 Venice Biennale and he was awarded both the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal in 1970 and the National Medal of Arts in 1990. Until his death in 2000, he continued to paint and exhibit his work, even during a brief period spent in a psychiatric institution recovering from stress and exhaustion.

A century after his birth, his work remains relevant and resonant, thanks to his remarkable storytelling. “The human dimension in his art makes people who have no interest in art, or no experience with, or real knowledge of art, look at Lawrence’s work and. . . see stories that they could find in their own lives,” says Mecklenburg.